A Break in the Nuclear Waste Impasse?

Spent nuclear fuel has continued to accumulate at sites across the nation, paralyzed by a government deadlock on a nuclear waste management strategy formally established 35 years ago. Can recent developments offer a breakthrough?

February marked 20 years since the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) defaulted on a "standard contract" with the nation's reactor operators to begin disposing of highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel (SNF) as required by the Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA) of 1982. Despite a series of recent developments that could revive the Yucca Mountain deep geologic repository in Nevada, making it the final destination for the nation's spent fuel, as required by amendments to NWPA in 1987, a long-standing political deadlock has left the U.S. with one option that has nearly every stakeholder attached to the nuclear power industry despondent-to wait.

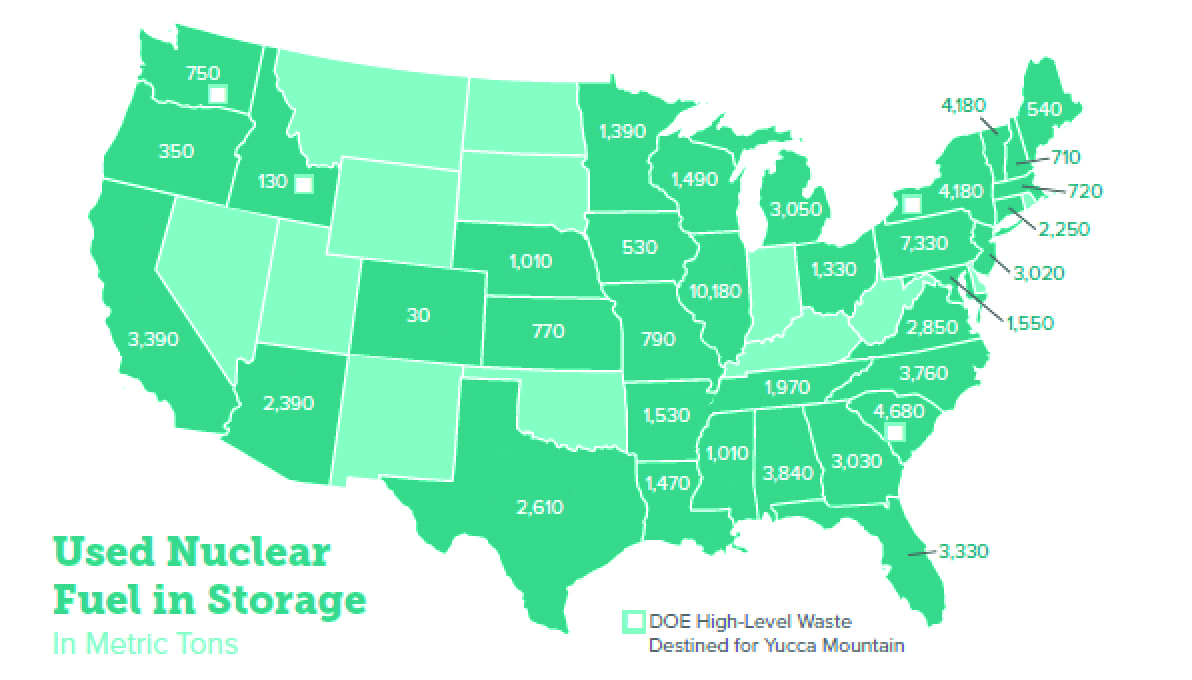

But waiting is a treacherous game. About 80,150 metric tons heavy metal (MTHM) of SNF-fuel withdrawn from a nuclear reactor following irradiation, which is referred to as "used" fuel by the nuclear industry because it contains potentially reusable uranium and plutonium-is in temporary storage at 75 reactor sites scatted across 33 states, according to the DOE's Sandia National Laboratories. Nearly a third of that SNF-25,400 MTHM-is in dry storage in about 2,080 cask or canister systems, and the balance is in spent fuel pools, mainly at reactors, or otherwise stranded at independent spent fuel storage installations (ISFSIs) if the reactor has been shut down.

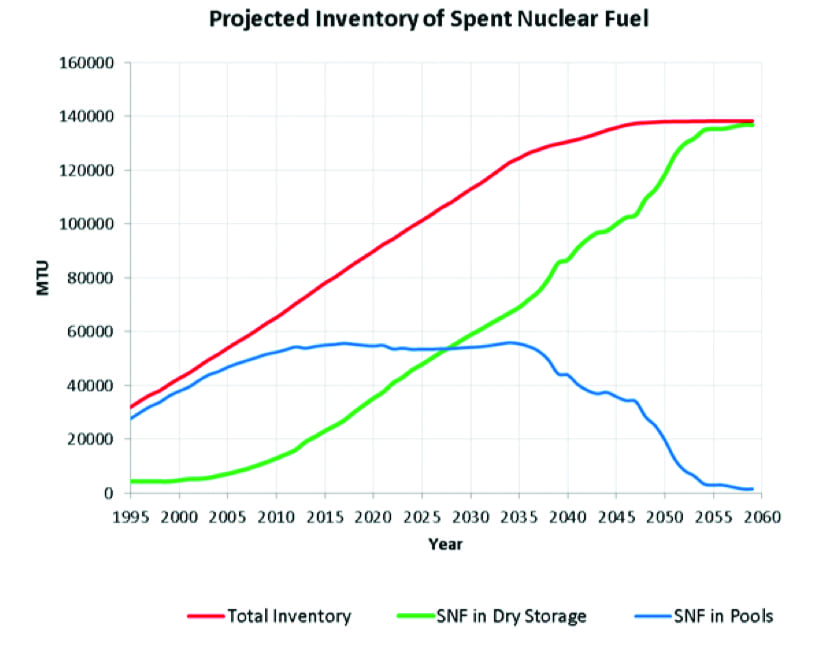

Another 2,200 MTHM of SNF is generated nationwide each year. Because U.S. pools have reached capacity limits, about 160 new dry storage canisters are loaded each year. Sandia presents the problem starkly: If the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) grants all license renewals requested by the bulk of the nation's 99-reactor fleet, and assuming no new reactors will be built and no action is taken on long-term disposal, the nation's projected SNF inventory will surge unrelentingly upward (Figure 1)-and with it, risks for health, security, and the environment.

As crucially, the taxpayers' burden for the federal government's inaction on the nuclear waste impasse is getting ever heavier. Getting the project started hasn't been cheap: From fiscal year 1983 to the DOE's license submittal for Yucca Mountain to the NRC in 2008, the DOE spent nearly $15 billion (in 2010 dollars) to investigate developing a repository. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) says that from fiscal year 2009 to fiscal year 2016, the agency received an additional $1.4 billion in appropriations for nuclear waste management. Meanwhile, the Nuclear Waste Fund-a U.S. Treasury account collected via a fee charged to ratepayers over 30 years-today holds a balance of about $37 billion. Mostly unused, owing to paralysis of the Yucca Mountain project, it continues to accumulate interest of about $1.7 billion a year from investments in Treasury securities.

And worse, because the DOE entered into NWPA-required contracts with every U.S. nuclear generator to dispose of SNF no later than January 1998 in return for the fee, nuclear generators have recovered costs for SNF storage and management by suing the DOE. The first settlement the Department of Justice reached under such litigation in July 2000 allowed PECO Energy (now part of Exelon) to keep up to $80 million in nuclear waste fee revenues for 10 years. However, other generators sued the DOE to block the settlement, and the Eleventh Circuit ultimately ruled in September 2002 that compensation for missing the disposal deadline would have to come from general revenues other than the Nuclear Waste Fund. Those nuclear waste payments now come out of the Treasury's Judgement Fund (see sidebar: "The Judgement Fund: The Taxpayers' Nuclear Waste Burden"), a permanent account that requires no appropriations and is used to cover damage claims against the U.S. government.

| The Judgement Fund: The Taxpayers' Nuclear Waste Burden An audit of the Department of Energy's (DOE's) Fiscal Year 2016 Nuclear Waste Fund financial statement, conducted by accounting firm KPMG for the DOE Office of Inspector General and released in December 2016, showed 38 lawsuits had been settled as a result of the DOE's partial breach of contract ensuing from inaction on Yucca Mountain, and 41 cases were resolved by final unappealable judgements. As of September 2016, the Treasury's Judgement Fund paid $4.4 billion for delay damages and $1.7 billion from final court judgments for a total of $6.1 billion. The DOE said the government's ultimate liability-if it manages to settle with all 45 utilities under contract-is likely to be about $30.8 billon. Industry estimates suggest liabilities could soar to as high as $50 billion. The Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI), a group that represents the bulk of U.S. nuclear generators, said that damage payments average $2.2 million per day-or about $800 million per year. While "a significant part" of the nuclear fleet has settled their lawsuits with the government, the settlements only cover a certain amount of time, NEI's Rod McCullum told POWER. "If the government continues to not act, at some point they'll be back in court." Meanwhile, not all settlements are final. "Some companies just want to have the settlement and to send the [annual reimbursement claims for delay-related waste storage costs incurred to the Justice Department]," he said. "Other companies think they can get a better deal out of the court, so they keep suing to get the settlement and send the bill." The bottom line is: "Either way, the taxpayers keep paying," he said. "The taxpayers cannot escape this liability." |

"Whenever the government loses a lawsuit, money just magically comes out of the Judgement Fund," Rod McCullum, senior director of the Nuclear Energy Institute's (NEI's) Used Fuel and Decommissioning arm, told POWER in February.

And the Judgement Fund is just the tip of the iceberg. There is a mounting bill that Anthony J. O'Donnell, a commissioner at the Maryland Public Service Commission who also serves as chair of the Subcommittee on Nuclear Issues-Waste Disposal at the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC), told a House Interior, Energy, and Environment subcommittee in September 2017 has "nothing to show for it." Ratepayers, who already funded the one mill (one tenth of a cent) per kilowatt-hour fee to bloat the Nuclear Waste Fund for decades until the D.C. Circuit suspended fee collection in 2013, also paid for the original waste storage at facilities scattered across the nation (Figure 2), as well as to rerack or consolidate used fuel pools, and for onsite, out-of-pool dry cask storage.

For the nuclear power industry, which is reimbursed for storing SNF onsite, the stalemate is still proving costly in terms of lost opportunity, McCullum said. "The members are tired," he said. One consideration is that a utility must divert resources, including manpower, equipment, and capital, to deal with SNF when they could be used instead to make a plant more efficient in an increasingly competitive marketplace. At the same time, "You've got a long-term situation where you can decommission a plant, but you are still maintaining a nuclear stake," he said.

Another consideration, as Rita Sipe, manager of Duke Energy's Nuclear Fleet Communications, in February told POWER, is that used fuel pools and dry cask storage sites, which Duke has located at five of the company's six operating nuclear plants, require operations and maintenance. "We don't split fuel storage functions out separately-they are part of plant systems, components, and structures, and are maintained by skilled and experienced employees in the same way other plant equipment is maintained," she said. However, "on-site storage is not a permanent solution," she added, noting that the company has urged the government to resume work at Yucca Mountain to fulfill its statutory responsibilities.

The Political StandoffConsensus is that the unsurmountable effort to implement any solid policy relating to long-term management of nuclear waste in the U.S. is centered around Yucca Mountain (Figure 3). The problem comes mainly from the State of Nevada's fierce opposition to the planned repository on the grounds that it is unsafe and vulnerable to potential volcanic activity, earthquakes, water infiltration, underground flooding, and nuclear chain reactions.

The state's contentions were at the heart of the Obama administration's abrupt policy decision to scrap the project. In a move designed to cement the repository's fate and entomb any previous efforts to build it, the Obama administration in March 2010 took the step of withdrawing the Bush administration's 2008-submitted NRC license application for Yucca Mountain "with prejudice," meaning the application could not be resubmitted.

But the NRC's Atomic Safety and Licensing Board (ASLB) in June 2010 denied the DOE's license withdrawal motion, ruling that the NWPA prohibits the DOE from withdrawing the application until the NRC determines whether the repository is acceptable. While NRC commissioners sustained the ASLB decision in a tie vote in September 2011, the NRC stalled further consideration of the application, citing "budgetary limitations." That prompted intervention by the D.C. Circuit, which ruled in August 2013 that the commission must continue work on the Yucca Mountain application as along as funding is available.

Intent on forging a strategy that didn't include Yucca Mountain, the Obama administration also established the Blue Ribbon Commission on America's Nuclear Future (BRC), a nine-member panel of nongovernmental experts tasked with development of alternative waste disposal strategies. At the end of the two-year deliberations period, the BRC recommended that a new "single-purpose organization" be given the authority and resources to begin developing-using a "consent-based approach"-one or more nuclear waste repositories and consolidated storage facilities.

In response to the report, the DOE in January 2013 quietly issued-without as much as a press release-an outline for a new nuclear waste program. Essentially, it foresaw a pilot interim spent fuel storage facility opened by 2021, a larger-scale storage facility (possibly an expansion of the pilot) by 2025, and a geologic disposal facility by 2048-50 years after the initial planned opening of Yucca Mountain.

But the BRC's entire effort was thrown amok almost immediately by the Trump administration. Stating a priority to restart Yucca Mountain, the administration in May 2017 submitted a congressional budget request for FY2018 with more dollars for both the DOE and NRC. However, in July the Senate Appropriations Committee's FY2018 Energy and Water Development Appropriations bill provided no funding for Yucca Mountain. It instead authorized the DOE to develop consent-based pilot interim storage facilities to handle fuel from closed reactors currently stored at ISFSIs. This February, the Trump administration again requested funds to revive licensing as part of a larger $4.4 trillion budget blueprint for FY2019, which runs from October 2018 to September 2019.

In the backdrop, the nuclear power industry is driving a campaign to draw attention to H.R. 3053, a bill introduced by House Republican John Shimkus (Ill.) in June 2017. Called the Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act of 2017, it cleared the House Energy and Commerce Committee in October 2017 and seeks to satisfy a major licensing condition by giving the DOE full control of the public land. It also expands the capacity limit on the Yucca Mountain repository from 70,000 to 110,000 metric tons, authorizes the DOE to store SNF at an NRC-licensed interim storage facility owned by a nonfederal entity, and provides mandatory funding for specific stages of repository development.

While the Trump administration's recent budget request alone may not move H.R. 3053 to the floor, both are "reassuring" developments that could resolve political and financial hurdles blockading Yucca Mountain development, said Katrina McMurrian, executive director of the Nuclear Waste Strategy Coalition (NWSC), an entity whose membership includes state utility commissions, state consumer advocates, state energy officials, and owners of operating and shutdown reactors.

'Give Them the Old Razzle-Dazzle'The courts, too, have been pivotal in shaping the repository's fate. In 2013, the D.C. Circuit ended a dispute that had been stewing since 2010, dealing a landmark victory to NARUC and industry group NEI, which sued the DOE for collecting what they charged were "legally defective" fees for nuclear waste disposal. Ruling that the fee was unlawful in 2012, the court gave the DOE six months to conduct a reevaluation of the Nuclear Waste Fund. But after the DOE responded that the fees were necessary because the administration and Congress intended to pursue a new nuclear waste strategy-and the agency itself had unveiled a phased, consent-based approach to siting and implementing a nuclear waste management and disposal system-Senior Circuit Judge Lawrence Silberman, in an often sardonic seven-page decision, said that the fee should change to zero until the Energy Secretary chose to comply with the NWPA.

"According to the Secretary, the final balance of the fund to be used to pay the costs of disposal could be somewhere between a $2 trillion deficit and a $4.9 trillion surplus," Silberman wrote. "This range is so large as to be absolutely useless as an analytical technique to be employed to determine-as the Secretary is obligated to do-the adequacy of the annual fees paid by petitioners, which would appear to be its purpose." Wryly, he added: "(This presentation reminds us of the lawyer's song in the musical, 'Chicago,' 'Give them the old razzle dazzle.')"

Agony at the DOEPerhaps no stakeholder has agonized over the nuclear waste impasse as much as the DOE. When the agency delivered (by truck) its 17-volume, 8,600-page application for Yucca Mountain to the NRC in June 2008, it projected the repository could begin receiving waste in 2020-22 years later than the 1998 goal established by the NWPA. At the time, the agency celebrated the milestone with significant fanfare because for the first time since Congress enacted the NWPA, the focus shifted away from the DOE and to the NRC.

A decade has now dissipated without any substantial progress. For career DOE employees, which had to stand by the Obama administration's actions to terminate the program, and then endure the BRC's consideration of a fresh nuclear waste management strategy beyond Yucca Mountain, a sense of futility is pervading.

Despite Trump's announced commitment to restart Yucca Mountain, and despite multiple hearings in Congress on the stream of proposed actions-including H.R. 3053-despite repeated slogs through the appropriations process, no funding has come through to resume the project. "So, where we are today is where we've been since 2000," a DOE official told POWER.

Even if Trump's FY2019 budget makes it through appropriations, the $120 million requested is only a start for the DOE. Though the DOE hasn't conducted a recent "bottom-up" estimate, agency officials noted a much larger annual figure will be needed to fully participate in the licensing proceeding. As an example, in 2010-the last year that the DOE's Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management got an appropriation to fully participate in the repository licensing-the appropriation was about $198 million.

"The licensing proceeding itself is a large complex legal proceeding," requiring a "large number of technical experts in a variety of technical disciplines, scientists, engineers, attorneys," a DOE official explained to POWER. Meanwhile, the DOE has only completed enough design work to satisfy the safety analysis, which means that even if the NRC licenses construction, design work that will result in blueprints still needs to be completed, another official said. More funds will then be needed for actual construction of the repository-including excavation, surface handling facilities, and an underground railroad-as well as related external infrastructure, including a railroad, which the DOE has deemed the preferred method of getting spent fuel from reactor sites to Yucca Mountain.

The railroad itself wouldn't need NRC authorization but it could take "years and hundreds of millions of dollars," a DOE official said. "None of this is rocket science. It's just that the repository and infrastructure related to it are so big, that it's a lot of money," the official added. "The only scientific problems you really have are political science challenges."

At the NRC, meanwhile, similar troubles bar it from taking the next crucial step to schedule an adjuratory hearing before it issues a licensing decision. Even though the entity is eligible to use the $40 billion Nuclear Waste Fund, any money it gets must be approved by Congress. In February, the NRC requested $48 million for its review of the Yucca Mountain application for FY2019. The NRC last received $10 million from the fund for work related to the closure of Yucca Mountain licensing support activities in FY2011, which was only 34% of what it received in FY2010 ($29 million) and 20% of what it received in FY2009 ($49 million).

Alternatives to Yucca MountainAssuming Yucca Mountain development is stonewalled for now, and with identification of a new geological repository suspended in 2017, only two other options are legally afforded by the NWPA. One possibility is to construct one or more interim storage facilities to consolidate SNF in willing host communities to which the DOE could move SNF until a long-term geological SNF storage facility opens. The other is to utilize federal monitored retrievable storage (MRS) facilities, in which the DOE could store nuclear waste from commercial nuclear plants pending permanent disposal or reprocessing.

Despite the DOE's attempts in the late 1980s to persuade states to host an MRS facility, no MRS facilities have been proposed. Meanwhile, two private companies have expressed interest in developing private consolidated interim waste storage sites.

In April 2016, waste management company Waste Control Specialists (WCS) filed an application for a NRC license to build an interim SNF storage facility as early as 2022 at a 14,000-acre site near Andrews, Texas, where the company currently operates two low-level radioactive waste storage facilities with local support. However, the company asked the NRC to suspend consideration of the application a year later, citing estimated licensing costs that were "significantly higher than we originally estimated." WCS didn't immediately respond to POWER's questions about the status of its application.

SNF storage system maker Holtec International, which filed an NRC application (Figure 4) in March 2017 for a facility to be located on land provided by a local government consortium near the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico, also declined to comment on the projects' costs and timeline or the status of the application.

While the industry is enthusiastic about the prospect of a centralized interim storage facility, it has urged the DOE to keep working on completion of Yucca Mountain. As an NEI spokesperson told POWER, "[Centralized interim storage] is a viable but not substitute option for a repository." Meanwhile, while the DOE recognizes the NWPA's authorization of interim storage, the law requires that progress of an MRS must be linked to progress of Yucca Mountain, an agency official pointed out. "So, under current law, there's one solution, and its Yucca Mountain," the official said.

From a technical perspective, beyond deep geologic disposal, the only plausible alternatives for permanent nuclear waste management are permanent surface storage or reprocessing, Peter Swift, senior scientist at Sandia National Laboratories, told POWER. "Permanent surface storage could work in principle, but it's not a realistic option. Meeting the same regulatory requirements for isolation that are applied to deep geologic repositories would entail an open-ended commitment to maintain secure surface facilities for one million years and could require repackaging SNF perhaps as frequently as every 100 years," he said.

Meanwhile, reprocessing SNF to generate new reactor fuel is a proven technology, but it has never been shown to be economically attractive in the U.S, Swift noted.

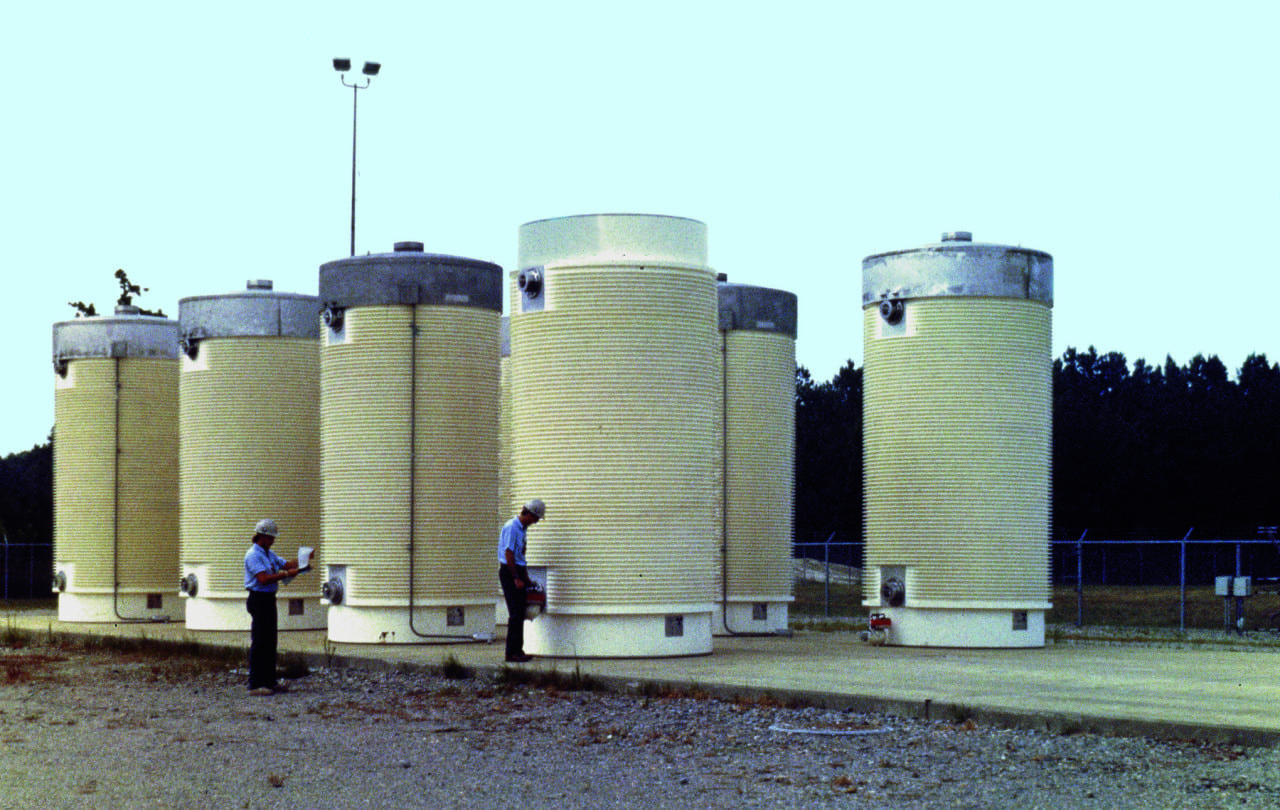

If Yucca Mountain doesn't come to fruition and another geologic repository isn't developed, storing SNF in dry storage systems as they are currently (Figure 5) may be the nation's only recourse-other than hoping that hard reality will serve to break the impasse on nuclear waste. a-

-Sonal Patelis a POWER associate editor.

The post A Break in the Nuclear Waste Impasse? appeared first on POWER Magazine.