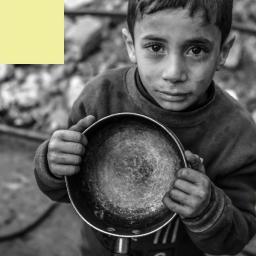

No Safe Place in Gaza

Humanitarian aid into Gaza faces near insurmountable challenges," World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said on Wednesday at a news conference in Geneva. Amed Khan, a humanitarian relief activist who has helped deliver aid in war zones around the world, said the refugee situation in Gaza is unlike any other: There is no safe place to go." Khan joins Ryan Grim on Deconstructed this week to discuss the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Gaza and why President Joe Biden's unwavering support for Israel in the war motivated him to quit the Biden Victory Fund National Finance Committee.

Ryan Grim: Welcome back to Deconstructed for 2024, I'm Ryan Grim. And, unfortunately, we're kicking this year off with a close look at the deteriorating humanitarian situation in Gaza caused by Israel's strategy of restricting food, fuel, water, and medicine.

Hind Khoudary - a Palestinian journalist who wrote for us recently - reports that grocery stores are now effectively barren, and pharmacists are telling her that drugstores will be empty very soon. She just posted on social media that she woke up with an extreme sore throat. It has no way of getting antibiotics. Those types of infections, if not treated, can be deadly in otherwise healthy people. There were around 2.3 million people in Gaza at the start of this war, and a shocking 1 percent of them have now been killed, with the rest at serious risk.

We're joined again today by humanitarian relief activist Amed Khan, who last year joined us from the front lines in Ukraine. After the Gaza war broke out, he traveled to Rafah to help organize relief efforts, and also tried to help evacuate dual citizens from Gaza. He's also been a major donor to Biden and to Democrats over the years, and recently made news by announcing he's splitting from Biden's finance team over Biden's unconditional support for Israel's war.

Amed, thanks so much for joining me again here.

Amed Khan: Thanks, Ryan. It's nice to be with you, I appreciate it.

RG: And so, can you set the context for people with regard to what you've seen throughout your career? Can you talk a little bit about the different hotspots, different crisis situations that you've been on the ground for over the years, so that people have an idea, when you talk about what you've seen in this crisis, how that compares?

AK: Well, I've seen a few people have spoken about their experiences and, generally, I think all of us don't like to talk about them, because they bring up a lot of bad memories. But, for context, I started in international humanitarian relief in the Rwandan refugee camps, where we had a million refugees, in my early 20s. I left a job in D.C. and the Clinton administration to essentially work and live in the middle of the Rwandan camps for about 18 months.

And, since that time, I have delivered humanitarian assistance into just about every single combat zone that's existed. So, Somalia, Yemen, Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Sudan, Congo. You name it, I've been right in the middle of whatever war was being waged, delivering whatever I could get in.

RG: And so, after October 7th, you traveled to Egypt, to the Rafah border crossing. What was the situation then that you encountered?

AK: Well, as happens when a war breaks out, it's sort of complete chaos, and uncontrolled chaos. But, in this case, since some of the borders are with Israel, those were closed, and all the borders are completely controlled, which is different than in any other refugee situation I worked with. With regard to Ukraine, you could get out to Poland, you could get out to Slovakia, Romania. It was completely chaotic on February 24th, 25th, 26th, but people were able to get out.

In the Gaza situation, the borders were all completely sealed in the first few days, so you sort of felt completely helpless trying to help people either get out, or get medicine and food in.

RG: What insight did you have then into both the negotiations to try to get a pause in the fighting, so that, in those early days, you could get some hostages that started to be starting to be released, but also citizens of other countries evacuating from Gaza? You had Ukrainians, Americans. I noticed that Israel in the very beginning was most insistent on not allowing Brazilians and Irish people to leave, which seemed to be kind of specific, related to Lulu's criticism, and also the Irish support for the Palestinian effort.

But what was your involvement with trying to get dual Palestinian Ukrainians or Palestinian Americans, or others out of Gaza?

AK: Well, I started with Americans, which is what I usually do as an American. And you'd of course love to help everybody, but you sort of think, oh, this action has been initiated by an American backed operation, so maybe people will care about the Americans, so maybe it'll be easier. But it wasn't.

RG: Why not? Like, what happened? What was it like to try to get them out?

AK: I think nobody cared, right? I just think probably middle-level people in the State Department really, really cared, but I don't think anyone at the top made it a priority to say, hey, we have these many Americans, and we need them out today. Because the first ones, family members with American passports that I was involved with, left, I think, 30 days in. So that means, for 30 days, these children and women were subject to... Originally I said indiscriminate bombing, but then I decided it wasn't really indiscriminate bombing, it was actually targeted bombing at civilians.

RG: Right. They weren't randomly hitting farmland or streets. They tended to hit residential buildings, which implied some discrimination. Yeah.

AK: When I say this, it's my opinion, and it doesn't hold up anywhere, but I have 25 years of experience working with armies, you know? The last two years I've been alongside the Ukrainian army, so I know what goes into targeting. I know how many checks there are before you hit fire, whether it's an F-16, or an M109 Paladin howitzer, or whatever it is, you know? Like HIMARS in Ukraine. And then the U.S. army in Iraq, how many checks? Are there any civilians, are there any civilians?

So it was very clear to me that, let's say, the four or five hundred, six hundred Gazan families, whether they were Ukrainian dual nationals, or ethnic Ukrainians, or American dual nationals, they were all in jeopardy no matter where they were. So, there was a certain level of desperation that I've actually never felt before, a certain level of helplessness that I've never felt before, no matter where I've been, and no matter how horrible it was, because I've never seen a situation...

And even from the Rafah crossing, from the Egyptian side, you can see F-16s circling, and you just don't know where the bomb's going to fall, right? Like, at that point we weren't sure what was actually dropping, and then you start to find out that it's actually giant dumb bombs, right? Which the blast radius on those are unimaginable. And then, as you went on and on, it becomes more desperate.

RG: What made it the most harrowing situation that you'd seen? Like, what are the key differences that you identified?

AK: For the purposes of this, we can compare it to Ukraine, a giant country perhaps the size of Texas. And then Gaza, the size of Philadelphia or Las Vegas. And no way out, right? Like, there's the sea on one side, and all the borders are sealed, so you actually can't escape. And then when you start to see the bombing, you see that it's everywhere, right?

So then, you're, let's say, a woman with three small children in tow. Your husband stays back in Gaza City because he's volunteering at the hospital - let's say this is October - and you're just wandering around down the streets looking for somewhere to go. That I've literally never seen before, because there was always somewhere to go, no matter how horrible the refugee situation was, or the war situation. And this is the first time where there was no - and there is to this day, which I find just mind boggling - there is no safe place to go. Nowhere.

I was just on the phone with one of my partners in Gaza who delivers food and medicine, a Gazan resident. He said, two million people right now are using one street. Like, you can't begin to imagine what that means, right? And they're all together in Zawaida or Rafah. You know, a very small area. So, it's not the size of Philadelphia now; it's less than the size of downtown Manhattan, basically, with two million people.

And so, a number of reasons: no access to food, no access to water, no access to medicine, your kid has a headache, you can't get an aspirin. So, a variety of these reasons. But I think, really, the scariest thing is watching the planes overhead, knowing you have no control over where that bomb's going to land. You have no control, no matter of skill, no matter how skilled you are as a survivor, you can't protect against that. There's nothing you can do to protect against that.

Let's say people that I've known and I've been involved with since before October 7th, a solid number of them - and I don't know the exact number - are not with us anymore. So, when I see this thing about human shields and all this other kind of crazy language coming out of the State Department and the White House, about minimizing civilian casualties, and increasing aid... The aid is nonsense. Like, there is nothing coming in of any value, it literally barely scratches the surface of what's needed. And the limiting civilian casualties? The numbers speak for themselves. There's literally not a... What conversation is there?

RG: The State Department often says there are about 200 trucks a day going in. Do you think that's accurate? And what would need to go in to remotely meet the need?

AK: Well, we know exactly how many trucks go in, and it's between 0 and 200. This is from my information, it mostly depends on the Israelis, right? So, what would need to go in would be a thousand, at a minimum, and the reality is, of those, let's say you have a good day, and it's 200. Some of the stuff that's coming in you don't really need, like biscuits. Like, that's great, high-energy biscuits, fantastic. But if your kid has a headache and he's screaming or she's screaming, you need aspirin. So, thanks for the biscuits, but ...

So, I have no understanding. Like, the Israelis sort of are blaming the U.N., the U.N.'s blaming the Israelis, the Egyptians are blaming everybody. I mean, I don't think there are any great heroes in this situation, but the bottom line is, none of it is productive for the people. And it doesn't seem like it's really that important to the United States government, because that, ultimately, is the most powerful entity out of all these entities. So, if they really wanted civilian casualties to ... I don't know what they say. Minimize? I mean, it's a horror, it's a horror.

Like, I've been in Ukraine, and anytime a child is killed in a sort of Russian bombing, I go there, and you're just horrified. It's one child. And now to think about Gaza, and the number is clearly over 8,000, I think it's higher. And I personally know of all sorts of children ... Their crime was sitting in their apartment building. Their apartment building's not on any tunnel or connected to anything, and not near anything, and I have all the evidence. I think in the future - it's not going to help - but in the future, I think all this will be studied, and it'll come out, and hopefully there will be enough of us working on this that holds every single person accountable.

But, from my perspective, if I know what's going on, it seems to me the U.S. government would know what's going on. So, that's my reason for just being completely disgusted.

RG: You were telling me before this call, you're joining us from Greece, because you had set up an NGO there that had helped get Afghan refugees out, you're checking in on them now. I'm curious, how many families did you successfully get out of Gaza? What was it that finally ... Was it just time and pressure that, finally, a month later got a couple of families out with American passports? Or, how many are still stranded? What is the situation now?

AK: I don't have the exact numbers, but let's say I know somewhere between 50 and a hundred American passport holders who are still inside Gaza.

There are a number of people, entities, members of Congress, the different organizations that work on these issues, who are all sort of lobbying. And the truth is that the United States embassy in Cairo, and the emergency consular teams do a terrific job. What it comes down to is if you have a family, and let's say you are the U.S. passport holder, and your wife doesn't have a U.S. passport, and your children don't have U.S. passports, you're not going anywhere, right? You're not leaving. So, you go through this process of contacting the U.S. government and saying, look, I have these people, and can you help? And you get to the border, and then consular officials will take care of you.

Now, some countries don't have the ability to do that. In terms of dual nationals, they're clearly hundreds, if not, like, in the lower thousands, who are still stuck in Gaza, because of this situation with not wanting to separate the family. Very often the husband will stay behind, but you have this situation... For example, an ethnic Ukrainian family that I'm trying to help, the two children are out but the mother isn't, and she's actually born in Ukraine. She hasn't been on the evacuation list, so the two children are, so you're just trying to figure out who to call and how to get it.

But, essentially, a hundred days in, it's still not working. It's not working.

RG: And so, correct me if I'm wrong, but because you have so much experience on the ground over the years, and you also have built so many connections at the high levels of the Democratic Party through fundraising and donations, I would imagine that when situations break out, that there are a lot of people in Washington - let's say, in Ukraine - they know you've been there for a couple years on and off, that reach out and want to get your take to see how things are going on the ground.

Is that happening with regard to Gaza? Are people in Washington asking for your take on this? And when you came back to D.C., what were the questions like? What's it like to go back and forth between these worlds?

AK: Well, I don't think I'm going back anytime soon. It's not good. Yeah. Nobody's asking me for my opinion on anything.

RG: You're not going back to Washington anytime soon, you mean?

AK: Yeah. Yeah. No, absolutely not. Yeah. Nobody's interested in what I have to say, obviously, for obvious reasons, right? Like, they've got blinders on, and they're living in some kind of alternate reality that we'll prove in the future was inexplicable.

It's very, very clear. It was very clear to me from the beginning that the Israeli operation was based on clearing out Gaza. And they say this, themselves. I mean, they say it out loud, right? And it's sort of ludicrous that the language coming out of Washington is then, that's very irresponsible, we don't approve of that."

It's like, literally, the Israeli government is telling you what they're doing. Any number of ministers, any number of members of the Knesset, opinion makers. They say what they're doing, they say they want to reduce the population of Gaza, and they're actually doing it. Because if you look at the bombing map, you try and find an empty space where there wasn't a bomb in all of Gaza.

And then, the reaction from the U.S. government is, yeah, it's irresponsible. Irresponsible. Irresponsible? The children are dead, they're not coming back. Five-year-olds, six-year-olds, seven-year-olds, eight-year-olds. They're guilty of nothing.

I'd love to have a truth commission someday and actually ask these people what they were doing.

RG: Is this lack of interest in your perspective different than Ukraine? Like, have people been, over the last couple years, have you had U.S. policymakers ask for your take on Ukraine? Or do they have so many eyes there that they're like, we got this covered?

AK: No, I've definitely been asked by various agencies and elected representatives. Because I see stuff on the front line that they don't really have access to. And so, I've definitely been asked for my opinion.

RG: So, there is a difference between these two.

AK: Yeah, there's definitely a difference, there's absolutely a difference. And it's actually very, very startling, unsettling, disappointing, upsetting. I'm not shocked, but it's very sad.

RG: So, what got you to the decision of, I'm off the Biden train?"

AK: Oh, it's very easy. Genocide, ethnic cleansing, whatever you want to call it. I mean, I'm not a legal scholar, so I don't know what the difference is.

There's thousands and thousands and thousands of innocent civilians who are dead. There are many thousands who are stuck under rubble, and we still don't know how many, because there are no emergency services. There are many thousands who are injured, kids who have lost their arms, their legs, their eyes.

So that wasn't, it wasn't even a question. Just, sort of like, ethnic cleansing is where I get off the bus, right? It's just not ... You can't be a part of that. And I come at this as a humanitarian. I'm basically a card-carrying human being, this is what I do. No matter what it is, and no matter where it is, I will try to help innocent civilians no matter where they are.

I crossed ISIS to go to the Chaldean Catholic communities in Iraq to rebuild their homes. I went through the Russian lines to rescue Holocaust survivors in Ukraine. I will do anything, anywhere, for anyone that needs it, and that's my thing, right? So, how could I be a part of this?

Now, I'm not saying this should apply to everyone. If this isn't what I did, maybe I wouldn't feel so strongly. But if I say my life is dedicated to humanitarian action, then it would be kind of strange to be a supporter of what's happening in Gaza.

RG: Now, the counter argument that you see to getting off the bus is that the other bus is driven by Donald Trump. So, how did you think through that question as you were coming to that decision?

AK: There are 350 million Americans, there's 200-and-some million that can vote. And politics isn't really what I do. I like to be supportive of people I share values with, but I don't share this value. So, it's not ... You know, whatever happens, happens, and whatever happens with the United States government, it's probably what we deserve.

And do I think, like ... I don't really give it much thought, but I kind of find that, if I'm interested in these issues, I don't know how it could be worse under Trump. So, like, I don't know. He was president for four years. He didn't really invade anywhere. He says there were no wars, and then there weren't. You know, he's probably right.

So, it's not something I can think about today, when what I deal with on a daily basis are ... You know, General Sherman had this quote about, you know, that war is hell quote. But, before he says war is hell," he said something like, it's always the ones who never fired a shot or never heard the shrieks and groans of the wounded who are always rip-roaring to go to war. And I hear shrieks and groans every single day of my life, and that's what I'm driven by. And so, I can't think about the U.S. election a year from now as something that's going to drive my decision-making.

RG: You're always getting reached out to, I'm sure, by Democrats. What's been their reaction to your decision? Because you're not the only one that has said that this is a line that has been crossed, but how have they handled that in Washington?

AK: I've got a lot of messages that say, I admire you, but off the record, you know? I don't think people in Washington are known for their leadership or independence or any of that stuff. I mean, look, they're just so far removed, right? Like, they're just ... We have all these people that are ten levels removed from this stuff. They're sort of living their lives, going to cocktail parties, going to whatever restaurants they like. And I live a different life.

I'm there, right in front of these people. I wake up with nightmares at night, so like, I don't know. I'm not going to judge anyone, but...

RG: You've gone back four or five times to the Rafah border since then. How have you seen it change?

AK: Well, nothing's really happening. I mean, some people leave. The official lists are done by governments through each other. The governments work together to get people on the list, and they have to be approved by the Israelis, they have to be approved by the country that's submitting them, they have to be approved by the Egyptians. And then they get out.

So, some people leave during the day, during the day, some days. And then there's lines of trucks, right? The truck line last time I was there was right before Christmas, it was probably three or four weeks. And can you imagine that relief trucks are waiting in line for three weeks? And what's in that truck is desperately needed, and...

So, I mean, nothing good is going on.

RG: Trucks just sitting there for three weeks?

AK: Sitting in line, yeah, because of the ... Everyone will give you some other story as to what it is but, essentially, it's the security process, right? The Israelis want to know what's going in, which is legitimate, but it just seems to be [that] it could be faster.

RG: The Israelis have also said, different factions of the government have said that starvation is useful to their strategy, to their policy. How much of it do you think is just the unintended consequence of legitimate security concerns, and how much of it do you think is a deliberate squeezing of the population to produce the exact crisis that you're seeing, which then forces the world to align itself with Israel's mission of emptying out Gaza?

AK: Look, bombing and starvation have never worked, and it's clearly a strategy, and it's clearly a strategy that some of the Israeli governments are pursuing, and so it has to be some percentage of... Let's say Wednesday there's 150 trucks, and it's not 1,000, and some percentage of that 850 is willful, and some of it is just incompetence or whatever. But yeah. Absolutely, it's a combination of the two, and none of it is good.

Look, it's not getting better, so what is everybody doing? Like, the Secretary of State multiple times goes on these meetings, and you see, what's the purpose of the meeting? The purpose of the meeting is to minimize civilian casualty, increase aid. The aid hasn't increased. This is a recurring theme since mid to late October, right? Like, the aid has not increased, it just never increased, so someone clearly doesn't really care, right? So, starvation has to be a part of that.

And I've said from the beginning: bombing and starvation have never worked, they've just never worked. But here we are, trying bombing and starvation again.

RG: Earlier you talked about how Israel blames the U.N., and the U.N. is pointing the finger at Israel. The U.S. has, in that dispute, sided with Israel, that was one of the main concessions they got from one of those U.N. resolutions, was to strip out any role for the U.N. in getting humanitarian aid in.

What is behind that dispute? Why is Israel so hostile to the idea of the U.N. playing a role in getting humanitarian relief in?

AK: Well, that's not my area of expertise, but it seems like they've never been happy with the U.N. since 1948. They got the original vote, but they haven't gotten too many votes since then, so they don't trust any of the U.N. agencies. They don't think that any of the U.N. agencies are fair players or fair actors. They often paint the U.N. agencies as incompetent and corrupt, etcetera, so there's no love lost there.

But, again, that's politics stuff. That's really not my thing. My thing is, does little Joanna have enough to eat today? And no, she doesn't. And so, you know, whoever's at fault, we just need to do some kind of audit. Like, OK, who could influence this, and what exactly are they doing right now?

So, for me it all comes back to the U.S. government because, you know, I'm not an Israeli citizen, so who am I to criticize? They're going to do what they're going to do. But now, if the U.S. government is essentially their prime sponsor, what is the U.S. government doing about this situation? And that's where I think there's a problem.

RG: One of the talking points you hear is, well, the problem is that Hamas is stealing all of the food, and the fuel, and the relief supplies. What's your response to that?

AK: What relief supplies? What relief supplies, where are they?

And then this Hamas thing ... I mean, I'm no expert on these numbers, but how many Hamas fighters are there? Thirty-thousand? I don't know. And how many are dead now?

RG: Well, they say they've killed five or 10,000 so ... Now you're down to 20,000 or so.

AK: Yeah. So then, there's 2.2 million people, 1.1 million who are children. That I know. And like, what is the process of this? How are they actually stealing it? The whole thing is easily monitored, there are Israeli drones flying everywhere, watching everything. So, it's just like one of these distraction stories to get away from, My kids don't have any food." That's really just what's happening on the ground.

RG: What's your understanding of what the security situation is becoming? By which I mean, just general levels of crime and animosity between people. Because if you... As I think about Fyre Festival, for instance, it was one of the only things that Americans might be able to understand.

AK: Oh, I don't even begin to know. I don't even know what would happen if this was happening in America. Like, people would be shooting each other and [setting themselves] on fire. But no. One way or another, Palestinians are sort of hanging in, and I don't know how.

For example, there's an ATM, there's one ATM that works in a giant area, and it takes five hours to get in your line, and the bank doesn't open. And people just wait in line, they just wait quietly in line. So, nobody cuts the line, nobody's screaming at each other. Everybody's just too tired, too hungry. too sick to start the sort of social unrest or turning on each other. Or like, in the movies where you see these mobs attacking each other and zombie movies and stuff. Like, none of that.

They're just [like] look, we want this war to end, but we're not going to turn on each other. And people just are cooperating, and trying the best they can to get through each day. Because if you're sitting there with your family, or your extended family, your whole purpose in life is to live through that day and make it to tomorrow. And maybe there will be a ceasefire tomorrow. That's what I hear on a daily basis.

RG: And some people have found some actual shelter, but a lot of them seem to be in tents or under tarps, and I'm curious what the weather has been like at night.

AK: It's getting cold, you know? It's getting cold. Not cold by northeast U.S. standards, but it's in the 40s, in the 50s and, actually, you can get frostbite with the constant exposure, even in the 40s, and even in the 50s. So, again, these are people who are used to having heat, and used to being inside and having apartments. You know, it's a dense urban environment, so this is not something that a large percent of the population has any experience with; particularly the children, of course.

And so it is miserable. The number of children that are sick, and probably will die of very treatable illnesses ... It's crazy the number of children that are at risk right now. The hunger numbers are something that don't exist anywhere else on earth. It is horrible.

And yeah, some people have moved four times, some people have moved five times, some people have moved six times. You get these messages that drop from the sky that says, move here and move there, and you get bombed there. And so, a lot of people at this point are just tired of moving, and not moving anywhere else. Like, we're not moving anywhere else.

And then, other people, if you have some money, you are told to move somewhere, you literally go and buy a tent, you know? Because there's not tents for everybody. So, most everyone has sort of worked through their entire life savings. Their homes are destroyed; I saw a quote yesterday, which I think I talked to you about, about people returning to their homes.

RG: Yeah, Matt Miller.

AK: And I said, what homes? There's no shortage of people that I know ... Their homes don't exist anymore I would say, of the people that I'm in constant contact with, 90 percent, easily. And this is hundreds of people. Their homes do not exist. They're uninhabitable, unlivable, so even if it was safe in whatever area they live in, where they're from, there's no way to move back.

And then you're constantly just trying to struggle. You're hoping you can stay where you are for tonight, and you're hoping tomorrow you don't need to move, whether you're told by the Israelis to move, or whether the rooms you're staying with are overcrowded and they can't actually sustain having you in your family.

It's actually something I've never, ever experienced, witnessed, and I hope to never experience or witness again, you know? I took never again" very seriously as a child, and I think that's why I've gone to all these places I've gone over my life. But this, what we're seeing here is... There are no words really for it.

RG: Hind - the reporter that I mentioned at the very top - her father built their home, she sent me a photo of it. This lovely place, a little courtyard and an inground pool. It's been completely leveled. Her husband had a cafe, a little seaside cafe, that's also been completely leveled.

So, when Matt Miller said that, as well - you know, we're encouraging Israel to let people go back to their homes - I had the same thought. Well, that would be nice. How is Hind going to get back to her home? How's her husband going to go back to his business? Unless, all of a sudden, there's some massive influx of reconstruction. But those are new homes; that's not the home that her father built himself.

What about the water situation? Both in and out? Like, what's the sewage situation like at this point?

AK: It depends where you are. Essentially, the population is now concentrating in the west and the south. Access to clean water was really tough for a few weeks; that has improved a little bit.

RG: Is that from bottled water getting in, or is that from some of the plants moving?

AK: From bottled water getting in, and from some of the sanitation, physical plants getting back up and operational. Obviously there's no guarantees that that's the case, but right now, let's say today ... I mean, I'm not saying that it's great, but it's not the worst. Let's say it's the best of a horrible situation, and I would say, of the Western world, nobody in the Western world would be happy with the water situation today, whether it's water sanitation or access to drinking water. But it's gotten a bit better.

RG: What about fuel? Because I've wondered. You see bags of rice or other supplies that are brought in, but if you're living in a tent, it's difficult to cook. How are people preparing food? Or is it just these biscuits that are kind of glorified, or not? Anti-glorified power bars.

AK: So, there are various organizations - like Anera, and World Central Kitchen and, of course, the World Food Program - doing meals in centralized locations. You're making lentil soup - shorbat adas - for thousands of people. But on an individual basis, yeah, you're not cooking anything, because you don't have access to run the fire.

Some people who are hiding out in different areas will use wood, but it's not really for the majority of the population. It's a tough situation.

RG: As you cast your gaze forward, how do you see this ending?

AK: I really have no idea. I just kind of feel like I'm in it with the residents, just trying to get through each day. Hoping everyone makes it through each night and then seeing what will happen the next day. But I just take my cues from the various Israeli government authorities that say, this is what we want to do. And we'd like the population of Gaza to be 200,000 Palestinians, and I've thought from the beginning, that's what they're doing.

But I hope somebody stops them before that, but that's still the way we're going, right?

RG: Any plans to go back soon?

AK: Yeah, I'm looking at doing some delivery, flights of medicine, sometime in the next couple of weeks. So I hope I can go back then, back into Gaza sometime in the next couple of weeks. I'm working on that right now.

RG: If people want to help, is there anything they can do?

AK: I mean, there are great organizations to donate to. The Palestinian Children's Relief Fund is great, PCRF. Anera is great, A-N-E-R-A. If anyone was interested in the day-to-day, they can get ahold of me easily, maybe through you or something.

RG: Sure.

AK: Yeah. I mean, there's tons of stuff you can do. For example, I support, I don't know, a few hundred American passport holders who are in Cairo with hotels, apartments, food, while they work on their paperwork. Like, let's say a family who has one passport holder, and they have to fill out sponsorship forms to get to the U.S. for the rest of their family, like their kids. It's immediate family, so usually it's a wife and children, a mother and children or sometimes the husband, if he was a U.S. passport holder.

So, there's no shortage of things people can do to help, and help people stay alive, and I'm happy to talk to anyone about it.

RG: I should know this, but how did you originally make your money, and what made you decide to dedicate your life to giving it away and helping other people?

AK: Well, I didn't make too much, so I don't actually own anything, which is kind of weird. I don't have any of the larger ... I don't own any boats, or mountain houses, or beach houses, or any of that stuff. But this is what I wanted to do, right?

So, when I went to Rwanda, I worked for the International Rescue Committee, which is a great relief organization founded by Einstein, based in New York. But when I left there, I said, you know, I want to do this on my own, but like, how do you do that? You probably need to make some money.

So, literally, I just made some investments, which I always did as a hobby, from the time I was a kid growing up in New York. And it's really not that tough. Like, so...

RG: Piece of cake.

AK: No, it's really not that tough. I don't know, these people that rule us, the hedge funds and the private equity and all that, they think they're all geniuses. But if you're good in finance and numbers, it's really not that tough to make decent investments, you know?

So, I was basically just kind of speculating on startups and stuff like that, and I did it a few times, and did enough, did well, and did okay. It's not something I spent too much time on.

But yeah. If you limit your expenses, you can do really well. I mean, I don't stay in fancy hotels. Maybe in my next life I could come back and do that stuff, but I'm sort of an outlier in the capitalist system, I suppose.

RG: I would say so. We really appreciate you joining us again. Thanks so much.

AK: Thanks, Ryan. I appreciate it. Thanks for all your work. You're doing a great job.

RG: Well, thank you.

That was Amed Khan, and that's our show.

Deconstructed is a production of The Intercept. This episode was produced by Laura Flynn. Our lead producer is Jose Olivares. The show is mixed by William Stanton. Legal review by David Bralow and Elizabeth Sanchez. Leonardo Faierman transcribed this episode. Our theme music was composed by Bart Warshaw. Roger Hodge is The Intercept's Editor-in-Chief. And I'm Ryan Grim, D.C. Bureau Chief of The Intercept, and the author of my new book, The Squad." Go ahead and get that if you haven't yet.

If you'd like to support our work, go to the intercept.com/give. If you haven't already, please subscribe to the show so you can hear it every week. And please go and leave us a rating or review. It helps people find the show.

If you want to give us additional feedback, or you want get in touch with Amed Khan, email me at Ryan.Grim@theintercept.com and I'll hook you up. Put Deconstructed" in the subject line, otherwise I might miss your message.

Thanks for listening. And I'll see you soon.

The post No Safe Place in Gaza appeared first on The Intercept.