When They Electrified Christmas

In much of the world, December is a month of twinkling lights. Whether for religious or secular celebrations, the variety and functionality of lights have exploded in recent years, abetted by cheap and colorful LEDs and compact electronics. Homeowners can illuminate the eaves with iridescent icicles, shroud their shrubs with twinkling mesh nets, or mount massive menorahs on their minivans.

But decorative lights aren't new. On 22 December 1882, Edward H. Johnson, vice president of the Edison Electric Light Co., debuted electric Christmas lights when he lit up 80 hand-wired bulbs on a tree in the parlor of his New York City home. Johnson opted for red, white, and blue bulbs, and he mounted the tree on a revolving box. As the tree turned, the lights blinked on and off, creating a "continuous twinkling of dancing colors," as William Croffut reported in the Detroit Post and Tribune. (Croffut's account and many other wonderful facts about the history of decorative lights are available on the website Old Christmas Tree Lights.)

Two years later, Johnson's growing display caught the attention of the New York Times. His tree now boasted 120 lights and more colors. He also created a fire "burning" in the fireplace; in reality, it was colored paper illuminated from below by electric lights.

Johnson was part early adopter, part showman, and part publicist for the possibilities of electricity. But electric Christmas lights were not exactly practical at the time because most homes were not yet wired for electricity. Lighting had to be hand wired, and there was no standardization in bulbs or sockets. For the next several decades, decorative lights remained the playthings of the wealthy elite.

In 1903, GE rocked the home-decorating world by introducing the first strings of prewired light sockets.

Meanwhile, manufacturers continued to market new products. In 1890, the Edison Lamp Co. began advertising miniature incandescent lamps that could be interwoven into garlands or used for decorating Christmas trees. A 1900 advertisement from General Electric (formed through the 1892 merger of Edison General Electric and Thomson-Houston Electric) touted the advantages of electric Christmas lighting over gas and candles: "No Danger, Smoke or Smell." Customers not quite willing to commit to the lights could rent them for the season.

In 1903, GE rocked the home-decorating world by introducing the first strings of prewired light sockets. The GE lights came in strands, or festoons, of 8, 16, 24, or 32 bulbs. Additional 8-bulb festoons could be added as desired. The sets included 50 feet (15 meters) of flexible cord and screwed into a lamp socket. The lights were connected in series, so if a bulb burned out, the rest of the line went dark. Detailed instructions described how to troubleshoot problems if the lights did not shine. A 24-light set cost US $12 (about $325 today) and could illuminate a medium table-top tree.

The GE lights were still out of reach for the average consumer, but prices quickly dropped as competitors entered the market. Just four years later, Excelsior Supply Co. of Chicago advertised "Winking Fairy Lights for Christmas Trees" in Hardware Dealers' Magazine. Each 8-bulb set cost only $5, with a wholesale price of $3.50.

U.S. President Grover Cleveland was an early adopter of the electrified Christmas tree, as shown in this 1896 photo. White House Historical Association

U.S. President Grover Cleveland was an early adopter of the electrified Christmas tree, as shown in this 1896 photo. White House Historical Association

The earliest Christmas lights used miniature versions of Edison's pear-shaped carbon-filament bulbs, which had fragile exhaust tips that were prone to breaking. In 1910 GE changed its basic design to a round bulb, although still with the exhaust tip. In 1916, GE introduced tungsten filaments and gave the new design the Mazda trademark. Two years later, they removed the tips, making the bulbs more fully round. In 1919 GE changed its bulb shape again, this time to the familiar cone resembling a candle flame. This bulb shape remained in use until the late 1970s and more recently has resurfaced as a "vintage" style. (Anyone interested in dating old sets of lights can consult the Old Christmas Tree Lights website, which was originally created by the brothers Bill and George Nelson.)

Just as the "typical" bulb was evolving, more decorative figural bulbs were arriving on the scene. By 1908, the Sears and Roebuck catalog featured a set of a dozen painted glass bulbs shaped like small fruits and nuts for $2.75. In 1910, an article in Scientific American described Christmas bulbs in the shape of flowers, animals, snowmen, angels, and Santa Claus. The 1919 Decorative Lamps catalog of the American Ever Ready Co. (precursor to the Eveready Battery Co.) branched out to bulbs of St. Patrick, Halloween pumpkins, clowns, and policemen. Austria, Germany, and Japan became famous for exporting figural bulbs.

These novelty bulbs had their challenges. Depending on the orientation of the base, some figures hung perpetually upside down. The paint could easily flake or wear off. Some of the designs are just creepy-like the two-faced doll's head shown at top. But I would happily decorate my home with many of these antique bulbs. To me, they're warmer and more inviting than some of the brash lights of today.

A couple who collected Christmas lights and so much moreWhile researching this month's column, I stumbled upon the doll's head bulb while scrolling through the online collections of the Smithsonian Institution. I had hoped to uncover more information about the object, but the online records had limited details. I did, however, learn a few things about the donor.

The lightbulb came to the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History in 1974 through a bequest from Edith R. Meggers, who had died the previous year. Altogether, Meggers donated more than 800 objects , including badges and pins, dollhouse furniture, toys and games, calculators, typewriters, and electrical insulators. Meggers shared a passion for travel and collecting with her husband, William. They displayed their treasures in their home, which they dubbed "The Meggers Museum of Technology." Their collecting habits were well known in the Washington, D.C., area, and the Washington Post ran a feature article on them in 1941 with the subheading "They Collect Just About Anything You Can Name."

Edith Meggers donated more than 800 objects , including badges and pins, dollhouse furniture, toys and games, calculators, typewriters, and electrical insulators.

Collecting was just a hobby, though. Edith Meggers worked in the Building Technology Division of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS), which is where she met her husband; they married in 1920. Although Edith's name might not be familiar to Spectrum readers, her husband's may be. William F. Meggers was the chief of the Spectroscopy Section at NBS.

When William Meggers first came to NBS, spectroscopy was still a developing technique, and so he spent the first few years studying the process. His early papers examined the influence of the physical condition of samples, the method of excitation, and the apparatus used to obtain and record the spectral data. In 1922, Meggers published an influential paper (along with C.C. Kiess and F.J. Stimpson) on the use of spectrography in chemical analysis. Over his long career, he studied the spectra of 50 elements, establishing international standards for measurement.

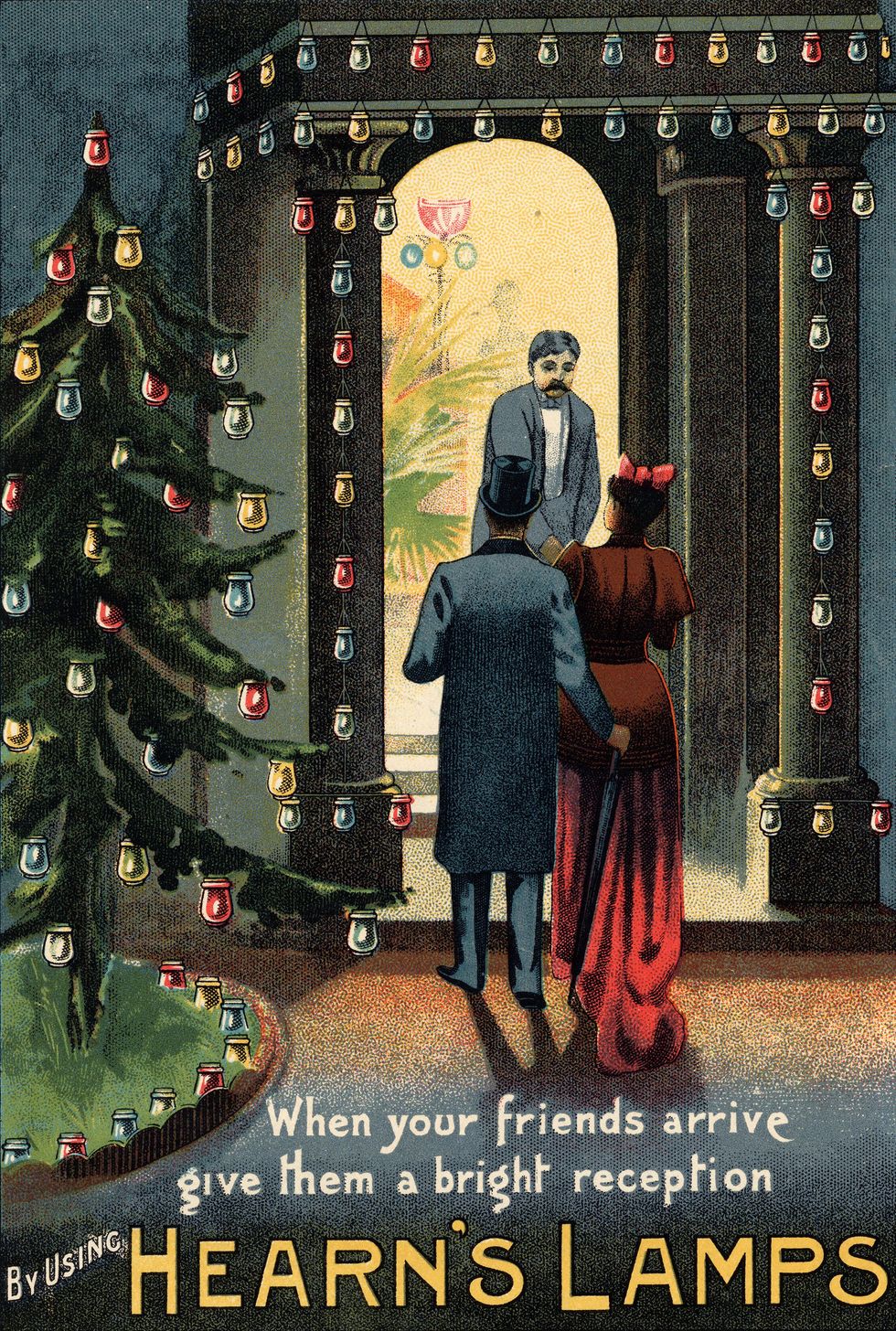

How a museum curator curates This 1895 ad equates electric lights with wealth and conviviality. History of Advertising Trust/Heritage Images/Getty Images

This 1895 ad equates electric lights with wealth and conviviality. History of Advertising Trust/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Of course, being a famous physicist and an avid collector doesn't fully explain how the Meggers' Christmas lights and other objects found their way to the Smithsonian. The bequest of Edith Meggers was handled by her attorney and involved a dozen different curators because the collection spanned several divisions. Unfortunately, the donation records are sealed to researchers until 2032. But it is possible that Edith and Bill's collecting habits wore off on their daughter, Betty Jane Meggers. She earned her Ph.D. in archaeology from Columbia University in 1952 with a dissertation focusing on Marajo Island, Brazil. She enjoyed a long career with the Smithsonian Institution, where she was the director of the Latin American Archaeology Program at the National Museum of Natural History at the time of her death in 2012. So Betty Jane would have known the process for donating objects of value.

As a former curator with the Smithsonian, I remember getting phone calls and emails from potential donors who were cleaning out basements and attics and wondered if their mementos were worthy of inclusion in a national museum collection. Often, curators have to say no due to space limitations. However, if the object's provenance is well documented and the item is in good condition, curators may ask for more information, especially if there is a good story attached to it.

I found it fascinating to go down the rabbit hole of the history of the electrification of Christmas.

The story is key because curators will have to justify the acquisition, explaining how the object will fit into the museum's collection plan and how it will be used in exhibits, educational programming, or research projects. Having additional contextual materials, such as photos or user manuals, helps make the case for the object's worthiness.

Another tip for donating is to make sure you match the item to the proper museum, library, or archive. A national museum might not be the right fit (and even if it's accepted, your item is much more likely to be put into storage and never go on display). Consider regional and local museums as well as specialized institutions. For example, after my father died, I sent a photo of some of his engineering books to Jason Dean, vice president for special collections at the Linda Hall Library, in Kansas City, Mo. The Linda Hall is an independent research library that specializes in science, technology, and engineering. Dean took some of the books, and I had to pay shipping, but I am happy that they found a new home.

I'm one of those people who love learning through objects, and I enjoy trying to figure out what stories these old, everyday items can tell. Although I wish I could have learned more about the figurine light that Edith Meggers gifted the National Museum of American History, I found it fascinating to go down the rabbit hole of the history of the electrification of Christmas and to learn more about Edith and her family. Perhaps someday something of mine will end up in a museum-but my curatorial opinion is that the story isn't there yet.

Part of a continuing series looking at photographs of historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the December 2021 print issue as "It's a Wonderful Light."