Seattle needs a Car Master Plan

Cover image for the Seattle Car Master Plan, I assume.

Seattle has a Bicycle Master Plan, a Pedestrian Master Plan, a Transit Master Plan and a Freight Master Plan. It's well past time our city give the same treatment to the many people who drive cars in our city by creating the first ever Seattle Car Master Plan.

I am only sort of joking.

Without a Car Master Plan, many of Seattle's biggest transportation investments are being spent without a clear focus on how these public projects will help us reach our major climate change, race and social justice, public health, housing growth, and high-level transportation goals. All of the other modal master plans take these issues seriously, but those master plan projects are the exception to the rule at SDOT. The default mode of operation is that every inch of road space should go to cars unless an existing master plan says otherwise. And even then, those plans are only considered suggestions that can be ignored.

But more road space is not better for people in cars, either, though it sure seems like the mayor and SDOT's leadership has forgotten that. Building a safe bike lane on a street increases safety for all road users, including people in cars. It's not a zero-sum game. We are all in this together, and we all need to get where we're going safely.

Like the other modal plans, the Car Master Plan could study best practices for designing roads to reduce injuries and deaths for people inside and outside of cars and make recommendations for how to most safely keep cars moving on our streets. After all, getting to your destination without injuring yourself or others is undeniably the most important priority of a car trip.

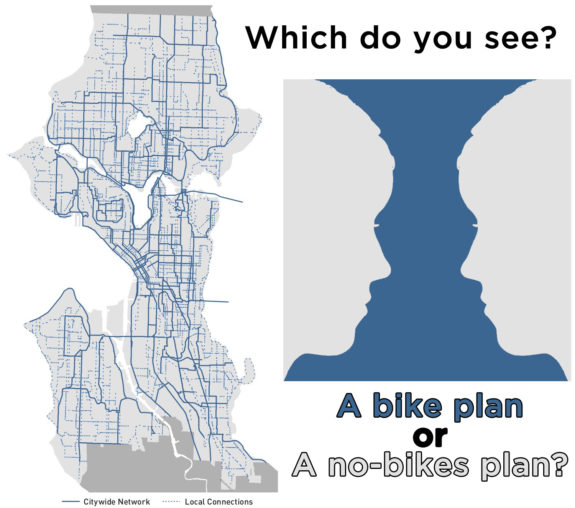

Some see a bike plan, others see a no-bikes plan

Map from the Seattle Bicycle Master Plan. Face or vase image by Nevit Dilmen, shared via Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 license as is this new image.

One big problem with having modal plans is that, depending on how the mayor or project team chooses to look at it, a master plan can either be a list of priority projects or a map of places where the safety and access needs of people biking can be ignored. After years of outreach and study, the Bicycle Master Plan includes a map of priority projects to be completed over 20 years. But project teams often cite the lack of a mention in the bike plan as justification for choosing not to make their street safer for biking.

The gray areas in the map above simply default to cars. They are reading the bike plan in the inverse, which is not how it was intended to be used. N/NE 50th Street, 25th Ave NE, and 24th Ave E are a few examples in design or construction right now that treat the plan this way. People bike on each of these streets all the time, and their safety matters even if they didn't get a blue line.

SDOT folks like to say, "not all streets can handle all modes," but it's funny how that never seems to apply to cars. Which streets can go car-free? I'd like to see that map.

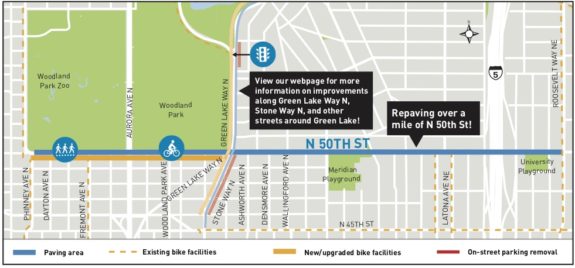

A case study: Repaving N 50th Street

NE 50th Street looking east toward I-5 from 4th Ave NE.

Project map from the N/NE 50th Street fact sheet (PDF).

Let's take the street I used as the cover image for this imaginary document: N/NE 50th Street in Fremont, Wallingford and the U District. There is nothing unusual about this project, as streets like this exist in every part of the city (though the most dangerous ones tend to be located in less wealthy and less white neighborhoods). You can replace all references to "N/NE 50th St" with the four-lane street near your house.

This street is currently slated for a massive public investment as the city prepares to repave 1.7 miles of the street from Phinney Ave N to Roosevelt Way. There is no transit service on this street, and only the westernmost blocks have bike lanes. The street is very difficult and dangerous to cross on foot because it is four lanes for most of its length. The project will improve curb ramps and repair some sidewalks, as is legally required, but it will do little or nothing to help people cross traffic safely.

Why is this project happening, and why does it disregard safety in its basic road design? You can see how misguided the project team is by this section of the project Q&A (PDF):

Q: Can you widen the street to make room for additional improvements for all modes of travel?

A: Unfortunately, we are not able to widen the street to make room for additional improvements because in most cases we'd need to acquire property " As a result, we are designing the streets to be built within the existing curbs.

Q: Will the project eliminate travel lanes?

A: The current project design will not eliminate general travel lanes"

Did you see what happened there? The project team is saying, "We are going to continue giving all the road space to cars. And if you are asking for help crossing the street or getting around safely by bike then you must be asking us to buy and demolish people's front yards, which is a very unreasonable request to make." This is the bizarre response of a team that has lost its way and needs guidance. Nobody is asking them to buy people's front yards, and they know it. People want to be able to walk and bike across and along this street in safety.

This response also points to the need for a Car Master Plan. Because any effort to get a safe crosswalk or bike lane or bus lane requires massive study and advocacy work to prove both its viability, need and public support. But extra general purpose lanes never need to go through such a process. How does the inclusion of double-barrel travel lanes help the city meets its larger goals? Will it decrease greenhouse gas emissions or help more trips shift to walking, biking and transit? Will it help the city grow equitably? Will it protect the health and safety of the people using it?

Why didn't this project ever need to answer these questions?

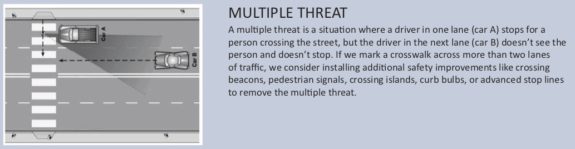

Design study: Double-barrel travel lanes

From the Seattle Safe Routes to School Engineering Toolkit (PDF).

N/NE 50th Street is four lanes for most of its length, and at most points there are multiple through lanes in the same direction. I refer to these as "double-barrel travel lanes" because they create a well-known and studied traffic danger called a "multiple threat." You may not have heard that term before, but you have experienced it. And it affects anyone trying to cross or turn left across two lanes traveling in the same direction, whether you are on foot, bike or in a car. It goes like this: You want to cross, and someone in lane closest to you stops to let you go. But you can't see around that stopped car, and neither can the person driving in the next lane over. So you step or bike or drive out just as *BOOM*, someone comes barreling through at cruising speed completely oblivious to your existence.

This scenario is the cause of very serious collisions types, including t-bone car crashes, which are among the most dangerous and deadly types of car crashes (only head-on crashes are worse). Even a street designed solely with the safety of people in cars in mind would eliminate this scenario. And the good news is that we know how to do so: Build one through lane per direction. The space freed up can be used to build bike lanes or safer crosswalks or turn lanes or space for planting trees or stormwater-cleaning bioswales or car parking or loading zones or whatever the street needs.

There is no legitimate justification for double-barrel travel lanes on a city street, yet Seattle has no process through which the building of these dangerous lanes are forced to prove their value, viability and alignment with our other city goals. And it's time for that to change.

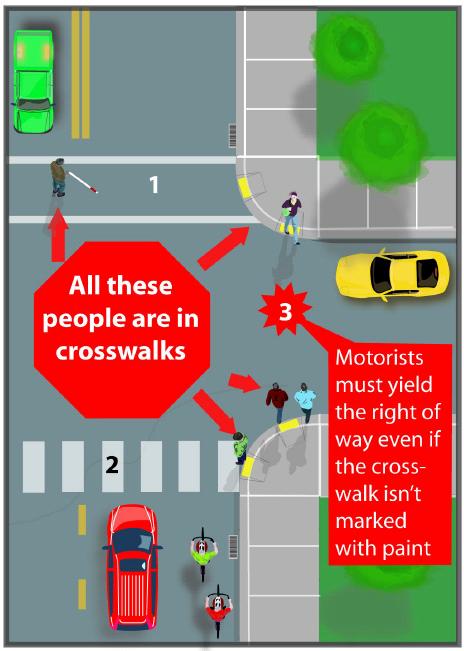

People walking should be the default mode

Image from Wisconsin Bike Fed.

Right now, SDOT's default transportation mode is driving. This is wrong, as I'm sure a Car Master Plan would note. Legally speaking, people walking have the default right of way, and our streets should reflect this. Did you know that nearly every intersection is a legal crosswalk whether it is painted as one or not? If you step off a corner into a four-lane street, for example, everyone driving is legally required to stop for you. But they won't, and that's due to the street design.

When repaving a street, SDOT should be required to design every single legal crosswalk to be safe to use. Or to put it another way, a person walking should always be able to cross the street. It is SDOT's job to make sure their street design encourages legally-required yielding, and a great side-effect would be that many more trips in the area would become more viable by foot or other assistive mobility device because people would not need to walk blocks out of the way just to get to a safe crosswalk.

All crosswalks should be legally required to achieve some high compliance threshold (preferably 100 percent, though there are always a few jerks who just don't care). But SDOT continues to design streets with legal crosswalks they know will not be respected by people driving. This is unethical, and it's clear that nothing short of a change in law will shift the department's anti-walking priorities.

The same goes for the use of beg buttons that are used as a way to skip walk signals entirely when nobody pushed the button in time. This results in dangerous situations where people realize too late that they are getting skipped and make a run for it. There are also walk signals where people are expected to wait far longer than is reasonable. There should be reasonable limits on how much time is allowed between walk phases.

And all this would fit perfectly in a Car Master Plan, because it is clearly in the best interest of people driving that they don't hit somebody trying to cross an unsafe street.

Vision Zero and complete streets with teethWow. This is powerful. Ghost traffic carnage. People are dying on our streets so in all kinds of ways. These collisions are preventable, we just need to stop being numb to it. https://t.co/OmnLCDzaiI

- Seattle Bike Blog (@seabikeblog) April 26, 2019

OK, this post have been mostly in jest because every point I have made about why we need a Car Master Plan has already been codified elsewhere, most explicitly in the city's Vision Zero plan and complete streets ordinance. But these documents are not being seriously followed, and that needs to change. Perhaps it's time for the City Council to pass a complete streets ordinance that actually has teeth. We need a law that requires the city to make streets safer for all road users, not one that merely forces the city to "consider" their needs. Because someone who is injured while crossing double-barrel travel lanes is not helped by the project team's consideration.

Perhaps we also need to specifically identify dangerous road conditions that SDOT must eliminate when conducting road work, including double-barrel travel lanes, extra-wide travel lanes, slip lanes for fast turning and beg buttons that require a push to activate the walk signal. Because the department continues to ignore these safety issues unless projects are specifically safety projects, likely from a modal master plan.

Cambridge recently passed a law that essentially requires the city to build protected bike lanes that are in their bike plan when repaving those streets. Seattle could consider that, as well. And, as we've noted before, this would also help people driving because bike lanes aren't actually for people biking, they are for people driving. Infrastructure that helps people driving avoid breaking the law or injuring other people is good for people driving.

That's why eliminating bike lanes and cutting the bike plan is bad for people driving, too. Because the bike plan isn't just for people who bike, it is a vision document for our city's future. It is for everyone, even if they don't bike themselves.