Caltech and JPL Firing Quadrotors Out of Cannons

As useful as drones are up in the air, the process of getting them there tends to be annoying at best and dangerous at worst. Consider what it takes to launch something as simple as a DJI Mavic or a Parrot Anafi- you need to find a flat spot free of debris or obstructions, unfold the thing and let it boot up and calibrate and whatnot, stand somewhere safe(ish), and then get it airborne and high enough quick enough to avoid hitting any people or things that you care about.

I'm obviously being a little bit dramatic here, but ground launching drones is certainly both time consuming and risky, and there are occasions where getting a drone into the air as quickly and as safely as possible is a priority. At IROS in Macau earlier this month, researchers from Caltech and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) presented a prototype for a ballistically launched drone-a football-shaped foldable quadrotor that gets fired out of a cannon, unfolds itself, and then flies off.

Test launching the SQUID (Streamlined Quick Unfolding Investigation Drone) from a truck as shown in the video effectively demonstrates why this is more than a novelty: It would otherwise be very difficult to conventionally launch a quadrotor from a vehicle moving that fast. You can imagine how useful this would be for first responders, ships dealing with waves, or even other aircraft in flight.

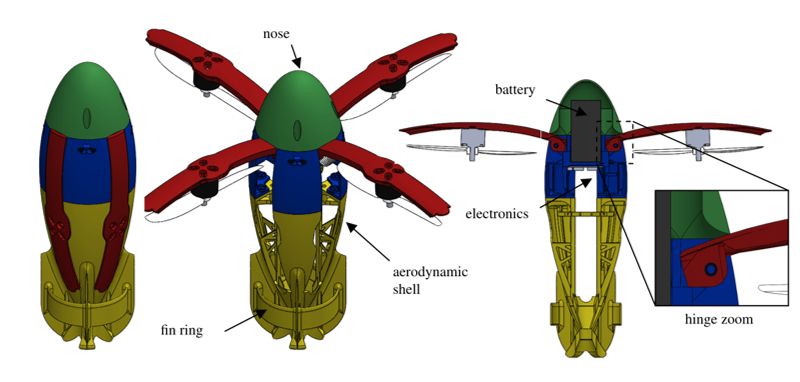

Image: Caltech & NASA JPL A CAD model of the SQUID system showing (from left): ballistic configuration, multirotor configuration, and section view with a closer look of a hinge.

Image: Caltech & NASA JPL A CAD model of the SQUID system showing (from left): ballistic configuration, multirotor configuration, and section view with a closer look of a hinge. The prototype SQUID shown here weighs 530 grams and is about 27 centimeters long. Folded up, it's just over 8 cm in diameter. SQUID gets its initial boost of 15 meters per second (referred to as "muzzle velocity" in the paper) from a pneumatic baseball pitching machine, which gives the drone an apex of about 10 m. Immediately after the drone exits the launcher, a nichrome wire heats up and burns through a monofilament line holding the arms in place. Driven by springs, the arms snap out in just 70 ms, while the aerodynamic body of the drone passively orients it into the airstream.

As soon as the motors spin up (after about 200 ms), SQUID automatically orients itself into a hovering attitude, and it can be controlled just like a normal quadrotor within less than 1 second of launch. Landing is a bit of a challenge, although apparently "it can safely land if the bottom touches the ground first at a low speed," after which it'll gently topple over.

SQUID's design is easily scalable, and the researchers are currently working on both smaller (2-inch diameter) and larger (6-inch diameter) prototypes. The 6-inch SQUID would be large enough to carry a battery and payload enabling significantly more autonomy, including vision-based ballistic stabilization.

Image: Caltech & NASA JPL To test the drone, the researchers launched it from a moving vehicle up to 50 mph.

Image: Caltech & NASA JPL To test the drone, the researchers launched it from a moving vehicle up to 50 mph. We should mention that ballistically launched drones aren't a completely new idea-we've seen a couple of examples in the past, like this very satisfying-sounding system from Raytheon. But getting something similar to work for a quadrotor is a bit more difficult, and as far as we know, nobody else has thought about applying this launch technique to drones for planetary exploration:

"Design of a Ballistically-Launched Foldable Multirotor," by Daniel Pastor, Jacob Izraelevitz, Paul Nadan, Amanda Bouman, Joel Burdick, and Brett Kennedy, from Caltech, JPL, and Olin College, was presented at IROS 2019 in Macau.While the SQUID prototype, as outlined in this paper, has been designed for operation on Earth, the same concept is potentially adaptable to other planetary bodies, in particular Mars and Titan. The Mars helicopter, planned to deploy from the Mars 2020 rover, will provide a proof-of-concept for powered rotorcraft flight on the planet, despite the thin atmosphere. A rotorcraft greatly expands the data collection range of a rover, and allows access to sites that a rover would find impassible. However, the current deployment method for the Mars Helicopter from the underbelly of the rover reduces ground clearance, resulting in stricter terrain constraints. Additionally, the rover must move a significant distance away from the helicopter drop site before the helicopter can safely take off. The addition of a ballistic, deterministic launch system for future rovers or entry vehicles would isolate small rotorcraft from the primary mission asset, as well as enable deployment at longer distances or over steep terrain features.