How Violence and Segregation Destroyed African American Innovation

In 2014, economist Lisa D. Cook reported research that illuminated something fundamental about innovation: No matter how well your IP laws are written, innovation won't happen without security and the rule of law. To prove that she showed how segregation laws, lynchings, and state-supported violence suppressed African American invention during the 20th Century. By tracking the patent filings of African American inventors from 1870-1940, Cook showed that acts of violence have a measurable impact on innovation. IEEE Spectrum spoke to the Michigan State University professor of economics and international relations on 2 July 2020.

IEEE Spectrum: What led you to investigate the effects of violence and segregation on African American innovation?

Lisa D. Cook

Lisa D. Cook Lisa D. Cook: I wrote my dissertation on Russia and the Russian economy. This was in the 1990s, and it was a bit of a dangerous place. There was a question that always came up when I was talking to entrepreneurs there: "Why can't we get invention and innovation in Russia?"

They were asking a legitimate question, because they already had IP laws on the books. They were much different from the laws in the Soviet period, which weren't very strong. They were just wondering why invention wasn't happening at the pace they thought it should be happening. So I said to them, "Well, you've got to have things like the rule of law. You've got to have personal security."

At the time, I didn't have any sort of empirical evidence that could show this. The conventional wisdom in the economics of innovation literature then was that if you have these strong IP laws, that would be sufficient to provide an incentive for patenting. I found that naive.

So I wondered if there might be a historical experiment that might show this. One that would have an IP regime that stayed the same for some inventors but have other inventors subject to some sort of shock that had to do with violence or lack of rule of law. And I thought, "Well, that describes the United States. So maybe we can find this experiment in U.S. history." You have a control and a treatment group. And the African Americans were going to be the treatment group.

IEEE Spectrum: How did you actually figure out which inventors were African American during your 1870-1940 study period, given that patent applications don't list race?

Lisa D. Cook: I thought that was going to be easy, because there's this emerging literature on Black names in economics. So I thought I could use the same techniques that my colleagues used at the time. I tried that. Then using census data, I came up with the first-ever list of historical black names. And it was of limited use. It barely identified anybody among the African American inventors.

So I had to try a new method. And that was finding all of the directories of scientists, engineers, and potential inventors that I could. In doing so, I found the survey of Henry Baker, the African American patent examiner in the early 1900s, who conducted surveys of patent agents and patent attorneys in 1900 and 1913.

That was very useful as a start. But it wasn't perfect. So I had to extend it backwards and forwards and check everything, as well. I also checked things like obituaries, because one thing that I knew from all these directories that I was collecting was that they biased the sample towards famous people. So I thought I might get some equalization by just checking newspapers and checking obituaries. And I was able to recover some that way.

IEEE Spectrum: That sounds like a ton of work.

Lisa D. Cook: It was.

IEEE Spectrum: Would you briefly explain the key results?

Lisa D. Cook: The main results over the period are, first, that violence has an impact on all patenting. It has a significant and negative impact on Black patenting. So those who were targeted are going to be disproportionately affected by lynchings, riots, and segregation laws.

Second, the most valuable patents are the most affected by violence. And that's not good news if you're extrapolating this to an economy.

The next group of results would suggest that if White inventors had been subjected to the same type of violence, economic growth would have been a lot slower. Why? Because business investment would have been lower, and business investment is a key component of GDP. So we would have had fewer inventions and fewer patented inventions and therefore less business investment and therefore less growth.

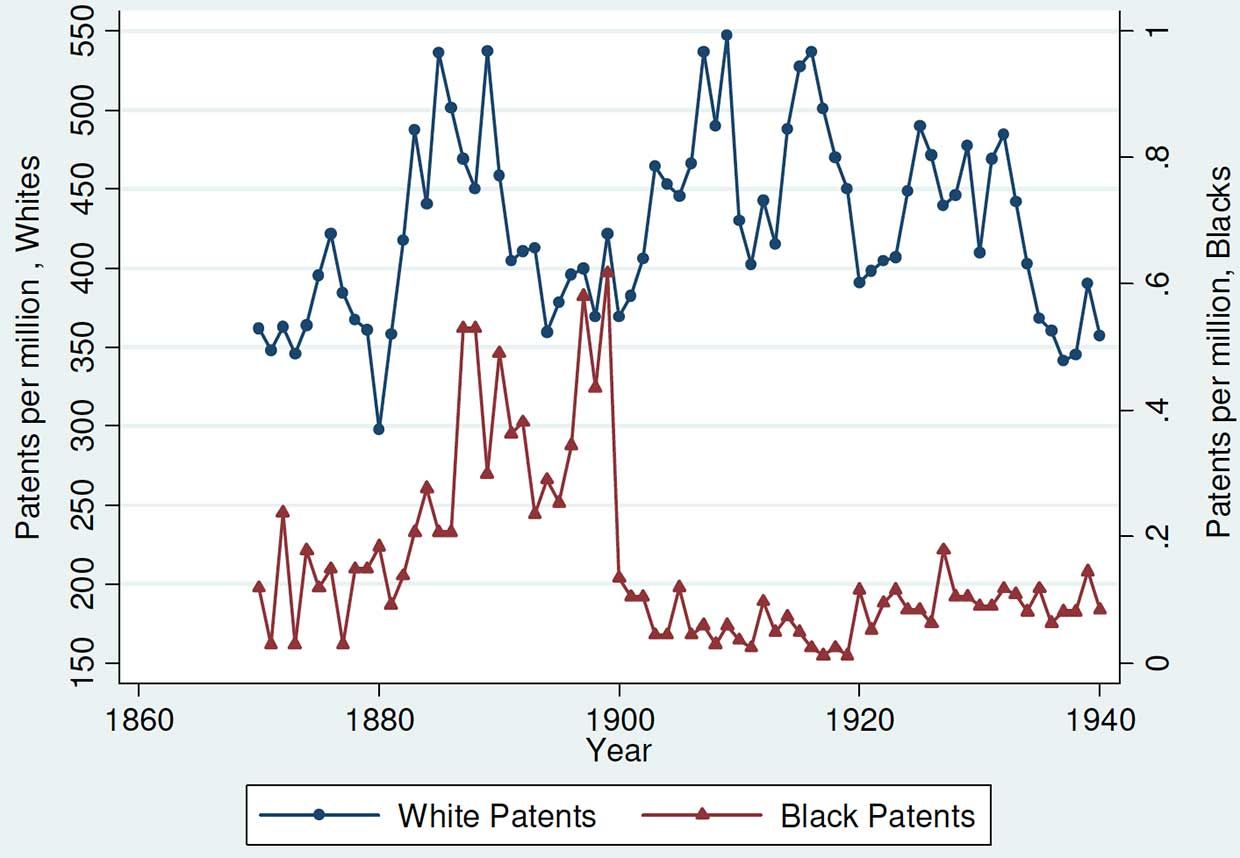

Source: Violence and Economic Growth: Evidence from African American Patents, 1870-1940," Lisa D. Cook, Journal of Economic Growth, Volume 19 Issue 2 (June 2014), pp. 221-257 African American patenting increased following the Civil War until a U.S. Supreme Court decision led to the spread of segregation laws around 1899. (Patents plotted by year granted.)

Source: Violence and Economic Growth: Evidence from African American Patents, 1870-1940," Lisa D. Cook, Journal of Economic Growth, Volume 19 Issue 2 (June 2014), pp. 221-257 African American patenting increased following the Civil War until a U.S. Supreme Court decision led to the spread of segregation laws around 1899. (Patents plotted by year granted.) IEEE Spectrum: Electrical patents were particularly affected. Why?

Lisa D. Cook: I separated patents into types of technological categories to see if one category was more affected by violence than others. And we did see that violence disproportionately affected-for that period-electrical patents, which would have been some of the most valuable.

You can imagine how that would be true: You really had to be up on the latest inventions and the latest patents to be able to be productive, to add an increment to the stock of knowledge. Electrical patents, at the time, would probably have taken more collaboration with other inventors and more trips to the patent attorney. And that was something that was cut off as a result of Plessy v. Ferguson [the disastrous 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision that legitimized anti-Black laws passed by U.S. state legislatures beginning in the late 19th century]. You can imagine that if an inventor no longer had access to, for example, the main library, where patent registries and information about new inventions were and where inventors could gather, that would be detrimental to the free flow of information. If commercial business districts were segregated-there were no patent attorneys who were African Americans until the 1970s-that meant that you really didn't have access to someone who could file and protect your invention.

IEEE Spectrum: What key events impacted African American innovation?

Lisa D. Cook: Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 was a big one. 1899 was the peak for African American invention, and even using 2010 data [PDF} it was still the peak per capita for African American invention.

Scholars of constitutional law explain that the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court rulings took two or three years to produce effects, for rulemaking to happen, and for laws to be passed. What we did see was a proliferation of laws after Plessy v. Ferguson in states, especially outside of the south, and that's where patenting was happening. So I think it was largely Plessy v. Ferguson that led to this huge drop in patenting by African Americans that hasn't yet recovered.

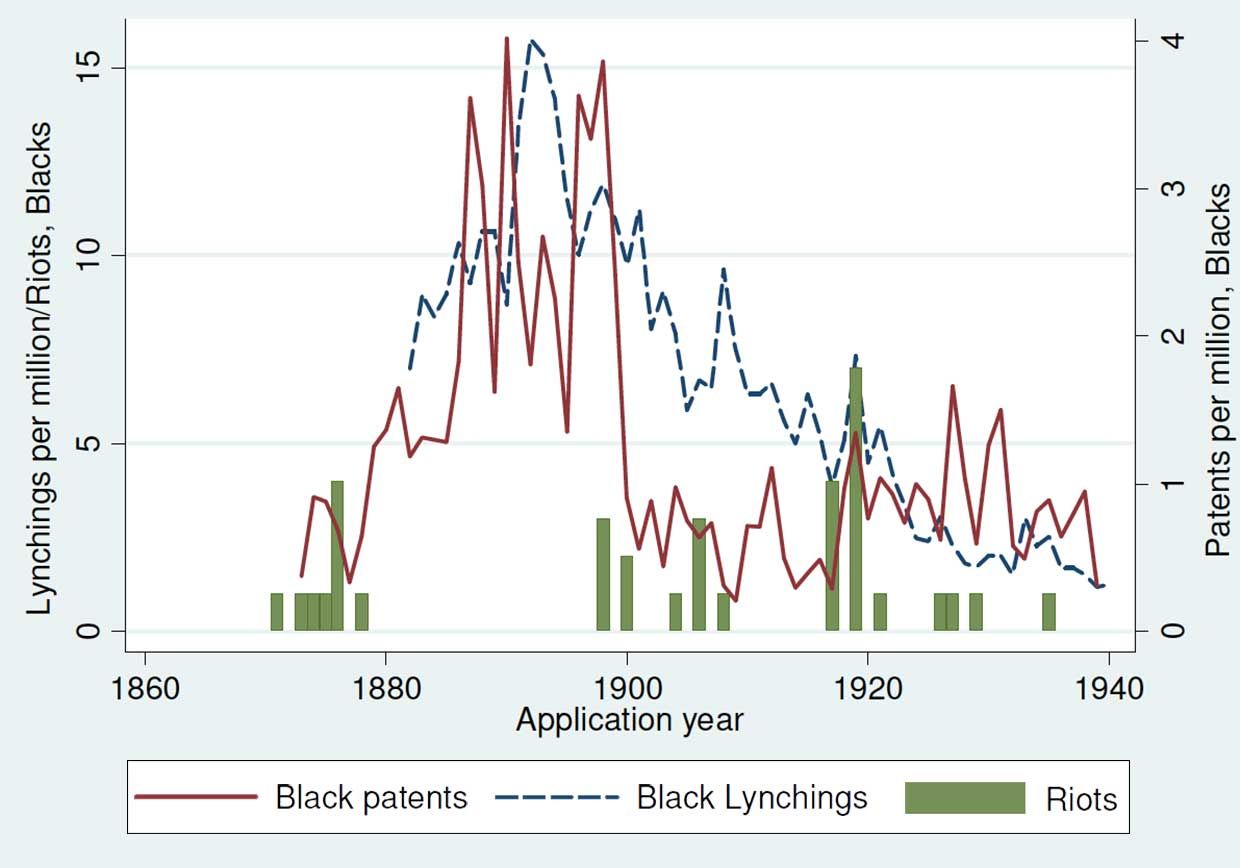

Blatant violence also had an effect. Before I did anything, I had looked at the time series of patents and I'd noticed several dips. One was 1899, and another one was in 1921. The first thing I did, being an economist of innovation, was try to see if the patent laws changed or if patents became more expensive. But the only thing I came up with was the Tulsa massacre. [In May and June 1921, a White mob attacked and destroyed a relatively wealthy African-American neighborhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Many in the mob had been deputized and armed by government officials, and the attack included aerial bombardment.] The local, state, and federal government failed African Americans so much in Tulsa that it had a sizeable effect on all African Americans. They felt terrorized at the time, and there was nobody who had their backs. So I think that that's why 1921 stood out in the data, and I think there's evidence to support that.

Source: Violence and Economic Growth: Evidence from African American Patents, 1870-1940," Lisa D. Cook, Journal of Economic Growth, Volume 19 Issue 2 (June 2014), pp. 221-257 Violence against African Americans, notably the 1921 Tulsa Massacre, suppressed patenting. (Patents plotted by application year.)

Source: Violence and Economic Growth: Evidence from African American Patents, 1870-1940," Lisa D. Cook, Journal of Economic Growth, Volume 19 Issue 2 (June 2014), pp. 221-257 Violence against African Americans, notably the 1921 Tulsa Massacre, suppressed patenting. (Patents plotted by application year.) IEEE Spectrum: How much potential innovation was lost during that period, and how did you figure that out?

Lisa D. Cook: I extrapolated the trajectory from the pre-1900 trend and found that in the absence of violence and segregation, there should've been roughly 1100 patents at the time. That would've been the output of a mid-sized European country then. But what I found was 726 patents.

IEEE Spectrum: What does your research say generally about violence and innovation?

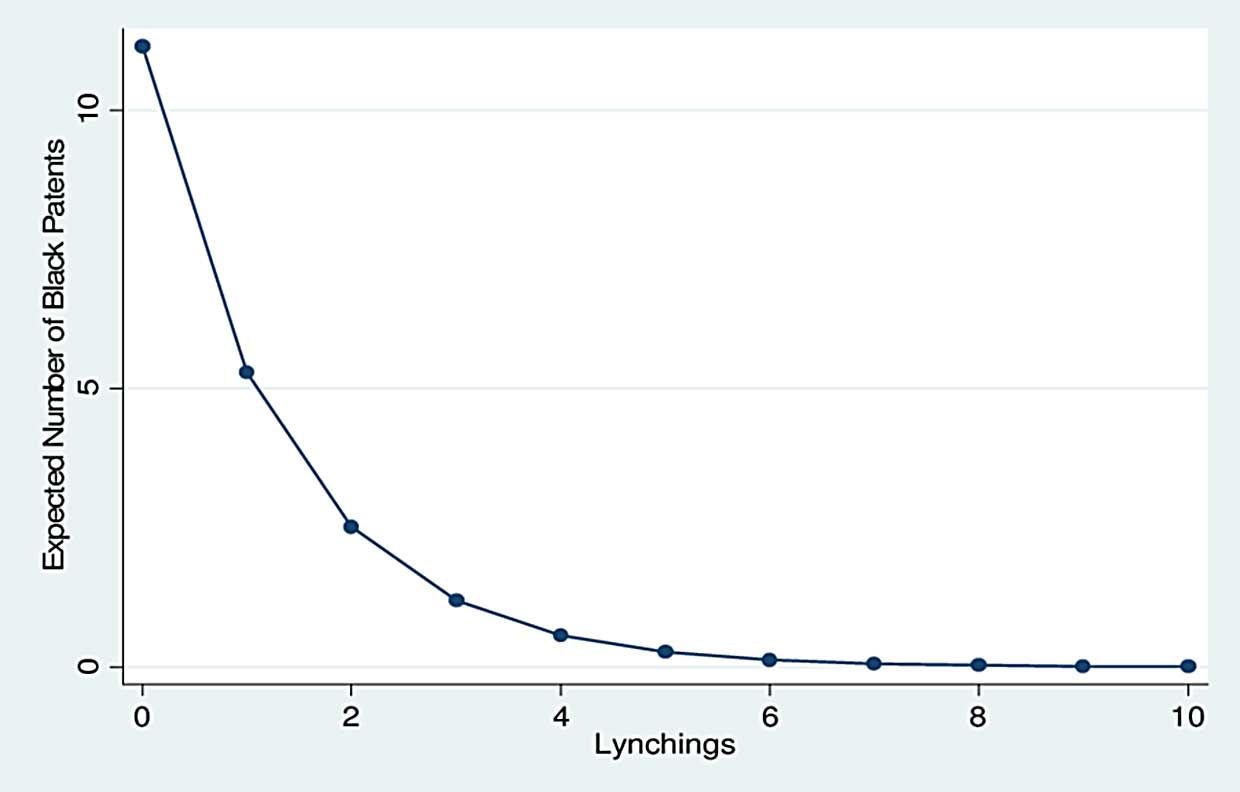

Lisa D. Cook: In the 2014 paper, what I did was to predict which lynchings (of a series of lynchings) would have the greatest impact on patenting, and it's the first one. So that's the one that you want to try to prevent. There are ways to do this, such as not letting white supremacist groups get out of control.

I think we don't think enough about the conditions that inventors need to be productive, such that there can be a free flow of ideas. I think we put too much weight on the actual laws in place and not the environment in which they are operating. We have direct evidence that the conditions in which one is operating can make a huge difference, whether you're adding to the stock of knowledge broadly or the stock of knowledge related to science and innovation.

Source: Violence and Economic Growth: Evidence from African American Patents, 1870-1940," Lisa D. Cook, Journal of Economic Growth, Volume 19 Issue 2 (June 2014), pp. 221-257 The first lynching has the most powerful effect on innovation.

Source: Violence and Economic Growth: Evidence from African American Patents, 1870-1940," Lisa D. Cook, Journal of Economic Growth, Volume 19 Issue 2 (June 2014), pp. 221-257 The first lynching has the most powerful effect on innovation. IEEE Spectrum: What is holding back black entrepreneurship now?

Lisa D. Cook: I think that one of the big things that is holding back African American participation and women's participation is workplace climate, frankly. There are three stages of innovation-education; training as an inventor, working in a lab, for example; and then the third phase, commercialization of the invention. There are well-known problems associated with workplace climate in each. There is systemic racism at every stage.

With respect to entrepreneurship at the very end, what I found in doing my research interviews is that networks matter a lot more than we have researched in economics. It is social networks, all types of networks that require engagement-like having an internship at an investment bank, or being a member of a golf club-that are needed to get inventions commercialized. Those networks result in introductions for venture capital funding, for example. And African Americans and women are often kept out of those networks. So it's unsurprising that 1 percent of founders who received VC funding are Black.

To Probe Further:

For more on Cook's work on violence and innovation, listen to her 11 February 2019 interview with National Public Radio's Cardiff Garcia How Violence Limits Economic Activity." And read her chapter The Innovation Gap in Pink and Black," in Does America Need More Innovators? MIT Press, 2019.

For more about race and the process of innovation see The implications of U.S. gender and racial disparities in income and wealth inequality at each stage of the innovation process," (with Jan Gerson), WashingtonCenter for Equitable Growth Policy Brief, July 2019.