Natural transformations

The ladder of abstractions in category theory starts with categories, then functors, then natural transformations. Unfortunately, natural transformations don't seem very natural when you first see the definition. This is ironic since the original motivation for developing category theory was to formalize the intuitive notion of a transformation being "natural." Historically, functors were defined in order to define natural transformations, and categories were defined in order to define functors, just the opposite of the order in which they are introduced now.

A category is a collection of objects and arrows between objects. Usually these "arrows" are functions, but in general they don't have to be.

A functor maps a category to another category. Since a category consists of objects and arrows, a functor maps objects to objects and arrows to arrows.

A natural transformation maps functors to functors. Sounds reasonable, but what does that mean?

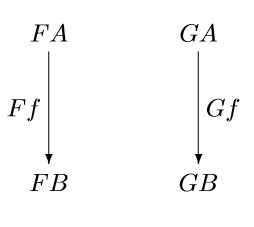

You can think of a functor as a way to create a picture of one category inside another. Suppose you have some category and pick out two objects in that category, A and B, and suppose there is an arrow f between A and B. Then a functor F would take A and B and give you objects FA and FB in another category, and an arrow Ff between FA and FB. You could do the same with another functor G. So the objects A and B and the arrow between them in the first category have counterparts under the functors F and G in the new category as in the two diagrams below.

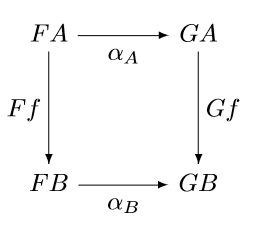

A natural transformation I between F and G is something that connects these two diagrams into one diagram that commutes.

The natural transformation I is a collection of arrows in the new category, one for every object in the original category. So we have an arrow IA for the object A and another arrow IB for the object B. These arrows are called the components of I at A and B respectively.

Note that the components of I depend on the objects A and B but not on the arrow f. If f represents any other arrow from A to B in the original category, the same arrows IA and IB fill in the diagram.

Natural transformations are meant to capture the idea that a transformation is "natural" in the sense of not depending on any arbitrary choices. If a transformation does depend on arbitrary choices, the arrows IA and IB would not be reusable but would have to change when f changes.

The next post will discuss the canonical examples of natural and unnatural transformations.

Related: Applied category theory