Part 3: How will agents grow and innovate their businesses?

The NHL draft has passed and the league is on the cusp of its annual pandemonium of free-agent signings. There's no time in the calendar when player agents are busier or more in the spotlight. But agents are more than money men. In this three-part series, John Matisz examines every aspect of the agent's professional life.

All three parts are available to be read now. Part 1 explores the dual tracks of acquiring and keeping clients. Part 2 covers a day in the life of Edmonton-based agent Gerry Johannson. Part 3 below looks at the future of the business.

The player agent has been part of the fabric of the NHL since now-disgraced Alan Eagleson negotiated a two-year, $70,000 contract for junior phenom Bobby Orr in 1966.

There are currently 190 NHLPA-certified agents (187 of whom are men) and an additional 200-plus uncertified pseudo-agents spread across North America. Just like the game itself, the player representation business has grown exponentially over the past 56 years.

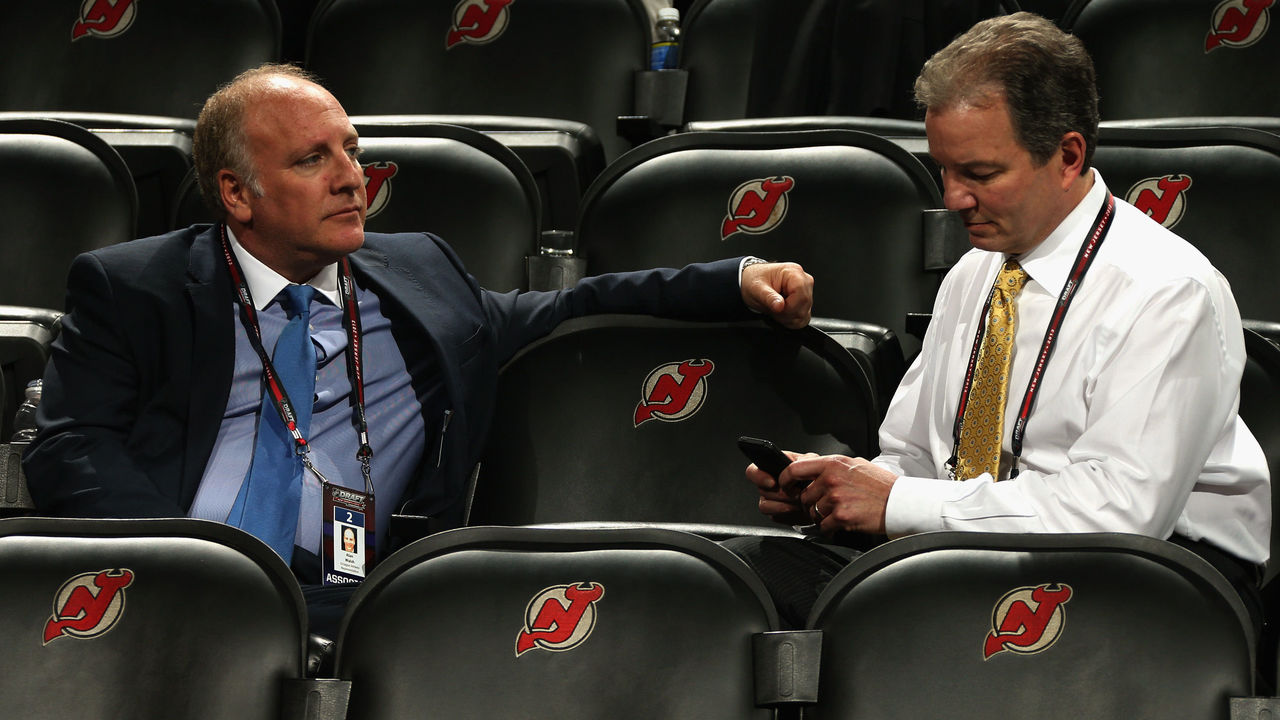

NHL agent Allan Walsh talks with executive Ray Shero. Dave Sandford / Getty Images

NHL agent Allan Walsh talks with executive Ray Shero. Dave Sandford / Getty ImagesIt's become standard practice for agencies to cater to players' every need, offering services ranging from financial management to on-ice development. It's rare that a firm doesn't bill itself as "full-service" or a "boutique" (or both) in promotional material.

"Everyone looks at an agent and they talk about negotiating contracts. That is the tip of the iceberg, the part you can see. There's a huge f------ piece under the water that you can't see," said veteran agent Rick Curran, who arrived on the scene in 1978 and now is co-head of the ORR agency.

As the business has matured, agents have continued to find new ways to serve their clients and set themselves apart. Many have become NHL front-office executives, while a few have been ditched by players happy to represent themselves.

Differentiating factorsOne agent with 20 years of experience remarked it's virtually impossible to revolutionize the player representation business when its main revenue stream remains commission earned off NHL contracts. Negotiate well, then figure out how to add value elsewhere.

That said, the agent acknowledges that standing out from the crowd in some way is imperative to any representative or agency trying to attract and retain NHL clients.

Cases in point: Allan Walsh of Octagon Hockey has built up a massive audience online by frequently promoting his clients' on-ice exploits and taking NHL commissioner Gary Bettman to task; Kurt Overhardt of KO Sports has sparked industry-wide conversation by lobbying for what he's called an "Exception Player Rule"; Ian Pulver of Will Sports Group has a unique perspective to offer as a former longtime NHLPA lawyer.

Raze Sports, which acquired Uptown Sports earlier this year, says it's taking a "very pragmatic" approach to the player-agent relationship. "What do you need to advance your career? That's what we want to provide to you. What is it?" is the first question president Ritch Winter and partner Todd Reynolds ask new clients.

Raze's approach is built upon four pillars: goal setting, visualization techniques, personal coaching, and stick calibration. The first three deal with mental resilience and marrying a player's long-term goals with daily high performance. Former NHLers like Marian Hossa, Jeremy Roenick, and Dominik Hasek are paired with current pros to help guide them through scoring slumps and other obstacles unique to the pro grind.

As for the fourth pillar: "I've worked with PGA golfers," Winter said, "and they would go to the moon to have a slight adjustment made to the head of their club. So, what have you done about your hockey stick? Are you using the right lie, the right flex, the right curve?"

Raze's clients also go through a "brand discovery workshop," which often includes developing a strategy for the Web 3.0 world of cryptocurrency, NFTs, and the like.

Alterno Management will launch an NFT-powered community later this summer. Fans who pay to join the "SINBIN" club will be assigned to a virtual NHL city where an Alterno client plays. In that city, fans can chat with the host player - for instance, Ducks forward Isac Lundestrom in Anaheim - and attend watch parties at a private clubhouse within the metaverse. The hope is that, eventually, players and fans will begin interacting offline in the form of meet-and-greets and charity-driven events.

"It's a combination of growing fan interaction and creating knowledge and awareness for these types of Web 3.0 investments for our clients," Alterno CEO Peter Wallen said.

People gather outside the NFT.NYC conference. Noam Galai / Getty Images

People gather outside the NFT.NYC conference. Noam Galai / Getty ImagesAllain Roy, president and CEO of RSG Hockey, has considered hiring a crypto expert to educate and help players navigate the "slippery, dangerous world" that is Web 3.0.

"Guys want to hear about alternative investments. They want to hear about marijuana, esports, all of that. Players are buying land in the metaverse," said Roy, who won a silver medal at the 1994 Olympics as Team Canada's backup goalie. "You have to be able to have those conversations with players and understand what they're telling you. When I go to dinner with these 22-, 23-year-olds, that's what they're talking about. If you, as an agent, are not somewhat knowledgeable, they're going to go somewhere else."

In general, Roy believes agents must adjust to this generation's business-savvy player.

"The smart players are asking the right questions: 'What are you bringing to the table?'" Roy said. "My solution is to give them more, whether it's marketing, protecting them legally, data analytics, player development. There's so many different ways." (RSG is working on a "big biometric, epigenetic application science project," Roy says, though he declined to share details since it's in the beta stage and he wants to be the first to market.)

Player development has been a staple of the business for at least a decade, with agencies holding client-only camps, bringing on high-end skills coaches, and providing video analysis. But the sheer amount of resources being dedicated to that portion of the yearly budget has exploded over the past few years, according to agents from several groups.

NHL agent Ray Petkau on the ice with goalie James Reimer. Handout / Alpha Hockey

NHL agent Ray Petkau on the ice with goalie James Reimer. Handout / Alpha HockeyRay Petkau, who runs Alpha Hockey, has carved out a niche by offering a year-round goalie-specific program called NET360. Goalie guru Adam Francilia, Alpha's director of player development, is in constant contact with clients during the season, and every summer the firm hosts a week-long goalie retreat and think tank in British Columbia.

"Some automotive shops will work on any makes that come in, and others may specialize in Mercedes Benz. So if you have a Mercedes Benz, you might go there instead," Petkau said. "That's how some goalies look at it. We can do some things that maybe other agencies can't. Or maybe they can but it's more difficult to pull off."

The newest agency on the scene, the month-old CAL Sports Management, has put player development at the core of its brand. One co-founder, lawyer Joe Caligiuri, handles the suit-and-tie duties of representing players, and the other, former NHLer Matt Calvert, dives deep into on-ice performance in order to "hit them in two different ways."

"One thing I thought I was great at in my career was developing relationships with my teammates," said Calvert, who played 600 NHL games split between the Columbus Blue Jackets and Colorado Avalanche. "Being honest with them but also knowing how to pump them up and help get them past the hurdles of pro hockey - that's what I really want to do with clients. There's so much talent these days, especially in junior hockey."

Quartexx Management's NHL client list runs 54 names deep, placing them fifth among all agencies in active contracts on the PuckPedia leaderboard. The firm, which was founded by Canadian billionaire Lino Saputo Jr. and the product of high-profile mergers in 2016 and 2019, owns a state-of-the-art facility in Montreal. At Hockey Etcetera, clients have priority access to a three-on-three ice rink, fully equipped gym, cold tub, osteopathy and acupuncture treatment, and lounge area featuring a pool, ping pong, and food.

The facility isn't used exclusively by Quartexx clients but is certainly designed for them.

"It's expensive and it eats into the profit margins, which is why most agencies aren't getting into it," COO Giordano Saputo said. But, the agent added, "We're really building our business model off being a one-stop shop, all-encompassing agency where we can take care of all aspects of life." That includes in-house marketing and financial management. (Quartexx is looking to build a second facility in Vaughan, Ontario.)

Quartexx's Hockey Etcetera 3-on-3 pad in Montreal. Handout / Quartexx Hockey

Quartexx's Hockey Etcetera 3-on-3 pad in Montreal. Handout / Quartexx HockeyIn late June, Quartexx announced Ottawa Senators assistant general manager Peter MacTavish had joined the agency as a director, senior counsel, and agent. A few days later, Winnipeg Jets amateur scout Max Giese started at CAA Sports. While the player representation business and NHL front offices have shared off-ice talent for years, multiple sources noted the pipeline has been especially active in 2022. Back in January, former Quartexx agent Kent Hughes became general manager of the Montreal Canadiens. A week later, another ex-agent, Emilie Castonguay, was hired by the Vancouver Canucks to be an assistant GM.

"Teams are smart to talk to agents for hockey operations roles. We touch every aspect of the business," Roy said. "On top of that, if you're a seasoned agent, you're already managing people. You have a staff working under you, you have a lot of different players to service and your finger on the pulse of pretty much the whole hockey world because of how many people you're connected with and the knowledge you have of young players coming up."

Existential questionsThe bulk of agencies, from giants like Newport to smaller firms like WD Sports & Entertainment, recruit players who aspire to play in the NHL. The business model hinges on clients earning a living in the sport, whether it's in North America or overseas.

There's a much smaller segment specializing in clients whose chances of appearing in even one pro game are microscopic. Often in these deals, a player pays an adviser a few thousand dollars to help him land a roster spot on a junior or college team - and that's it.

"It's a disturbing trend because I don't understand the value," one NHL agent said.

At the other end of the spectrum: established NHL players ignoring a long line of prolific agents to represent themselves during contract negotiations. Veterans Drew Doughty, Nicklas Backstrom, and Alex Ovechkin have hashed out at least one contract without a certified agent in the room. These players will usually lean on a lawyer for legal assistance and reach out to staff members at the NHLPA for marketplace analysis.

Drew Doughty during a March 2022 game. Icon Sportswire / Getty Images

Drew Doughty during a March 2022 game. Icon Sportswire / Getty ImagesDoughty negotiated an eight-year, $88-million extension with the Los Angeles Kings in 2018. Shortly after the deal was announced, Doughty told The Athletic that he felt Newport's Mark Guy had "done an amazing job" for him in the past and would be a lifelong friend. However, he continued, "if you punch the numbers in and they take 3%, the amount of money that I saved doing the deal for myself is ridiculous." (For context, 3% of $88 million is $2.64 million.)

Self-negotiating an extension, like Backstrom and Ovechkin also did in Washington, is one thing; the player and GM know each other extremely well. When journeyman Anthony Duclair tested the free-agent market without an agent in 2020, though, eyebrows were raised across the industry.

After relaying his "side of the story" to multiple GMs, Duclair inked a one-year deal with the Florida Panthers. "I just wanted to take ownership of my own life and my career. I wanted to learn the business side of the game," the forward told Sportsnet. When you have an agent, Duclair said, "sometimes they shield you from the truth a little bit."

This small group of players representing themselves isn't shaking the business to its core. It's happened in the past and it'll happen again. Yet, given how many services agents provide to today's NHLers, most crucially, advocacy after an injury, benching, or other tension point between player and team, it is a curious blip on the radar to monitor.

"I wish all players would just be more demanding as clients," said an NHL assistant GM. "You can have an agent and be really demanding. There's nothing wrong with that."

Meanwhile, a veteran NHLer calls Duclair's decision to represent himself "ballsy." Duclair wanted to take full control of the situation and it didn't blow up in his face.

"I think it crosses every player's mind," the veteran said. "Could you do it on your own?"

Part 1: Being an agent is far more complicated than negotiating contracts

Part 2: The inner workings of a business day at a prominent agency

John Matisz is theScore's senior NHL writer. Follow John on Twitter (@MatiszJohn) or contact him via email (john.matisz@thescore.com).

Copyright (C) 2022 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.