The One Center City plan includes some bold ideas, but fails to prioritize safety

The One Center City partnership (SDOT, King County Metro, Sound Transit and the Downtown Seattle Association) announce their near-term strategies.

The One Center City partnership released a set of "near-term strategies" for a major redesign of downtown streets Thursday that would increase bus capacity, could increase car capacity, and neither commits to building a connected network of safe bike lanes nor prioritizes safety for people walking (by far the fastest-growing mode downtown).

Aside from the fact that this plan has already delayed the city's downtown bicycle network for a year, there are some good parts in it. Protected bike lanes are included in most (but not all) options. And there is a joint campaign underway to make up for lost time by expediting a connected network of bike lanes, which Seattle Neighborhood Greenway and Cascade Bicycle Club call a "Basic Bike Network."

But safety is not measured or prioritized in the One Center City plan, which is a major red flag and cause for concern and scrutiny.

You can learn more in this overview (PDF) and weigh in on the plan via this online open house.

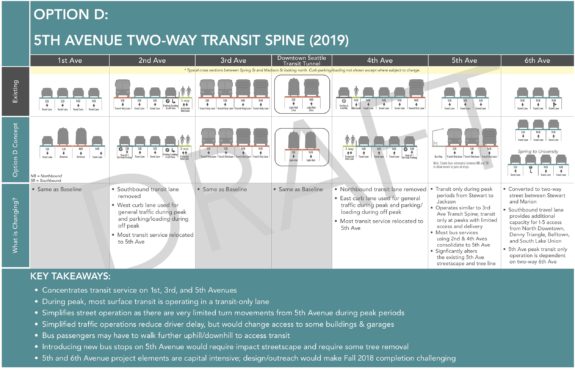

The biggest elements of the plan are focused on how to maintain bus service when all the buses currently operating in the downtown transit tunnel are kicked out, which could happen as early as autumn 2018. One bold idea includes turning 5th Ave into a two-way bus corridor, which could be great for the city and the region. We fully support bold action to maintain bus service and reliability, but won't be diving too deep into those elements in this post. For more, see posts at Seattle Transit Blog, the Urbanist and the Seattle Times.

The plan update also includes some ideas for the Pike/Pine corridor, which we will explore in a separate post. So stay tuned.

The good

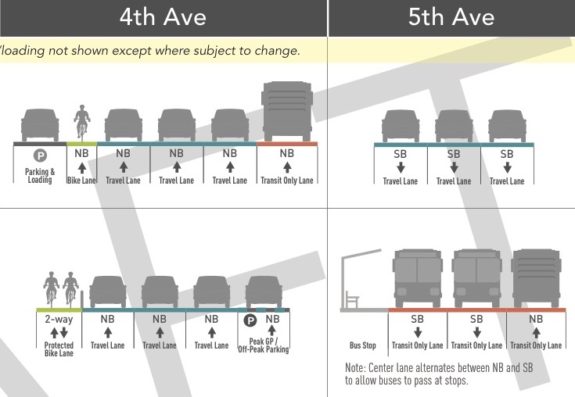

Option D includes a two-way protected bike lane on 4th Ave and a transit-only 5th Ave. Top is current, bottom is proposed. This part is awesome.

There are some very bold ideas in this plan, including a very strong idea to build a two-way bike lane on 4th Ave and turn 5th Ave into a two-way bus-only street. 6th Ave would also become a two-way street and would handle many of the car trips currently on 5th Ave. 2nd Ave would also become a busier southbound street for people driving.

Here's a bigger look at Option D, which presents the most clear and ambitious vision for a modern downtown:

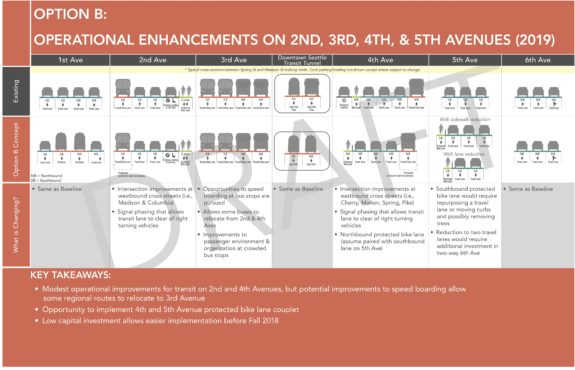

Option B is not quite as bold, but it would be cheaper and more easily delivered on time. And it includes one-way protected bike lanes as a couplet northbound on 4th Ave and southbound on 5th Ave. Many more buses would run on 2nd Ave and 4th Ave, which would get some bus lane improvements. But this plan would result in slower buses compared to Option D.

Option B is not quite as bold, but it would be cheaper and more easily delivered on time. And it includes one-way protected bike lanes as a couplet northbound on 4th Ave and southbound on 5th Ave. Many more buses would run on 2nd Ave and 4th Ave, which would get some bus lane improvements. But this plan would result in slower buses compared to Option D.

Option A is the "no change" option, which would basically just put buses on their existing no-tunnel re-routes. This option is very bad for bus service and doesn't include new bike lanes. The status quo isn't safe and would result in major bus delays.

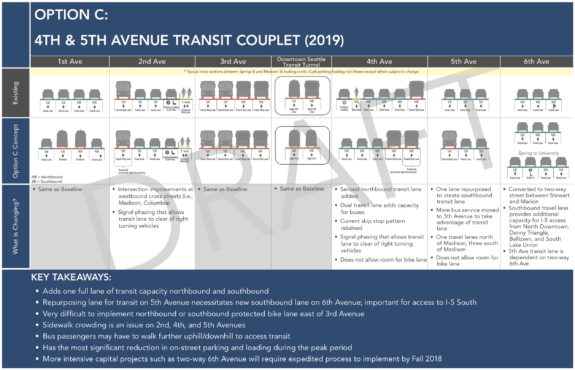

Option C is a horrible pile of planning garbage. I can't lie, I flipped out a bit when I first saw it. It's insulting and troubling that this option is even included, since it actually removes the existing bike lane on 4th Ave without adding any bike lanes to replace it.

It's 2017, Mayor Ed Murray's Vision Zero campaign to end traffic deaths and injuries has been in place for nearly two years, and here is an option to remove even the tiniest little scrap of bike lane Seattle has managed to build downtown in the past two decades.

It's 2017, Mayor Ed Murray's Vision Zero campaign to end traffic deaths and injuries has been in place for nearly two years, and here is an option to remove even the tiniest little scrap of bike lane Seattle has managed to build downtown in the past two decades.

OK, now I'm angry again. Deep breaths, Tom, deep breaths"

This option should have been disqualified before it ever saw the light of day. It disregards policies and goals developed over many years and approved by City Council. Its presence raises serious concerns about the process for creating this plan and whether the advisory group's input - they have stressed safety in their work - is being taken seriously.

Safety is not the plan's top priority, and that needs to change immediately.

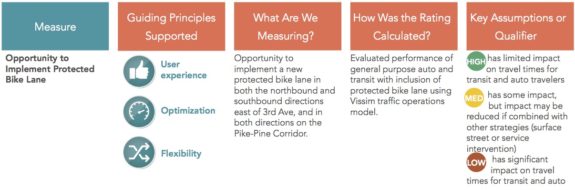

To illustrate the problem, let's take a look at how the plan is measuring priorities and outcomes. Here's how it measures bike lane "opportunity":

Bike lanes are not a central part of the plan, they are an "opportunity" to be implemented only after "evaluat[ing] performance of general purpose auto and transit." They aren't trying to measure how bike lanes would increase the number of people biking or reduce injuries and deaths. They are only measuring how bike lanes would affect cars, which is exactly backwards.

Bike lanes are not a central part of the plan, they are an "opportunity" to be implemented only after "evaluat[ing] performance of general purpose auto and transit." They aren't trying to measure how bike lanes would increase the number of people biking or reduce injuries and deaths. They are only measuring how bike lanes would affect cars, which is exactly backwards.

"Pedestrian Experience" is measured based solely on how much space there would be on sidewalks once more people are waiting for bus stops. While this is one important element to watch, there is no measurement for the safety of crosswalks where people are injured and killed far too often. Well-designed bike lanes reduce the crossing distance at crosswalks, making them safer and more comfortable. The city's excellent Vision Zero team has data to help predict increases or decreases in serious collisions with different kinds of crosswalks and bike lanes. This should be an important part of the decision.

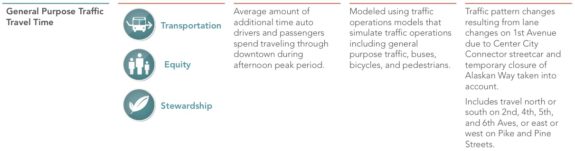

On the other hand, here's how the plan measures car travel times:

Notice the difference? In order to achieve the lowest car travel times, they are only measuring car travel times. They are not measuring how decreases in travel times impact safety for other road users. In fact, public safety outcomes are not measured in any of the plan's metrics.

Notice the difference? In order to achieve the lowest car travel times, they are only measuring car travel times. They are not measuring how decreases in travel times impact safety for other road users. In fact, public safety outcomes are not measured in any of the plan's metrics.

The safety of the people of Seattle comes first. That's the baseline. The plan shouldn't be looking at whether a bike lane allows a certain number of car trips. Instead, the plan needs to be looking at how many car trips will fit on a safe street that includes planned bike lanes and quality crosswalks.

The safety part is not negotiable.

The other problem is that the plan is measuring the movement of cars, not the movement of people and goods as is called for in the Seattle 2035 Comprehensive Plan, which was prepared by the Mayor and approved by City Council last year. An excerpt from the policy section about measuring cars vs measuring people and goods (page 91, "LOS" stands for "Level of Service," a way of measuring vehicle flow):

To accommodate the growth anticipated in this Plan and the increased demands on the transportation system that come with that growth, the Plan emphasizes strategies to in- crease travel options. Those travel options are particularly important for connecting urban centers and urban villages during the most congested times of day. Strategies for increasing travel options include concentrating development in urban villages well served by transit, completing the City's modal plan networks, and reducing drive-alone vehicle use during the most congested times of day. As discussed earlier in this Transportation element, using the current street right-of-way as efficiently as possible means encouraging forms of travel other than driving alone.

In order to help advance this Plan's vision, the City will measure the level of service (LOS) on its transportation facilities based on the share of all trips that are made by people driving alone. That measure focuses on travel that is occurring via the least space-efficient mode. By shifting travel from drive-alone trips to more efficient modes, Seattle will allow more people and goods to travel in the same amount of right-of-way. Because buses are the primary form of transit ridership in the city and buses operate on the arterial system, the percentage of trips made that are not drive-alone also helps measure how well transit can move around the city.

The One Center City Plan does not seem to be following this policy. That should change.

Improving safety downtown is more important than car travel times. Safer streets encourage more people to walk, bike or take transit, which would reduce the number of cars in downtown traffic and increase our transportation system's total efficiency. These aren't wild statements, they are adopted city policies and goals.

If safety and a reduction in drive-alone trips were priorities, I wonder what other options might have been considered in the place of Option C.

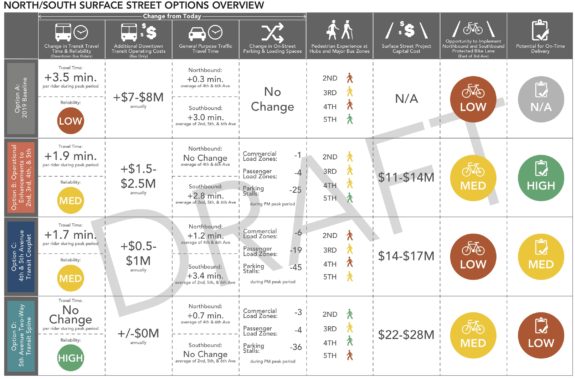

Below is how the options balance under the current (flawed) metrics:

What's next?The plan is now open to public comment, and the One Center City advisory group will have chances to guide it, as well. The draft plan for near-term strategies is due out in March (though everything about this plan seems to get delayed). Then it will be another year or so before a final plan is produced and approved by all the relevant bodies (Seattle City Council, King County Council, Sound Transit Board).

However, the city does not need to wait for the final plan before working on downtown bike lanes. SDOT Director Scott Kubly said the draft plan for these near-term strategies, due in March, will release the hold on the downtown bicycle network and guide it forward.

"It took a little bit longer than we were hoping for," Kubly said. SDOT originally told the City Council Transportation Committee that they would be at this point by July 2016. "Where we can have clear cut safety improvements, we're doing them," he said, pointing to the soon-to-be-constructed 2nd Ave bike lane extension and the mayor's recent commitment to 4th Ave.

Despite the delays, he defended the One Center City process as good for the downtown bike network.

"This will allow us to make a better investment than we could have if we started a year ago."

Let's start now on a 'Basic Bike Network' downtown

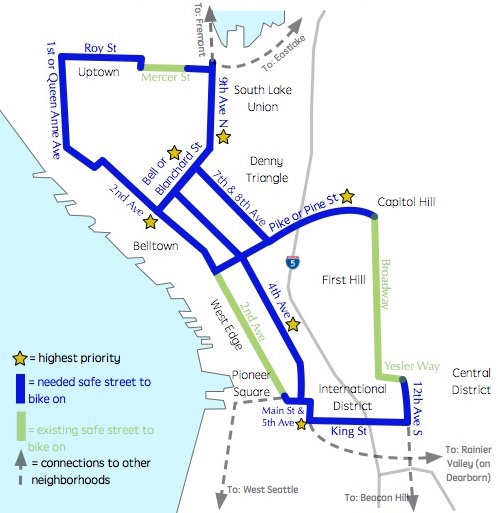

Basic Bike Network map from Seattle Neighborhood Greenways and Cascade Bicycle Club.

Now that affected corridors have been properly identified and Mayor Ed Murray has committed to bike lanes on 4th Ave, the city should work hard to make up for the last year of lost time building the downtown bike network. And that's exactly what Cascade Bicycle Club and Seattle Neighborhood Greenways have proposed in a joint plan they are calling the "Basic Bike Network."

Rather than slowly building fully-constructed bike lanes little-piece-by-little-piece, the city should move ahead quickly with a connected network of bike lanes using low-cost materials and methods in order to prioritize connectivity. Each new connection makes all the other bike lanes that much more useful, so let's connect them all at once and see how it works.

The Basic Bike Network idea can also inform the One Center City plan. The city's on-the-ground experiences with the lanes now could help guide the permanent street designs that come from the plan.

Cascade's Kelsey Mesher presented the basic bike network plan to the One Center City advisory group Thursday evening. This could be an early win for the group and for the One Center City effort as a whole.

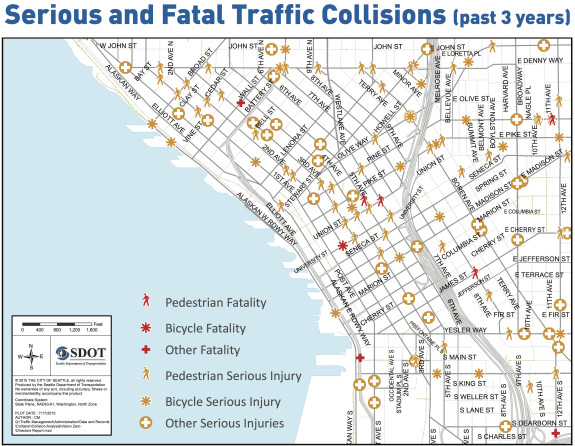

And most importantly, the city can immediately start reducing the number of people injured and killed every year on downtown streets:

Image from a 2015 open house for the now-stalled Downtown Bicycle Network.