Seattle’s safer speeds plan heads to Transpo Committee + Housing is more important than parking

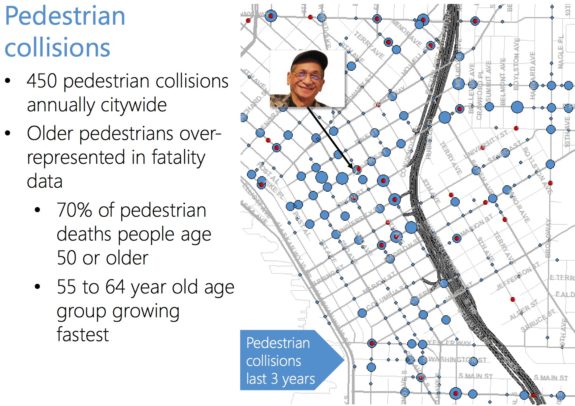

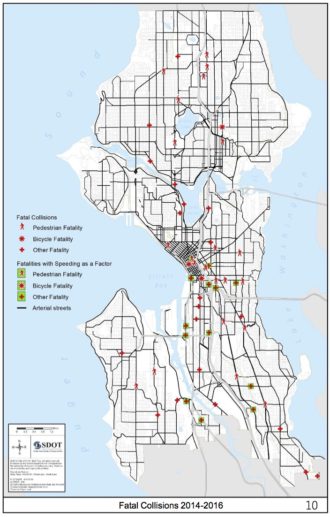

Slide from the presentation to the Transportation Committee.

Seattle's plan to lower default speed limits across the city heads to the City Council's Sustainability and Transportation Committee today. The plan - which has support from the Mayor's Office, SDOT and the City Council - needs to make it through the committee and the full City Council before getting the Mayor's approval and going into action. If all goes smoothly, that could be as soon as November.

Seattle's plan to lower default speed limits across the city heads to the City Council's Sustainability and Transportation Committee today. The plan - which has support from the Mayor's Office, SDOT and the City Council - needs to make it through the committee and the full City Council before getting the Mayor's approval and going into action. If all goes smoothly, that could be as soon as November.

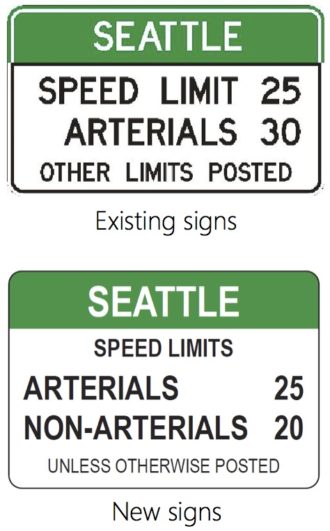

That change itself is pretty simple, but the implications for safety could be huge as we reported when it was announced. All it really does is change a bunch of signs near the city limits to spell out the new default speeds. For "non-arterial" mostly residential streets, the default limit would be lowered from 25 to 20 mph. For busier "arterial" streets, the speed would drop from 30 mph to 25 mph unless marked otherwise, as is often the case.

But when speed limits are lower on a street (and people know about the limit), the majority of people who want to follow the law will limit their top speed to that new limit. And that alone could improve safety, according to a city legislation document (PDF):

More than 10,000 collisions occur on Seattle streets annually. Less than 10 percent of these crashes involve pedestrians, bicyclists or motorcycles yet these modes make up more than 50 percent of fatalities. Vehicular speed is often the critical factor for survival in collisions. The higher a driver's speed, the greater risk to vulnerable road users.

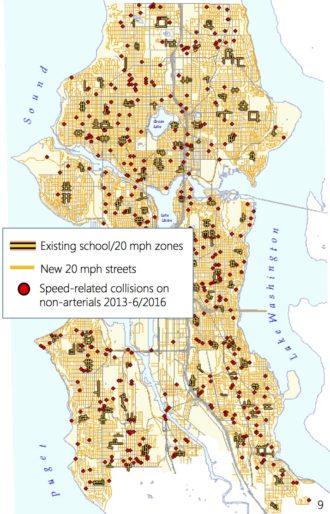

Most of the big streets obviously designed for faster speeds (Aurora, for example) have their own marked speed limits and will not be affected by this change. Those streets will need targeted road safety projects before speeds can reasonably be expected to drop. Move Seattle provides funding for about one "road safety corridor" project every year.

Such a change will have hardly any effect on how long it takes for someone to get from Point A to Point B, but it could have a big effect on the top speed their speedometer reaches during that trip (before slowing again for traffic or another red light).

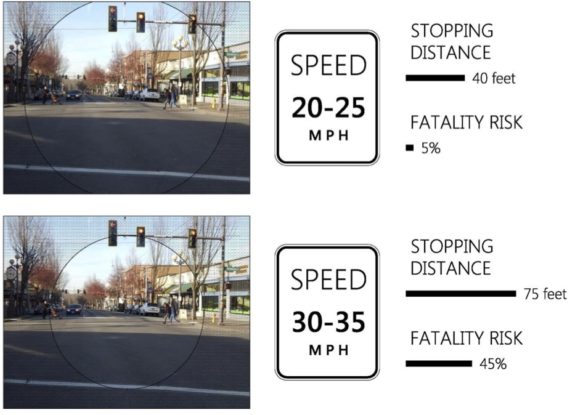

Image from the justification document.

With even modest drops in the top speed, fatal or serious injuries turn into bumps and scrapes, bumps and scrapes turn into near misses (and maybe a honk), and near misses don't happen at all. Little is gained by going 30-35 instead of 25-30, but a lot could be lost.

This change not only protects public health, but it makes the walking and biking experience more inviting, encouraging more walking and biking trips that may otherwise have been driving trips.

And in case you think Seattle is being radical with this change, note that Seattle is currently the only city in King County with a default speed limit higher than 25. The city set the 30 mph limit in 1948 during an era when many dangerous traffic decisions were made (bridges without space for walking, freeway-style infrastructure in neighborhoods, etc). It's time for a change.

Stay tuned for updates from the committee meeting starting at 2 p.m.

Stay tuned for updates from the committee meeting starting at 2 p.m.

UPDATES:

When looking at maps covered in collision, injury and death data, SDOT Director Scott Kubly wanted to remind everyone that "there are real people behind each one of these dots." This is such an important point to make, and it gets glossed over so easily when confronted with an overwhelming dataset like those posted here.

Most of the arterial streets that do not have posted speed limits at the moment are in the center city, so that's why the city is focusing their outreach on that area. Arterial streets outside the center city mostly have their own posted limits and will not be immediately impacted by this rule change.

The city does not want to go out and just arbitrarily lower those speed limits, preferring to go corridor-by-corridor and couple speed limit changes with appropriate design changes.

"We want to design a road where you're naturally going the speed limit," said Kubly. If you have a really wide street with few impediments to driving fast, lowering the speed limit will do little to change behavior. Traffic calming and modern safe streets designs are vital to reaching our safety goals. Changing the limit isn't going to get there on its own.

We will also continue to follow our standard enforcement protocols, developed with community help. People will get warning for a few weeks after the change goes into effect.

The city will still need to study speeds on a street to determine whether 85th percentile speeds are close enough to 25 mph to lower the speed limit. It was not entirely clear during the meeting if such a study is currently required by state law or not. Councilmember Rob Johnson found this limit frustrating.

"The only thing that's frustrating me about this legislation is the lack of implementation outside of downtown quickly," said Councilmember Johnson.

The legislation passed unanimously and heads to the Full Council meeting either next week or the week after.

Housing > ParkingAnother topic on the docket for the 2 p.m. meeting: A very boring-sounding Parking Benefits District that could actually be one piece of a big housing affordability mindshift. The need (or perceived need) for protecting private access to public car parking spaces is a huge impediment to building more homes in our neighborhoods. But we need to reframe the role of public car parking spaces so it is not in opposition to new homes.

Sightline explains how a Parking Benefit District could help the other HALA policies and why the city should at lease try the idea:

The reason HALA ranked the Parking Benefit District pilot so highly is that parking rules bloat housing prices, and PBDs are the most promising political strategy for changing parking rules. I've spelled out this argument in other articles (the crux is here), but I'll summarize.

Eliminating existing requirements currently on the books in almost every city, namely that housing builders install lots of off-street parking spaces, is a key strategy for housing affordability. Most people wouldn't guess it, but parking requirements (or "quotas") raise the rent-and not just by a little, but by a lot. Here's a full rundown of how they do so, but some major ways include:

- Parking quotas raise the cost of building housing, especially inexpensive housing, and they suppress the number of apartments and houses that can fit on a lot-often by a quarter to a half.

- Parking quotas block adaptive reuse of old buildings, such as vacant warehouses, to housing.

- Parking quotas disperse housing by suppressing housing units per city block, which exacerbates sprawl and therefore distances traveled, which makes transit less practical and driving more common. And driving is expensive.

At Seattle apartment and condo buildings, the cost of parking is as much as 35 percent of monthly rent, even for residents who do not use a parking space. And this estimate does not include the way parking mandates suppress the number of apartments citywide, which leads to more price competition for each of them.

UPDATE:

This issue turned into a rather interesting debate about parking revenue during the meeting. SDOT staff have been very effective at implementing an exceedingly data-driven parking management system since 2010. In some ways, maybe we shouldn't disrupt this success by introducing other factors.

But the biggest piece SDOT staff have on their side about the revenue destination (the general budget vs a parking benefit district) is that keeping the funds in a district could be at big risk of being distributed inequitably. Right now, investments can be distributed through the departments regular process, which includes an equity analysis. If the money stays in a district, it sort of goes around that analysis.

Councilmember Kshama Sawant also made the claim that parking meters are a regressive way to raise revenue. In one way, that's true: Everyone pays the same cost for an hour regardless of their income. But car ownership is very much correlated with income, so usage fees for car use are really at least somewhat progressive.

One interesting hint came up during the meeting: The parking crew is looking at the city's Residential Parking Zone program. I'm dreaming of income-based fees for an RPZ pass"