Golay codes

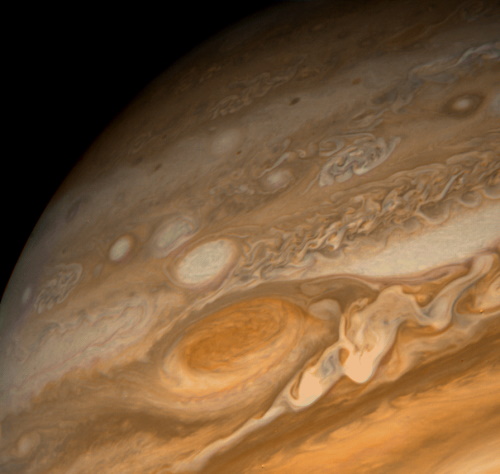

Suppose you want to sent pictures from Jupiter back to Earth. A lot could happen as a bit travels across the solar system, and so you need some way of correcting errors, or at least detecting errors.

The simplest thing to do would be to transmit photos twice. If a bit is received the same way both times, it's likely to be correct. If a bit was received differently each time, you know one of them is wrong, but you don't know which one. So sending the messages twice doesn't let you correct any errors, but it does let you detect some errors.

There's a much better solution, one that the Voyager probes actually used, and that is to use a Golay code. Take the bits of your photo in groups of 12, think of each group as a row vector, and multiply it by the following matrix, called the generator matrix:

100000000000101000111011010000000000110100011101001000000000011010001111000100000000101101000111000010000000110110100011000001000000111011010001000000100000011101101001000000010000001110110101000000001000000111011011000000000100100011101101000000000010010001110111000000000001111111111110

(You might see different forms of the generator matrix in different publications.)

That's the (extended binary) Golay code in a nutshell. It takes groups of 12 bits and returns groups of 24 bits. It doubles the size of your transmission, just like transmitting every image twice, but you get more bang for your bits. You'll be able to correct up to 3 corrupted bits per block of 12 and detect more.

Matrix multiplication here is done over the field with two elements. This means multiplication and addition of 0's and 1's works as in the integers, except 1 + 1 = 0.

Each pair of rows in the matrix above differ in 8 positions. The messages produced by multiplication are linear combinations of these rows, and they each differ in at least 8 positions.

When you receive a block of 24 bits, you know that there has been some corruption if the bits you receive are not in the row space of the matrix. If three or fewer bits have been corrupted, you can correct for the errors by replacing the received bits by the closest vector in the row space of the matrix.

If four bits have been corrupted, the received bits may be equally close to two different possible corrections. In that case you've detected the error, but you can't correct it with certainty. If five bits are corrupted, you'll be able to detect that, but if you attempt to correct the errors, you could mistakenly interpret the received bits to be a corruption of three bits in another vector.

Going deeperIn one sense, Golay codes are very simple: just multiply by a binary matrix. But there's a lot going on beneath the surface. Where did the magic matrix above come from? It's rows differ in eight positions, but how do you know that all linear combinations for the rows also differ in at least eight positions? Also, how would you implement it in practice? There are more efficient approaches than to directly carry out a matrix multiplication.

To give just a hint of the hidden structure in the generator matrix, split the matrix half, giving an identity matrix on the left and a matrix M on the right.

101000111011110100011101011010001111101101000111110110100011111011010001011101101001001110110101000111011011100011101101010001110111111111111110

The 1's along the last row and last column have to do with why this is technically an "extended" Golay code: the "perfect" Golay code has length 23, but an extra check sum bit was added. Here "perfect" means optimal in a sense that I may get into in another post. Let's strip off the last row and last column.

1010001110111010001110011010001111011010001111011010001111011010000111011010000111011010000111011011000111011001000111011

The first row corresponds to quadratic residues mod 11. That is, if you number the columns starting from 0, the zeros are in columns 1, 3, 4, 5, and 9. These are the non-zero squares mod 11. Also, the subsequent rows are rotations of the first row.

Golay codes are practical for error correction-they were used to transmit the photo at the top of the post back to Earth-but they also have deep connections to other parts of math, including sphere packing and sporadic groups.

Related posts- Check sums and error detection

- Vehicle identification numbers (VINs)

- Using error correcting codes in cryptography