The Happy City and our $20 Trillion Opportunity

One of the joys and frustrations of being an engineer who is also a hopeless dreamer, is that you can see the beauty of what the world could be, while also feeling the burden of every single thing that is in the way of achieving that beauty.

One of the joys and frustrations of being an engineer who is also a hopeless dreamer, is that you can see the beauty of what the world could be, while also feeling the burden of every single thing that is in the way of achieving that beauty.

Envisioning this potential (and sometimes even having the opportunity to design some of it) is one of the greatest joys of being alive. But slamming up against the stubborn wall of society's inertia, all day, every day, can lead to some displays of choice language.

If only we could grasp onto even a tiny fraction of the improvements that are hanging right in front of our faces, our society could bypass decades or centuries of pain, and billions of people could lead happier lives, starting this afternoon.

We can illustrate this problem perfectly with an example from right here in my home town. Take a look at this Google Maps satellite image of where Colorado Highway 287, (also known as Main Street) crosses over the St. Vrain Creek:

Colorado Highway 287 makes a lame leap across the creek.

It's pretty boring, right? And that is exactly my point. It's a boring, utilitarian bridge, in a blighted, shitty area of town dominated by parking lots, used car dealerships, traffic, and noise. When you drive along that part of 287, you don't even notice you are crossing a bridge. It's just part of the wide, flat road. And besides, you're busy navigating the ugly, stressful terrain of dense traffic - passing through in a rush to get to somewhere nicer.

Now, I happen to bike right under this bridge quite often, because Longmont's excellent St. Vrain Greenway path allows you whiz along through the whole town, bypassing all the trouble that the car drivers have to deal with above. Down on the bike path it's just you, recharging your soul and your muscles, passing a few other cyclists and watching the crystal clear water as it flows over oval multicolored granite rocks, maybe a few ducks and geese building nests along the water's edge.

In 2013, that Main Street bridge was partially destroyed, along with quite a few other things in town, by an enormous flood. So they decided to rebuild it. And I decided to follow along with the project, because hey, I'm an engineer.

What I learned is that building even the smallest, least noteworthy road bridge is a spectacular project. The engineering calculations alone cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. The machinery involved would fill a football field, and the quantity of soil, steel, and concrete you need to move around is difficult to even comprehend. They have been working on this one insignificant bridge for over three years now, and I'm still waiting for the bike path to re-open.

Here's a peek under the bridge. Although you rarely look at this stuff, you definitely pay for it. Just that one post-and-beam support consumes between 500,000 and 1 million pounds of concrete - releasing equivalent pollution to about 150,000 miles of driving. I would need a bigger tape measure to estimate the whole bridge, but it would be many, many times more than this. Even a small bridge is a huge thing.

The total cost was estimated at 5.6 million dollars, which puts it roughly on par with, say, this 10-bathroom waterfront megamansion compound currently for sale in Florida:

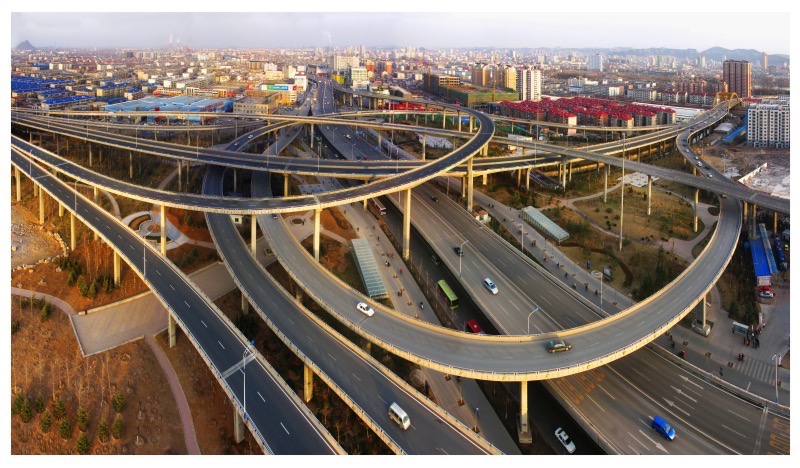

And if you want a bigger bridge, like the flyovers with cloverleafs that get built every time two highways happen to interconnect, you can spend 100 times more.

How many megamansions will this cost us?

Do you see the problem here?

This is exactly the same stuff I talk about in personal finance, except applied on a bigger scale.

The average American gets the most expensive car he can afford, and drives it as much as he can - for virtually 100% of trips out of the house. And yet he has a net worth of nearly zero, and subpar physical health, for most of his life.

The average American city builds the largest roads and parking lots it can possibly fund, maximizing the amount of available space for vehicles, in a noble attempt to reduce traffic and serve its citizens. But the result is that cities become nothing but wide, well-engineered, fast, deadly expanses of concrete. These are terrifying places for walkers and cyclists, which builds still more demand for more cars and more roads.

Let's be clear here: I'm a capitalist, lifelong student of economics, pro-growth techno-utopian, and basically the opposite of a luddite. Efficient transportation is a huge wealth-builder for society, so we will always need bridges and fast roads. But these valuable resources will always be very expensive, so it makes sense not to waste them.

A transport truck full of factory components or food brings great wealth to Longmont when it crosses that bridge over the creek. The problem is the 400 single-occupant personal cars and trucks cramming up the rest of that road, full of people who are only driving because they don't realize there is a better way.

Since even the most mundane bridge costs as much as a Mega Mansion, we are effectively building millions of mega-mansions mostly to to facilitate our clunky personal transport machines that are about 95% inefficient. And the whole reason we "need" cars in the first place is because we spread everything out by making our roads so big! It's a circular problem.

Collectively, we spend almost half of our tax dollars on paving over our living spaces, or dealing with the consequences of the lifestyle created by that pavement.

The solution in both cases is so obvious, and yet almost nobody ever talks about it. In fact, many of us are still working to perpetuate and accelerate this stupidity.

Right now, as you read this, millions of people are passionately shopping around for new, better cars, and hundreds of American cities are planning enormous expansions of their road systems - new bridges, wider lanes, bigger parking structures. Politicians whine about our "crumbling infrastructure" and vow to rebuild it with emergency packages of deficit spending. Because we obviously need to build even more of it, even faster.

To Want Something Better, You Must Understand the Core of Our Problem

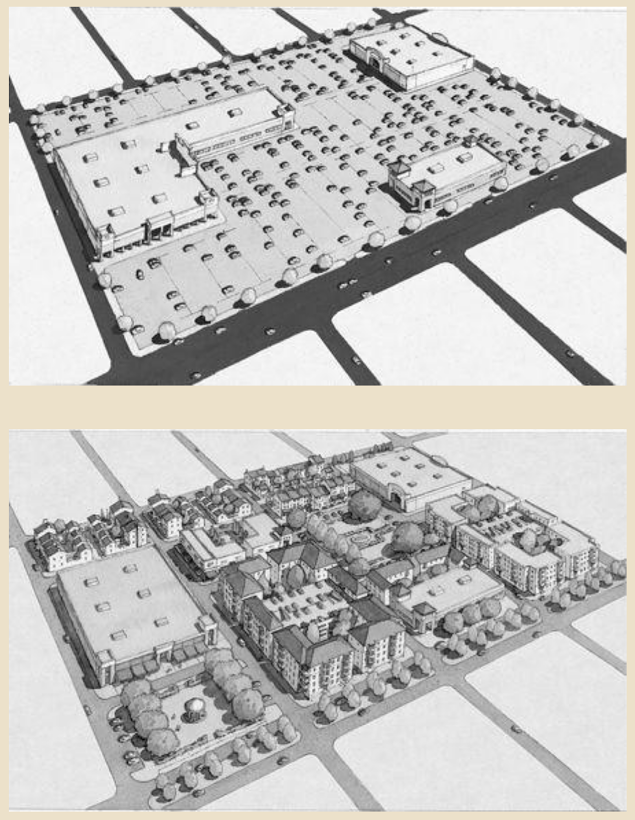

Space for cars, or for people? Two ways to use a chunk of city land. (image credit: happy city)

When you're born into a system, you come to think of it as normal. This was even true for me, growing up in an industrialized area and lusting after nice cars and motorcycles as I passed through my teens, feeling the frustration of heavy traffic jams and the joy of the open road.

But the quest for optimization led me naturally to bicycle transportation and minimizing car commutes, which led me to the study of urban planning, and the forehead-slapping realization that we're doing everything wrong.

What it didn't tell me, is how we got to this bizarre place. I mean, here are all of these relatively smart, wealthy people in this incredibly rich country, but our behavior is demonstrably self-defeating. What led us to this point, and how do we fix it?

Recently, I had the joy of reading a book about exactly this subject, from an author who has put much more thought and work into fixing it than I have. To put it moderately, it blew my mind.

Happy City, by Charles Montgomery, pretends to be a book about how cities are laid out, but you very quickly realize that it's much more - a brilliant and thoughtful book about Everything that Matters - human happiness in the past, present, and future, and just how incredibly powerful our immediate environment is, in dictating this most important thing.

As you read through the book, which I have now done twice over the past six months (something I never do), you realize that city design strongly influences everything about our lives - our health, wealth, social networks, longevity, satisfaction and our tendency towards trust or violence which in turn even dictates how we will vote*.

And yet, for over 50 years we have been designing our cities in almost the most stupid, expensive, ineffective way possible. For example, did you realize that the following stuff is studied and well-documented around the world:

- Building in the modern North American way (wide roads, big parking lots, wide lawns and plenty of space for every car) is the most expensive way that any group of humans have ever lived. We consume more concrete, water, pipes, wire, sidewalks, sign posts, landscaping, and fuel for this privilege.

- But we don't get any value for these dollars: we spend more time and money getting around than ever before, which leaves us with a chronic shortage of time to enjoy any potential benefits of dispersed living.

- People who live in suburbs are much less trusting of other people than people who live in walkable neighborhoods where housing is mixed with shops, services, and places to work. This is because they have far fewer relationships with people who live nearby. And yet the overwhelming message of happiness research is that relationships with other people have the biggest influence on our happiness.

- if 10 percent more people thought they had someone to count on in life, it would have a greater effect on national life satisfaction than giving everyone a 50 percent raise.

So we are getting a poor value for our money.

But how can it be a poor value if this is what people chose for themselves? It's the free market at work, right?

Wrong.

This is the city of Houten, just South of Utrecht and Amsterdam in the Netherlands. You can't get around the city by car, because the roads don't connect in the middle. A car would have to to drive out to the ring road, and then back in the other side. As a result, 66% of in-town trips are by bike or on foot. Also, a central train station whisks you to other cities if desired. One of my life goals is that we - quite literally you and me - build a city like this here in the USA.

The book goes on to explain the history of suburbia, which I had never quite learned before:

- Originally, we had big dense cities, small towns, and agricultural areas. The small towns were where people tended to be happiest.

- Cities expanded to meet the desires of the workers: being close to work, but also having clean air and privacy like their small town counterparts. Housing was built at the edges in "street car neighborhoods" If you have ever walked around residential San Francisco, this is the basic feel.

- When cars joined the picture, a consortium of GM, Firestone, Phillips Oil, Shell Oil, and Standard Oil bought up street car companies and shut them down. They also lobbied the government heavily and formed "Motorist Associations" to advocate for the rights of drivers - making driving more convenient and thus boosting driving demand for their products.

- Cars were originally thought of as dangerous intruders in the city. If a driver killed a pedestrian with his car, it was a crime.

The motorist associations pushed to change this balance: they sought to convince people that the problem of safety involved making sure people did not get in the way of cars.

They invented the crime of "Jaywalking", which is crossing a street somewhere other than a controlled crossing area.

They pushed in the current legal arrangement, where if you kill a person with your car, it's probably just a traffic violation. In some cases, it won't be your fault at all as long as you were obeying the rules of the road. - Motorist associations also continually push for car-friendly policies like highway expansion, fighting against traffic tickets and speed traps, and even write articles like "Elon's Carbon Con", completely misunderstanding (or deliberately misrepresenting?) the entire life purpose of one of my favorite humans.

That last bullet point strays into politics, because you get into a battle of freedom versus regulation. I personally feel that if in doubt, you should err on the side of freedom. And in this regard, the book brought up its most stunning point:

- Our current city planning method is not the result of free market forces at all. It's actually an incredibly strict book of regulations which separates functions - residential, commercial, and industrial. It also defines setbacks, lot sizes, intersections, and parking requirements. It is all standardized in a group of standard, downloadable regulations that most cities purchase from Municode, while the road design comes from the Federal Highway Association's Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUCTD).

- This is a self-replicating zombie of a system: every new town simply downloads and implements the existing book of rules without thinking about it, because "This is how things work in America"

- But that original book of rules was built from an almost comical chain of events. The oil companies and motorist associations. Special interests and racism, like a regulation in Modesto, CA which banned clothes washing facilites from the main street, which happened to be run by Chinese people. The desire of rich people to keep away poor people (which is easy to do legally if you just ban duplexes and apartment buildings, or specify a minimum lot size as many suburbs do.

- Highway subsidies, like the way we build roads with public money, lower the perceived cost of building a dispersed city. Mortgage subsidies from the federal housing association that made it easier to buy new houses than to restore or rebuild existing more central buildings.

This sounds pretty grim, but I look at it with optimism: if we have built this relatively wealthy society even with the boat anchor of horrible living design hanging around our necks, imagine how much wealthier we will become if we shed that useless burden for the next stage of our journey?

In fact, some people are already working on the project. A group called Strong Towns, run by a fiscal conservative engineer named Chuck Marohn, teaches cities about the folly of car-based expansion. From his career as a city planner, he has learned that the honeymoon of developer dollars and easy borrowing quickly fades to become a hangover of massive maintenance costs and low tax revenue. A densely packed city puts a lot of people, business, and money close together. With a dispersed city you get lots of maintenance costs but very few businesses per square mile.

A movement called "New Urbanism" started up in 1993 to bring back some aspects of people-friendly design. There are now neighborhoods popping up with these better design principles in every major city. In Mableton, Georgia they are actually reclaiming big parking lots to build useful islands of denser development, as shown in the earlier picture.

But it has been a long battle, because in order to make a place that is pleasant for people, you literally need to change or disobey the existing suburban building codes.

Here in Longmont, there is a street called "100 Year Party Court" and another called "Tenacity", named by some frustrated New Urban developers who were dumbfounded by how ridiculous the existing road regulations were: "Why are they forcing to waste space for THIS MUCH PARKING on the streetside - what are they expecting, some sort of 100-year-party?"

Thus, it is time to stop the madness and start rebuilding our ridiculous infrastructure in a smarter way.

The increase to our personal wealth may be larger than any other possible change we can make. We have about 9 million lane-miles of roads in the US, and over 5,000 notable bridges. It costs about $1 million per mile to make a single lane of road, which means we have at least $9 trillion of roads and $100 billion of bridges, before we even get into 500 million parking spaces, which cost about $4,000 each!

By Mustachian standards, at least 90% - Ninety Percent - of this pavement is wasted. It's just there to support the other sprawl, and because we have trained our citizens refuse to walk or ride a bike, even for short distances.

How To Fix It

The good news is that this can be fixed. The reason people keep perpetuating the pointless car model is that they are unaware there is any other option.

If you live in Orlando and want to go out for dinner, you see only a choice of driving, or a long, noisy walk alongside a six-lane road on a narrow grass shoulder. I was there last month and did the walk, noting that they had not even bothered with sidewalks. I could see how Orlandans would assume that cars are superior to walking, if this were their frame of reference.

Now that you know there is a better way, there are practical steps you can take as a citizen:

- Stop supporting car sprawl with your money. If a potential house, job, or store is in an area that doesn't support bikes or walking, simply don't sign the contract.

After all, would you buy a house in an area that was impossible to reach by road? Probably not, and in fact areas like this are generally called "Wilderness" because so many people insist on roads.

Reverse your priorities and insist on living somewhere designed for Humans. There are now thousands of places like this. It's worth the small effort to find one. - If you're starting or expanding your own company, do it in a walkable area. If the majority of your employees will have no choice but to drive to work, that's a bad place to start a business.

- Start voting against any road expansions in your region. Somewhat counter-intuitively, road expansions never alleviate traffic jams - they only make them worse.

The only solution to traffic is to get people out of their cars. Luckily, this solution also costs less and builds the wealth of your local economy rather than draining it. Road expansion is to a city like candy and cookies are to your body. It has also been described as "trying to cure obesity by loosening your belt" - Channel that money you would have spent on roads - 100% of it - into bike paths, road diets, parks, central city redevelopment and "upzoning".

- Fight the "Not in My Back Yard" tendencies of most people, who object to new buildings or higher-density living near where they live. What these people are probably afraid of is not the presence of more people, but the car traffic they would bring. So, support more density, but only if it discourages cars.

- Push for the removal of minimum parking requirements for new construction. Every time somebody wants to create a new building or business, our traditional building code system forces them to waste a bunch of money and precious land on parking spaces, which sit empty most of the time.

It makes much more sense to use that extra land for more businesses and housing, eliminating the vast distances that encourage people to drive in the first place. Car parking would be a niche market, built by private companies and charged out at market rates. - And of course, just start walking and biking wherever you can. In a dense city, and even in US-style suburban sprawl, a bike will get you there faster than a car most of the time. Sure, there are a few spots that are truly unsafe for bikes, but even right now, with today's infrastructure, we could eliminate at least 75% of town and city traffic overnight.

For example, here in Longmont, biking is safe and efficient to 100% of possible destinations, at least 350 days of the year. But bikes represent less than 0.5% of the traffic I see on the roads.

Every time you drive within a town, you destroy a bit of the feeling of community. Every single time you walk, you build the community, and advertise the idea of walking to every person who sees you.

As I learned from this book, urban planning is far from just a geeky niche topic - it's really the foundation of most of our wealth and personal happiness.

We can improve everything about our lives, if we all understand a bit about how to arrange our living spaces. So I'll see you out there this afternoon, as we start making some arrangements.

-

* (people who have weak bonds with their immediate neighbors will trust them less - and will also disproportionately vote for things like nationalist, anti-trade, anti-immigration policies and be worried about terrorism - sound familiar?)

Here's a cool passage on this subject from the book:

"Imagine that you dropped your wallet somewhere on your street. What are the chances you would get it back if a neighbor found it? A stranger? A police officer? Your answer to that simple question is a proxy for a whole list of metrics related to the quality of your relationship with family, friends, neighbors, and the society around you. In fact, ask enough people the wallet question, and you can predict the happiness of cities."