How Pronto can become a beautiful public bike system by going bigger

Bike share is beautiful. Bicycles owned by the public, available to the public at any time for just a couple bucks. It's a public bicycle transit system operating on a relatively shoestring budget. It's not a system designed with hardcore cyclists in mind, it's designed for everyone else.

Bike share is beautiful. Bicycles owned by the public, available to the public at any time for just a couple bucks. It's a public bicycle transit system operating on a relatively shoestring budget. It's not a system designed with hardcore cyclists in mind, it's designed for everyone else.

Or at least it should be. With so much of our coverage of Pronto focusing on problems with management and reasons ridership fell short of projections, let's look forward to what Pronto could be. Because while Seattle has a unique urban design and geographic challenges, bike share can open up neighborhoods and express transit to many more people if we invest to give it a real chance to succeed.

Or at least it should be. With so much of our coverage of Pronto focusing on problems with management and reasons ridership fell short of projections, let's look forward to what Pronto could be. Because while Seattle has a unique urban design and geographic challenges, bike share can open up neighborhoods and express transit to many more people if we invest to give it a real chance to succeed.

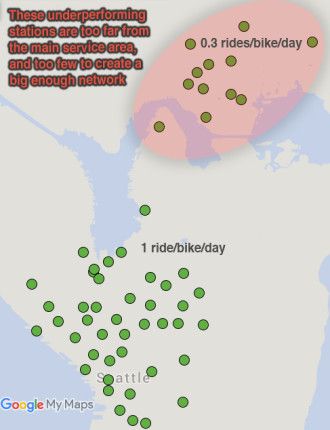

While there are many changes Seattle can make to help bike share succeed (like building the planned and funded Center City Bike Network or removing our rare adult helmet requirement), the shortest answer for why Pronto is operating over-budget is that it is just too small. With only 54 stations and 500 bikes split into two essentially distinct and even smaller systems, Pronto did not go big enough to pull a profit in its first year. This doesn't mean we should throw in the towel, it means we should invest the money now that we should have invested at launch.

Both Portland and Vancouver, B.C. have learned from Seattle's experience by planning bike share systems this year at a more appropriate scale for cities our size: BikeTown in Portland will launch with 1,000 smart bikes and 100 stations (though their bikes can be docked at any bike rack in the service area). Vancouver's system will launch even bigger with 1,500 bikes at 150 stations.

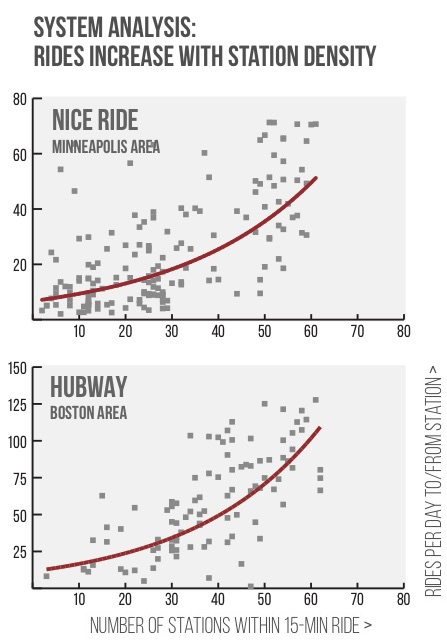

Pronto, for comparison, has only 500 bikes and 54 stations, but only 42 of those stations form a centralized and connected network. As we have discussed before, that connected network mass is everything:

From a NACTO April 2015 bike share study (PDF)

The good news is that the city's plan for expansion in 2017 is a good size: Up to 1,500 at up to 150 stations, depending on the bids potential operators propose. So what should such an expansion look like? We'll dive into that below.

First off, let's look at the just-announced planned bike share service area in Vancouver, B.C. once their system gets up to 1,500 bikes:

Our rough estimate puts this service area at about ten square miles (depending on how you factor in the water, also an issue in Seattle).

Our rough estimate puts this service area at about ten square miles (depending on how you factor in the water, also an issue in Seattle).

For comparison, here's what that service area would look like overlaid on Seattle:

Vancouver's population is much more dense than Seattle's, and its bike share system will be, as well. Their plan allows them to blanket the service area with stations every two or three blocks. In fact, their station density (15 stations per square mile) will be much higher than successful systems in DC (8.9), Boston (8.3) and Chicago (9.4). Vancouver also has high-quality bike lanes in its downtown and fewer very steep hills than Seattle. So long as the hardware rolls out without major issues (and they handle their helmet law well), Vancouver's system appears ready to thrive upon launch.

Vancouver's population is much more dense than Seattle's, and its bike share system will be, as well. Their plan allows them to blanket the service area with stations every two or three blocks. In fact, their station density (15 stations per square mile) will be much higher than successful systems in DC (8.9), Boston (8.3) and Chicago (9.4). Vancouver also has high-quality bike lanes in its downtown and fewer very steep hills than Seattle. So long as the hardware rolls out without major issues (and they handle their helmet law well), Vancouver's system appears ready to thrive upon launch.

Portland does not yet have a service area map, but it will likely be bigger than Vancouver's.

To kick off our thought experiment to plan an expanded system in Seattle, let's start with the whole city. At 84 square miles of land area, it would take a system of at least 500 stations and 50,000 bikes to cover the entire city (the city is aiming for a bare minimum of six stations per square mile). Obviously, we don't have the funds for that right now (though how cool would that be?).

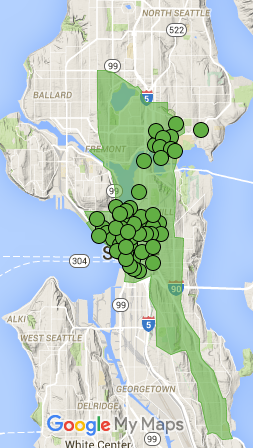

The map SDOT has been tossing around (with DRAFT in big letters) shows the following service area for a system with up to 1,500 bikes and 150 stations:

By our measure, this is around 20 square miles (again, I'm not sure how best to factor Lake Union and the Ship Canal into the square mileage). With 150 stations, the city's proposal would clock in somewhere around 7.5 stations per square mile, which is on the low end compared to other successful cities.

By our measure, this is around 20 square miles (again, I'm not sure how best to factor Lake Union and the Ship Canal into the square mileage). With 150 stations, the city's proposal would clock in somewhere around 7.5 stations per square mile, which is on the low end compared to other successful cities.

The first bit of public feedback we heard was: Where's Ballard? Well, Ballard is big and far from the rest of the service area. If we're going to add Ballard, we gotta do it right or we'll just repeat the mistakes we learned when launching the U District stations.

Note also that the Rainier Valley arm breaks several bike share rules. Most importantly, it is long and skinny, reducing the network reach of each station (top-performing stations are typically in the middle of a dense web of stations in all directions. See the graphs posted above). And perhaps just as importantly, there is no direct and easy bike route between Rainier Valley neighborhoods and the central core of the bike share system (Rainier Ave bike lanes would change this, but they're not currently in the plans for the near future).

As such, we should plan on ridership being lower than average in this area and budget accordingly. This likely means purposeful public subsidies for ongoing operations of these stations. There are great opportunities in Rainier Valley for connecting more homes and businesses to high schools and high-capacity transit. And having access to bike share offers other public benefits, such as access to a healthy way to get around and making sure city investments are not disproportionately serving wealthier and whiter parts of Seattle.

Public bikes should be for everyone. Like public transit, you don't just serve the routes that make money, you aim to serve everyone. While a for-profit business might shun providing service in Rainier Valley, as a city we can make the choice to serve the area even if it means taking a financial loss on station operations.

So with a basic understanding of the factors that make bike share work best (density of destinations, topography and popular bike routes) and maintaining the desire for a Rainier Valley launch, we thought we'd take our own stab at what an expanded bike share system in Seattle could look like. First, here's our overly ambitious map (the circles are existing stations):

This map serves population centers and popular longer-distance recreation routes (like Lake Washington Blvd and Golden Gardens). It also includes the city's Northgate expansion and the popular desire to reach Ballard. I used major bike route barriers like water, steep ridges and bridges to influence the service area. And I got rid of Queen Anne Hill from the city's map because it's just so steep (especially on bike share bikes) that it is essentially isolated from the rest of the station network.

This map serves population centers and popular longer-distance recreation routes (like Lake Washington Blvd and Golden Gardens). It also includes the city's Northgate expansion and the popular desire to reach Ballard. I used major bike route barriers like water, steep ridges and bridges to influence the service area. And I got rid of Queen Anne Hill from the city's map because it's just so steep (especially on bike share bikes) that it is essentially isolated from the rest of the station network.

Unfortunately, this map clocks in around 30 square miles, or only five stations per square mile. Without more money for more stations (we would need at least 50 more than planned), we're going to need to trim it down.

Our second try turned out like this:

The first thing we cut are those long and mostly-disconnected waterside routes like Lake Washington Blvd and the route to Golden Gardens. Instead, we focus on areas with homes and commercial centers within easy bike rides of each other. The biggest challenge to adding Ballard is the mega-steep Phinney Ridge. You pretty much need to extend the Ballard service area north to 85th in order to connect it with the rest of the system (bonus points for serving the Greenwood business district).

The first thing we cut are those long and mostly-disconnected waterside routes like Lake Washington Blvd and the route to Golden Gardens. Instead, we focus on areas with homes and commercial centers within easy bike rides of each other. The biggest challenge to adding Ballard is the mega-steep Phinney Ridge. You pretty much need to extend the Ballard service area north to 85th in order to connect it with the rest of the system (bonus points for serving the Greenwood business district).

To make up for some of this additional square mileage, we leave Northgate for a future expansion. Certainly by the time Northgate station opens there should be bike share service. But that is years away.

This map clocks in around 21 square miles, just a touch bigger than SDOT's proposal. At 7.1 stations per square mile, the station density would still be above the city's minimum of 6, but it would be lower than key peer cities that have proven successful.

Or if we want to focus on station density and connectivity, we could leave both Ballard and Northgate (as well as Sodo) for future expansions like so:

This map clocks in around 17 square miles for a healthy station density of 8.7 stations per square mile. The north section uses the steep Phinney Ridge as its natural western border.

This map clocks in around 17 square miles for a healthy station density of 8.7 stations per square mile. The north section uses the steep Phinney Ridge as its natural western border.

Seattle is not an easy city for planning a bike share system. It's got a lot of geographic challenges and oddly-shaped neighborhoods that resist a simple network of public bike stations.

But those same challenges also create the unique public spaces and magnificent views that make Seattle such a rewarding place to bike. And though biking between neighborhoods can sometimes be tough, that's where the potential for pairing transit and public bikes really starts to make sense.

For example, the Rainier Valley system will probably operate as a way to connect transit and destinations on the two main busy streets: MLK and Rainier. In much of the Valley, it's a ten-minute walk between the two streets, but a three-minute bike ride. It's a 20-minute walk from the nearest light rail station to the Hillman City business core, but a six-minute bike ride.

Likewise, bike share on Beacon Hill will connect Beacon Hill Station to many other Beacon Hill businesses and homes. And Beacon Hill bike share stations will have reasonable connectivity to the central system stations.

North of the Ship Canal, the bike share stations would have great access to both Aurora and I-5 express buses, bringing so many businesses, homes and other destinations into reach of those fast bus routes. And, of course, the system will connect with UW Link Station and the under-construction U District and Roosevelt Stations. And by connecting the Fremont, University and Montlake Bridges, there will be many more connectivity options for users that greatly expand the reach of taking bike share.

150 stations and 1,500 bikes is not big enough to get everywhere we want to go. But it is big enough to make a much more usable and powerful network. And that's what Seattle needs to realize the bike share vision we are so close to reaching.

I know people are frustrated by Pronto's budget troubles and the city's handling of the system buyout process. But don't lose sight of what we could gain if we stabilize and expand this public bike system to the size it should be.