Bill moves forward to strengthen ‘Vulnerable User Law,’ revise road sharing rules

$42.

That's the "unsafe lane change" ticket a teenager received for striking and killing John Przychodzen while he biked in the shoulder of Kirkland's Juanita Drive in 2011. Authorities claimed that because they couldn't prove he was driving recklessly, the $42 ticket was all they could give.

That $42 ticket became a rallying cry for a change in state law to increase penalties for negligent, but not criminal, driving that resulted in a serious injury or death of a "vulnerable road user," such as people walking, biking, riding an animal, using farm equipment, etc. The $42 became a symbol of the slap on the wrist too often given to people responsible for death or injury on our roads. It also became a symbol for the slap in the face victims and/or loved ones feel when they have to watch those responsible receive few or no repercussions.

But in the seven years since the law passed, law enforcement and prosecutors have not been regularly using it as was intended. So advocates such as Washington Bikes and lawmakers are working this session to pass a revised version of the law that increases penalties and makes them mandatory, putting the increased fines into a new "vulnerable roadway user education account." In the process, the bill also revises the laws around various road use responsibilities, including many biking and driving interactions.

The Senate already passed SSB 5723 (sponsored by Senators Randall, Saldana, Liias, Rolfes, Billig, and Nguyen) with a unanimous 48-0 vote (PDF). It is currently in the House Transportation Committee.

Currently, state law basically just says that someone driving a car must pass someone biking "at a safe distance." The new bill would attempt to clarify that by stating:

- "On a roadway with two lanes or more for traffic moving in the direction of travel, before passing and until safely clear of the individual, move completely into a lane to the left of the right lane when it is safe to do so

- On a roadway with only one lane for traffic moving in the direction of travel:

- (A) When there is sufficient room to the left of the individual in the lane for traffic moving in the direction of travel, before passing and until safely clear of the individual:

- (I) Reduce speed to a safe speed for passing relative to the speed of the individual; and

- (II) Pass at a safe distance, where practicable of at least three feet, to clearly avoid coming into contact with the individual or the individual's vehicle or animal; or

- (B) When there is insufficient room to the left of the individual in the lane for traffic moving in the direction of travel to comply with (a)(ii)(A) of this subsection, before passing and until safely clear of the individual, move completely into the lane for traffic moving in the opposite direction when it is safe to do so and in compliance with RCW 46.61.120 and 46.61.125."

- (A) When there is sufficient room to the left of the individual in the lane for traffic moving in the direction of travel, before passing and until safely clear of the individual:

Existing law also requires people biking to ride "as near to the right side of the right through lane as is safe" except when making a turn or passing someone. This has always been very vague because "as is safe" opens a lot of room for disagreement. For example, someone driving might not notice the road debris, traffic condition or parked car door dangers the same way someone biking does. So whose perception of safe are we talking about here? The new bill attempts to clarify some exceptions to this rule, though I imagine there is still plenty of room for disagreement. Here are some of the new exceptions:

- When approaching an intersection where right turns are permitted and there is a dedicated right turn lane, in which case a person may operate a bicycle in this lane even if the operator does not intend to turn right

- When reasonably necessary to avoid unsafe conditions including, but not limited to, fixed or moving objects, parked or moving vehicles, bicyclists, pedestrians, animals, and surface hazards

- When the operator of a bicycle is using the travel lane of a roadway with only one lane for traffic moving in the direction of travel and it is wide enough for a bicyclist and a vehicle to travel safely side-by-side within it, the bicycle operator shall operate far enough to the right to facilitate the movement of an overtaking vehicle unless other conditions make it unsafe to do so or unless the bicyclist is preparing to make a turning movement or while making a turning movement.

The bill would also define a safe passing distance as "where practicable " at least three feet." (NOTE: I corrected an earlier version in which I said the bill did not define a safe passing distance.) Close passing has always been a difficult infraction to enforce, and it's not clear that defining the distance as three feet makes enforcement any easier than requiring the passing distance to be "safe" as Washington law currently states. And really, a "safe" passing distance changes according to the speed differential. Any closer than three feet is basically always too close. But if someone is driving, say, 35 miles per hour or faster, three feet still feels very close, especially if they are driving a large truck or bus.

There are just so many gray areas out on our state's roadways, it's hard to adequately codify every possible interaction and scenario. But the new bill at least attempts to address some common causes of serious collisions.

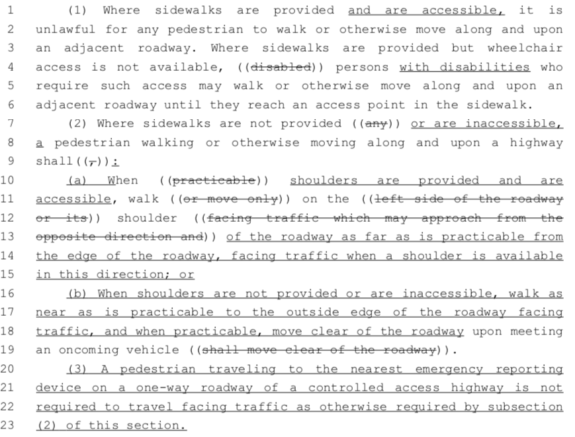

The bill also clarifies the legal rights and responsibilities of people walking and people with disabilities when sidewalks are not accessible:

In this bill text, strikethroughs show deletions and underlining shows additions. See full bill as passed by the Senate in this PDF.

Current law treats people walking on roadways without accessible sidewalks terribly, essentially telling them to jump in the bushes if a car is coming. The changes more or less recognize that a person walking along the side of a road without an accessible sidewalk has a right to exist. That's a good step in the right direction.

I would love to see a state law that requires the provision of temporary sidewalks whenever public or private works displaces one, but that is probably the job of a different bill.

A brief history of the Vulnerable User LawLeading up to the 2012 passage, safe streets advocates - including Cascade Bicycle Club and the former Bicycle Alliance of Washington - had already been working for years to pass a law that would increase non-criminal penalties for negligent driving that, while not reaching the standard of recklessness, caused immense harm or death to other road users. There were just too many cases where someone driving made a mistake while driving that killed or maimed another person and got off with no or little legal consequence. It is very painful for the victim and/or their loved ones when the person responsible is let go with essentially no consequences.

Something finally broke when that $42 ticket hit the news. Something about that number sparked outrage and became a rallying cry. It was so dramatically disproportionate to the loss of a community member's life that people demanded a change to the law so future negligent (but not criminal) driving tragedies receive more appropriate consequences.

State lawmakers passed the "Vulnerable Road User" law the next session, codifying "negligent driving in the second degree." The new offense would not be a criminal charge, and would not carry a prison sentence. This is one of the smart things about this law. If there were intent, intoxication, distraction or other forms of recklessness involved, there are existing criminal statutes authorities can pursue such as vehicular assault/homicide. But it makes little sense to lock up people for being bad drivers.

It also makes no sense to let people off with little to no consequences. They may not have intended to hurt or kill someone, but they are still responsible. So second degree negligent driving was designed to carry up to $5,000 in fines and a 90-day license suspension, though offenders could also be assigned to take traffic safety courses and relevant community service as the judge sees fit. These penalties are not commensurate with taking or injuring a life, but at least the person responsible would face more significant penalties and need to address their driving in some way.

But in the years since passage, the law just hasn't been used as intended. Law enforcement may not cite infractions correctly or prosecutors may choose not to use it, perhaps because they don't understand it. That's why the changes not only make the penalties mandatory in relevant cases, it also creates an education fund designed to help authorities better understand how to use the law and to inform the public about their responsibilities on the road.