Beats: amplitude modulation in radios and musical instruments

What do tuning a guitar and tuning a radio have in common? Both are examples of beats or amplitude modulation.

ExamplesIn an earlier post I wrote about how beats come up in vibrating systems, such as a mass and spring combination or an electric circuit. Here I look at examples from music and radio.

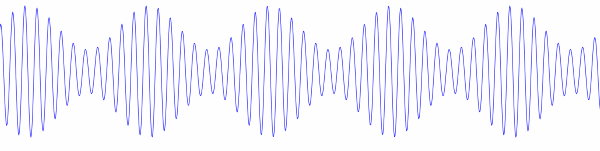

MusicWhen two musical instruments play nearly the same note, they produce beats. The number of beats per second is the difference in the two frequencies. So if two flutes are playing an A, one playing at 440 Hz and one at 442 Hz, you'll hear a pitch at 441 Hz that beats two times a second. Here's a wave file of two pure sine waves at 440 Hz and 442 Hz.

As the players come closer to being in tune, the beats slow down. Sometimes you don't have two instruments but two strings on the same instrument. Guitarists listen for beats to tell when two strings are playing the same note with the same pitch.

AM radioThe same principle applies to AM radio. A message is transmitted by multiplying a carrier signal by the content you want to broadcast. The beats are the content. As we'll see below, in some ways the musical example and the AM radio example are opposites. With tuning, we start with two sources and create beats. With AM radio, we start by creating beats, then see that we've created two sources, the sidebands of the signal.

Mathematical explanationBoth examples above relate to the following trig identity:

cos(a-b) + cos(a+b) = 2 cos a cos b

And because we're looking at time-varying signals, slip in a factor of 2It:

cos(2I(a-b)t) + cos(2I(a+b)t) = 2 cos 2Iat cos 2Ibt

MusicIn the case of two pure tones, slightly out of tune, let a = 441 and b = 1. Playing an A 440 and an A 442 at the same time results in an A 441, twice as loud, with the amplitude going up and down like cos 2It, i.e. oscillating two times a second. (Why two times and not just once? One beat for the maximum and and one for the minimum of cos 2It.)

It may be hard to hear beats because of complications we've glossed over. Musical instruments are never perfectly in phase, but more importantly they're not pure tones. An oboe, for example, has strong components above the fundamental frequency. I used a flute in this example because although its tone is not simply a sine wave, it's closer to a sine wave than other instruments, especially when playing higher notes. Also, guitarists often compare the harmonics of two strings. These are purer tones and so it's easier to hear beats between them.

RadioFor the case of AM radio, read the equation above from right to left. Let a be the frequency of the carrier wave. For example if you're broadcasting on AM station 700, this means 700 kHz, so a = 700,000. If this station were broadcasting a pure tone at 440 Hz, b would be 440. This would produce sidebands at 700,440 Hz and 699,560 Hz.

In practice, however, the carrier is not multiplied by a signal like cos 2Ibt but by 1 + m cos 2Ibt where |m| < 1 to avoid over-modulation. Without this extra factor of 1 the signal would be 100% modulated; the envelope of the signal would pinch all the way down to zero. By including the factor of 1 and using a modulation index m less than 1, the signal looks more like the image above, with the envelope not pinching all the way down. (Over-modulation occurs when m > 1. Instead of the envelope pinching to zero, the upper and lower parts of the envelop cross.)

Related posts: