Howell: As Seattle adds jobs, how are the new workers getting there?

Editor's Note: Every year, we write about newly-released Census data on commute modes in Seattle and communities across the country. In this guest post, Brock Howell dives even deeper, analyzing just Seattle's new commutes. What he finds has lessons for what the city is doing right and what we need to change in order to meet our long-term and mid-term goals.

As the fastest growing major city in America, Seattle faces significant transportation and land use challenges and opportunities.

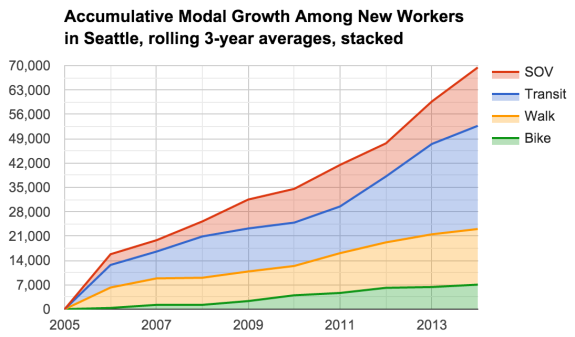

In the last five years, 70,000 new people moved to the region and the city is planning for another 120,000 to move here by 2035. Given this enormous surge of people, I wanted to see how our new residents are getting around and what that might portend for the future of walking, biking and transit.

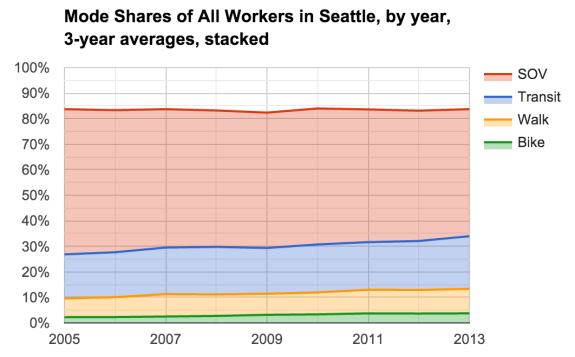

Each year the U.S. Census Bureau publishes the results of its annual American Community Survey (ACS), which among other things shows the ways workers say they commute (SOV = Single Occupancy Vehicle).

SOV = Single Occupancy Vehicle. Remaining commutes not listed include carpools, motorcycles, taxis, telecommuting.

The total rates, however, do not tell the story of the new workers. In order to do this, I analyzed the ACS data by applying all annual changes to commute mode shares strictly to the annual changes of the employment levels. Below are my twelve takeaways.

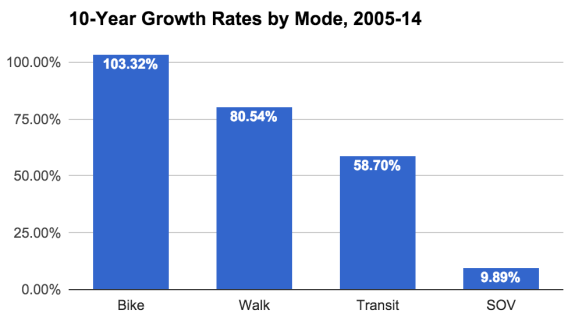

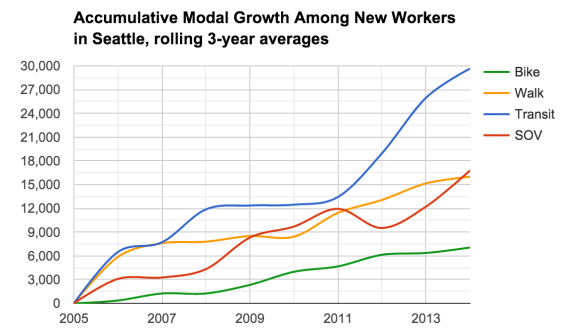

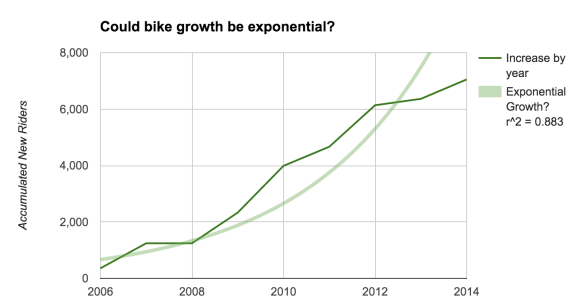

- The number of workers who bike to workdoubledin the past decade.

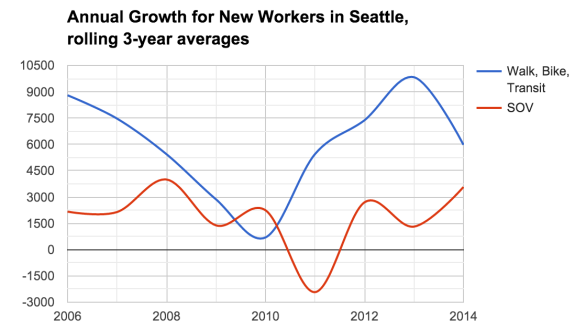

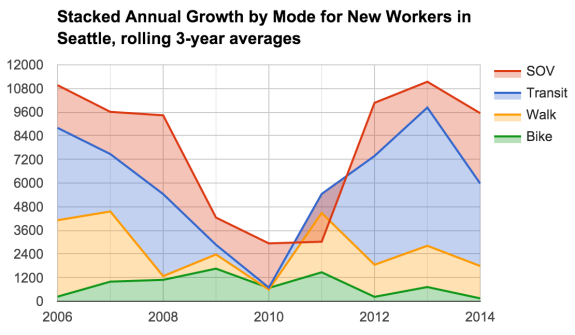

- In every year except 2011, more new workers chose to commute by walking, biking and transit than by driving a single-occupancy vehicle.From 2005 to 2014, 66 percent of new workers walked, biked, or rode transit to work, while only 21 percent drove SOVs. By comparison, the entire workforce has a 50 percent SOV commute mode share.

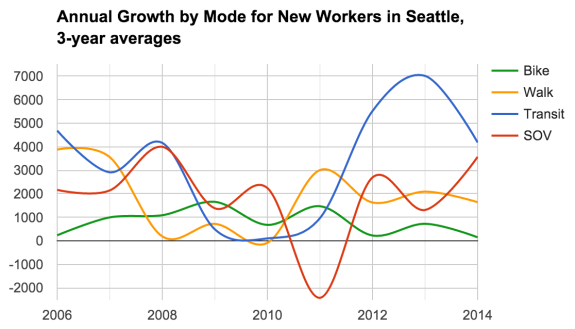

- Once the recession ended and employers started hiring, new workers took to transit at an unprecedented level. Central Link light rail opened in 2009, with its first year of full operation in 2010, the low-point of the recession. Once the recession ended, our investment in Sound Transit paid off. From 2012-14, 58 percent of new workers chose transit.

- New workers like to walk to work.With the exception of 2009 and 2012-13, new workers chose to walk about as much as to ride transit.

- Slow but steady: Bike ridership gained consistently.Unlike the volatility of the driving, transit and walking numbers, biking steadily gained new riders.

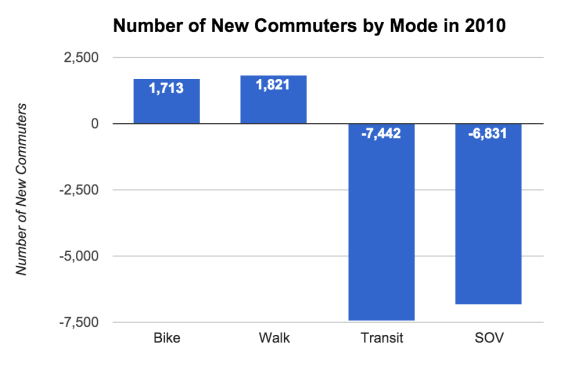

- The loss of jobs meant a lot less commuting.The lowest point of the recession was in 2010, when both transit and driving each lost more than 6,000 commuters.

- To stay employed during a recession, walk or bike to work.During the worst year of the recession - 2010 - both transit and driving lost more than 6,000 people each, but biking and walking actually saw increases.

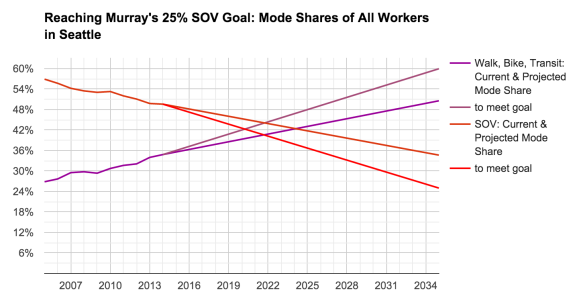

- If we maintain the growth rates of the last five years, walking, biking and transit will surpass driving single occupancy vehicles at the end of 2024.

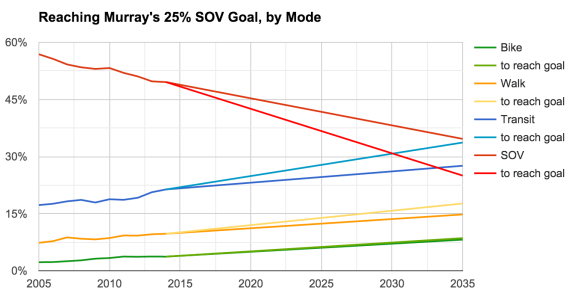

- To reach Mayor Murray's 25 percent SOV goal, Seattle must accelerate the trends.Mayor Ed Murray set a goal of reducing the commute mode share of single-occupancy vehicle (SOV) driving to 25 percent by 2035. However, based on the current rates, Seattle will have a 35 percent SOV commute mode share in 2035. To reach the mayor's goal, walking, biking and transit gains must accelerate, and surpass SOV driving in 2020.

- Seattle will achieve a 8.2 percent bike mode share in 2035, assuming current rate and that the ratio of biking, walking and transit will remain the same. By comparison, Portland had a 7.2 percent bike commute share in 2014. If Seattle's meets Murray's goal, bike commute mode share will reach 8.5 percent. Either way, based on the trends of the last five years, Seattle would fall short of its Bicycle Master Plan's goal of quadrupling bike ridership by 2030.

- To see continued gains, we must continue to invest in infrastructure. From 2007-14, Seattle built more than 53 miles of bike lanes, rechannelized several streets for safety, opened new light rail and streetcar lines, and added tens of thousands of new apartment units in walkable neighborhoods. Without these public and private investments, we would not likely have seen the substantial gains in biking, walking and transit ridership.

- With new infrastructure investments, transit, walking and biking could grow exponentially, outstripping last decade's rates.

All my projections were made assuming linear growth. However, Seattle is making huge investments in our transportation system that will pay off. New light rail, new streetcar, more bus service hours, and new downtown protected bike lanes are all scheduled to happen this year. The Let's Move Seattle levy will do more for walking, biking and transit in the next nine years than in the city's history.

Based on the recent surge of transit ridership thanks to the Central Link light rail, we can bet our transportation investments will lead to unprecedented changes to workers' commuting - for the better. If we can build out more than half the Seattle Bicycle Master Plan in the next ten years, we may yet still meet the BMP's goal of quadrupling bike ridership.

Conclusion

Based on the ACS data, new workers are significantly less likely to drive a car to work than the general population of the workforce.

But we have much more to do. The Seattle Climate Action Plan calls for reducing vehicle miles traveled by 20 percent and the Bicycle Master Plan calls for quadrupling bike ridership by 2030.

If we're to achieve either goal while maintaining adequate mobility for 120,000 new residents over the next 20 years, Seattle will have to significantly increase its pace of developing its transit, pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure. Luckily, the Let's Move Seattle Levy and Sound Transit's light rail expansion should help us make it happen.