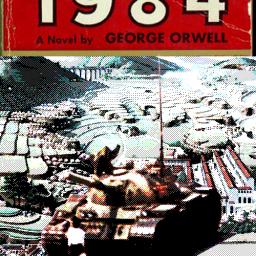

China has a very Orwellian reason for banning typing "1984" on social media, while allowing people to read Nineteen Eighty-Four

Chinese internet users can't type the numbers "1984" into social media, but Chinese bookstores freely sell copies of Orwell's novels, including Nineteen Eighty-Four, as well as other books whose titles are banned on social media.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the inner Party members are allowed to read the literature that is banned for consumption by proles and outer Party members, and the same is true in China: the Politburo treats books as the purview of intellectual elites, who are on the one hand able to circumvent these bans while traveling abroad, and, on the other hand, are more invested in the system and viewed as less likely to be subverted by Orwell's anti-authoritarian message.

This kind of double-standard is shot through Chinese censorship policy (and, as Amy Hawkins and Jeffrey Wasserstrom write in The Atlantic, through western society, too: think of how kids are banned from movies that depict nudity, but there are no age-limits on touring museums where the same nudity is on display).

The Party understands that keeping elites in line requires a lighter touch, but they treat the masses as a kind of herd that is subject to epidemics of unrest. The inconsistencies in Chinese censorship aren't the result of incoherence so much as they are a form of class warfare, where internet-bases proles are strictly limited, while the elites enjoy much more freedom of access and thought.

Western commentators often give the impression that Chinese censorship is more comprehensive than it really is due, in part, to a veritable obsession with the government's handling of the so-called "three Ts" of Taiwan, Tibet, and Tiananmen. A 2013 article in The New York Review of Books states, for example, that "to this day Tiananmen is one of the neuralgic words forbidden-not always successfully-on China's Internet." Any book, article, or social media post that so much as mentions these words, the conventional wisdom holds, is liable to disappear.

Even when it comes to the "three Ts," though, things are a bit less simple than they appear. Contra The New York Review of Books, references to Tiananmen, as a place, a tourist attraction, and so on fill the web in China. What's verboten is reference to the killings that took place around there or to the date of the 1989 massacre, June 4. Moreover, although on the mainland no bookstore would dare stock a work by a Chinese author that mentions the massacre, there is some discussion of this taboo topic in the mainland translation of a biography of Deng Xiaoping by Ezra Vogel, a prominent American scholar.

The government's approach to contentious individuals can be as surprising as its approach to contentious texts. On occasion, the government cracks down fiercely. The exiled writer Ma Jian, who has compared Xi's China to 1984, told The New York Times that, "to Chinese readers, I am a dead man," referring to the total ban on his books on the mainland. In July of last year, the political cartoonist Jiang Yefei was sentenced to six-and-a-half years in prison for "inciting subversion of state power" and "illegally crossing the border."

Why 1984 Isn't Banned in China [Amy Hawkins and Jeffrey Wasserstrom/The Atlantic]