Women Avoid STEM Degrees to Get Better Grades?

Catherine Rampell at The Washington Post has "A message to the nation's women: Stop trying to be straight-A students."

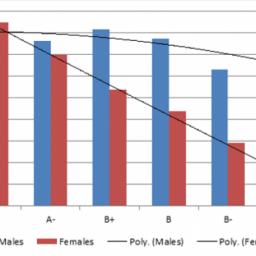

Catherine Rampell at The Washington Post has "A message to the nation's women: Stop trying to be straight-A students." In her analysis of others' findings, she writes of a discouragement gradient that pushes women out of harder college degrees, including economics and other STEM degrees. Men do not seem to have a similar discouragement gradient, so they stay in harder degree programs and ultimately earn more. Data suggests that women might also value high grades more than men do and sort themselves into fields where grading curves are more lenient.

"Maybe women just don't want to get things wrong," Goldin hypothesized. "They don't want to walk around being a B-minus student in something. They want to find something they can be an A student in. They want something where the professor will pat them on the back and say 'You're doing so well!'"Why are women in college moving away from harder degrees?

"Guys," she added, "don't seem to give two damns."