Missing Link mega study exhausts the debate + Why the Labor Council still opposes the trail

The compromise route.

Councilmember Mike O'Brien, a longtime trail supporter, and Warren Aakervik, the owner of Ballard Oil and a trail appellant, shook hands during a February press conference.

The smile on Councilmember Mike O'Brien's face somehow grew even bigger than usual while listening to longtime trail opponents and advocacy staff at Cascade Bicycle Club praise each other for finally hammering out a Ballard Missing Link compromise after decades of arguments, expensive court battles and painful bike crash hospital visits.

"I'm kinda all smiles," said O'Brien during the February press conference. O'Brien is a longtime trail supporter and the councilmember representing the district containing the missing 1.4 miles of trail near Ballard's Salmon Bay waterfront.

"When designed properly, [the city] will create a safe facility next to a major truck street," said Warren Aakervik, the owner of Ballard Oil and one of the longtime trail opponents who sued to delay the project to this point. "Hopefully we can move forward and make something safe."

In addition to announcing a compromise route that includes parts of the South Shilshole Ave route trail advocates preferred and parts of the industry-preferred Market/Leary Way route, Mayor Ed Murray also announced the creation of a design advisory group much like the group that guided the Westlake Bikeway. This group includes business owners, bicycle advocates and neighborhood representatives who are sitting down together to go detail-by-detail to hash out details to make sure the trail design works as best as it can for everyone.

"Today's major announcement ends 20 years of lawsuits, studies and counter studies," Murray said.

So it was somewhat bewildering (though sadly expected) to read a Seattle Times editorial recently saying, "The city has stuck for too long with a route loved by Seattle's biking lobby but potentially disastrous for its historic maritime sector. It is well past time to compromise and finally build the missing link on the alternative path."

It's pretty embarrassing that the Times didn't even look at the city's preferred route long enough to notice that it is practically the definition of "compromise." About a third of the route follows Market Street, skipping the tight section between Shilshole and the Locks where the trail planners and businesses would have the hardest time working out solutions. That section would not have been impossible to solve, but Market is likely much easier to build. Moving the trail over to Market will make it slightly longer and includes a small extra hill to climb, but these changes are workable. And it is the key change that finally got parties together at the table.

This is what compromise looks like.

Summary of feedback on the Draft Environmental Impact Statement.

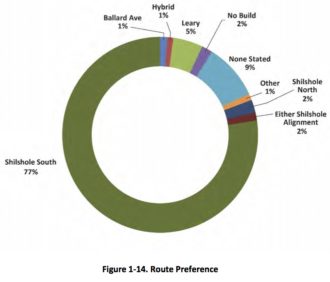

The Leary/Market route only managed to get support from five percent of people who commented on the Draft Environmental Impact Statement despite the Times Editorial Board and trail opponents pushing it for years and convincing the city to include it in the mega study. Only Ballard Ave and No Build were less popular. 81 percent of respondents preferred one of the Shilshole options, nearly all of which were in favor of the Shilshole South option specifically.

The city took the Leary/Market option off the table after the study found that it failed to adequately address the project's primary goals. Specifically, it would not fix known hazards on NW 45th Street and Shilshole Ave, which would remain the fastest, most direct and, therefore, popular route. It would be much slower, hillier and still cross as many or more driveways as the Shilshole route. The study also found that it was not consistent with the city's Comprehensive Plan or even with the brand new Freight Master Plan. If anything it would be worse for freight mobility, the extensive study found.

In other words, people's gut feelings that the Leary/Market option would be a poor Missing Link solution were supported by the extensive study. At least east of 24th Ave NW, Shilshole is the only real option for building the trail.

Why the MLK County Labor Council still opposes the trailBut gut feelings are also powering the continued resistance to any trail on Shilshole. Though some key major business owners are now on board with the compromise and the extensive environmental study found no reason why the Shilshole alignment would have anything more than minimal impacts to industry, some businesses are still holding out. And the MLK County Labor Council is standing with them.

Perhaps that's the bigger point, and why the three-and-a-half-year, $2 million environmental study has been a silly exercise all along. The decades-long fight over the Ballard Missing Link of the Burke-Gilman Trail has never been about facts, safety analyses and environmental impacts. It's about a gut feeling that a walking and biking trail and heavy industrial uses simply cannot exist side-by-side.

"I just don't believe in peaceful coexistance in this case," said MLK County Labor Council Executive Secretary Nicole Grant. "I'm looking at it with my own eyes, and I'm saying, 'This is going to be a disaster.'"

Grant doesn't mince words when she is advocating for the Council's position on issues, and our conversation was once of the best I've had about the Missing Link in the years I've been covering it. In the end, our talk became about how people who want to support each other have to come to grips with the fact that they just are not going to agree about the Missing Link. Most trail supporters - I hope - also want to support union jobs and a working Salmon Bay waterfront, and many union workers also bike and love the Burke-Gilman Trail. CSR Marine, a trail opponent, even hosts the annual Fremont Solstice Parade bike ride body painting party.

"Even if people never really agree, it's still helpful for cyclists to know where people are coming from," she said, "that it's maybe more complex than it typically gets painted."

Grant said she has worked on building parts of the Burke-Gilman, and the Missing Link construction will certainly provide a lot of good union work.

"I'm a serious supporter of the Burke-Gilman Trail," she said. "I don't want to be construed as a trail hater, because I'm not."

But Grant and the Council oppose the compromise route the city, trail advocates and some major industrial players have agreed to develop. They are standing firm against any option on Shilshole.

"Our argument is super basic: Shilshole is taken," she said. The street must be reserved "for things that are not recreation and not arterial transportation methods for any kind of transit: Car, bike or bus."

With Ballard growing in population so quickly in recent years, people who work in industrial Salmon Bay only grow more worried about the very existence of their workplaces. Literally and psychologically, the trail brings residential Ballard that much closer to industrial Ballard. And even though advocacy for a completed trail started long before the recent development boom in Ballard, the same economic forces making it impossible for working people to afford homes in Seattle are putting pressure on industrial lands. The trail plays into worries that industrial businesses will be replaced by high-end condos and offices once the Salmon Bay waterfront land gets valuable enough.

"I like that Seattle's becoming a big city," said Grant. "It's cool that Ballard is such a lively community " but people want there to be these fisheries, and these heavy industrial and maritime uses down there."

Friction between these uses can get tough "on the edges where they meet," she said. And the Missing Link is trying to cut into the industrial side of that edge.

"The only way [the trail] will ever really be safe down there is if it stops being a hardcore industrial area," said Grant. "There are some places that are really dangerous, and it's hard to say what the solution is. But if the choice is, make a couple blocks of the city safe for every user at the expense of the major fishery in North America " That is a billion dollar industry that supports tons and tons of people and their livelihoods."

The trail's mega study states that the businesses and the jobs there would not be harmed by the trail:

[N]one of the Build Alternatives are expected to displace existing uses or cause changes that would result in the loss of a business. Impacts are not expected to affect business operating costs to the extent that they would be unable to operate.

But despite the enormous amount of study that went into the Environmental Impact Statement, Grant simply doesn't buy this conclusion.

"The workers and the businesses know what will work for them," she said.

I challenged Grant on her point about allowing Shilshole to remain dangerous, asking her if labor would be OK with a plant where one of the lines kept injuring workers.

"No, we wouldn't," she said.

In many ways, Vision Zero and the modern safe streets movement is modeled on very successful workplace safety efforts that labor unions led and continue to lead. Vision Zero just takes those concepts and applies them to public streets. That is part of what makes this Missing Link fight so tough. Safe streets advocates and labor should be on the same side.

"We support safe streets," said Grant. "I don't think we are natural enemies by a long shot." The Labor Council stood with safe streets advocates during the campaign to pass the Move Seattle Levy in 2015, for example.

But fears that the trail on Shilshole will kill jobs - supported by the mega study or not - still take precedent for the Labor Council.

"All the workers are really busting ass down there trying to make the industries successful," she said. "It's a big burden to say, 'Coexist with this trail because we've welcomed these families and we've welcomed these people to recreate here. So you better not hit them, and you better get the cement to the site before it dries out.'"

In the end, the city just has to make a choice. The only thing nearly everyone agrees about is that the trial needs to be completed somewhere. Only 2 percent of people who commented on the Draft EIS preferred "No Build."

"I don't envy the city in this process," said Grant. Because they need to make a decision, and there is no option that appeases everyone.

So Mayor Murray and SDOT have done just that. They are going with a compromise route that at least got some major business owners on board. And they created a design advisory group to hash out the details step-by-step.

"The DAC is tasked with looking at the preferred alternative block by block, to ensure that the final design of the trail prioritizes the safety of all who use the corridor, and preserves access to water-dependent businesses and adjacent buildings," wrote Cascade's Kelsey Mesher in a recent blog post. We must hold the city to their word that they will get the details right so the trail and industry can live side-by-side. Because no matter how many hours of your life you have spent arguing about the Missing Link or healing from wounds you got from crashing there, you should still support the jobs along Salmon Bay.

Barring any wild new developments, union workers are going to finally break ground on this thing in 2018. It should be difficult to successfully sue now that there is an FEIS, though we've all heard that one before. Aside from the fine details the design group is tasked with working out, there's just nothing left for the city to study or debate. We need to finish it and move onto other issues facing our city.

Hopefully the next big thing is an issue where safe streets advocates and labor can work together instead of being at odds.