Bike lanes are for cars

The opening of the 2nd Ave bike lane.

People do not need bike lanes to ride a bike. People driving cars need bikes lanes to protect them from intimidating or harming people on bikes.

The laws in Washington State are clear. Bikes are vehicles, so people are legally allowed to bike on any street or highway that is not a limited access freeway (I-5, I-90, SR 520, the Viaduct, the Battery Street Tunnel, the upper West Seattle Bridge). You can go out and bike down the busiest street in your neighborhood or downtown or wherever you want at whatever speed you feel comfortable going, and the law says you are doing the right thing.

Let's wave a magic wand and change people's driving habits so they fully respect the rules of the road and always pay perfect attention. In this world, even an eight-year-old kid can bike to school going eight miles per hour down 4th Ave or Rainier Ave or 1st Ave S or 35th Ave NE, and every person driving would slow down and patiently wait for opportunities to pass her safely. She wouldn't be afraid to bike because everyone follows the rules so perfectly. And she wouldn't need bike lanes. This is a wonderful "vehicular cycling" utopia. Unfortunately, it is fantasy.

In real life, you'll likely be in for a stressful ride on these busy city streets. People might blare their horns at you. Some may even make a close pass to "teach you a lesson." Others may pass closely or narrowly avoid hitting you because they are simply not paying attention or for whatever reason don't feel they need to slow down and wait for an opportunity to pass safely. All these intimidating or dangerous actions are illegal, but the odds the person behaving this way will get a ticket are extremely low. Just because you have a right to bike there doesn't mean people in bigger, more deadly vehicles will respect that right. For some reason, even otherwise friendly and loving people are capable of treating fellow human beings with such ugliness once they are behind the wheel of a car.

As you might expect, biking in these conditions does not appeal to very many people. In places where biking to get around requires you to bike on such streets, biking rates are very low.

This is where bike lanes come in. From one perspective, a bike lane designates space on a road for people to bike. From another perspective, a bike lane is just enforcing the rights of people biking to safely get wherever they are going without fear that someone driving a car will infringe on those rights. From yet another perspective, bike lanes are necessary mitigation for a destructive and dominating car culture that has overrun our public streets thanks to a century of unbalanced investments to prioritize car supremacy.

If there were no cars, we wouldn't need bike lanes. Therefore, bike lanes are for cars.

Click here for the interactive version.

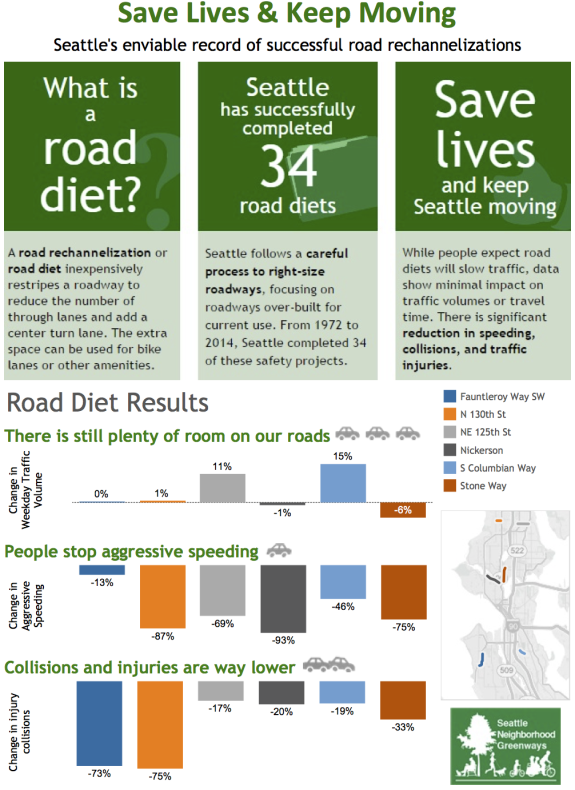

But bike lanes are also for cars in an even more direct way. Collision data shows that streets that have bike lanes have fewer and less serious car crashes. People in cars are the primary beneficiaries of safety improvements when bike lanes are added to a street. A person's odds of living a full healthy life improve every time the city builds another bike lane, even if that person never rides a bike. Because any change to a street's design affects all the users of that street.

When there is too much space on a street for cars (too many lanes or lanes that are too wide, for example), chaos fills the voids. Making a left turn across two lanes is vastly more dangerous and unpredictable than turning across one lane, for example. And the faster people are driving, the more likely someone will be killed or seriously injured when the unsteady balance of traffic fails and kinetically-charged steel collides with flesh. Car collisions are a leading cause of death in the U.S., especially for children and young people.

But a bike lane is not enough. Just because a stripe of paint has designated a space of the street for biking does not stop some people in cars from parking there or driving in that space to pass other cars. Again, these behaviors are illegal, but the odds of a ticket are very low. Barriers are needed to protect those bike lanes from infringement and keep people driving in the appropriate lane. So, just as bike lanes are for cars, so are the curbs, planter boxes and plastic posts needed to keep bike lanes car-free.

But a protected bike lane is not enough, either. Because when someone biking in a bike lane and someone in a car turning across that bike lane reach an intersection at the same time, the person driving is supposed to yield. But as we know, people driving often do not. So we need traffic signals or other significant intersection changes to prevent people from illegally turning across a bike lane. Those traffic signals with pictures of little bikes on them? Yeah, those are also for cars.

I say all this because there's this strange conversation going on in the press and at City Hall about the cost of downtown bike lanes. Mike Lindblom at the Seattle Times wrote a very good story about how the 2nd and 7th Ave bike lane projects ballooned in cost to something like $12 million a mile, a huge sum that SDOT leadership is citing as a reason the bike lane promises made to Move Seattle voters are in jeopardy.

But Lindblom's reporting shows that a big percentage of the project costs have little to do with bike mobility or safety. The 2nd Ave project, for example, added new traffic signals to three Belltown intersections at great cost. These signals are for everyone, not just people biking. That's why SDOT called the project the "2nd Ave Mobility Improvements Project," not the "2nd Ave Bike Lane Project."

But this is just an extreme example of investments made in the name of biking that really help every road user. It's pretty absurd to have different pools of money for specific modes of transportation, since most investments in city streets are inherently multimodal. But that is how the Move Seattle levy was written. So we have to ask to what extent the pool of money for bike lanes should be charged for new street lights, new traffic signals that mostly help people driving cars or segments of bike lane that were raised to sidewalk level to help a hotel valet zone. If it is multimodal in action, shouldn't it be multimodal in funding?

Vision Zero is supposed to be a core principle for all of SDOT's work, not just a side project with a limited budget. Every SDOT investment should put eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries as the primary goal. If bike lanes are the most cost-efficient way to achieve that goal, then bike lanes shouldn't be limited only to one separate pool of funds.

The troubling conclusion of this story that bike lanes cost $12 million a mile is that it becomes a reason to build fewer bike lanes. The more stuff SDOT can bill to the bike budget, the fewer bike lanes they will need to build for the duration of the levy.

But that eight-year-old biking to school doesn't care which SDOT funding pool paid for which parts of the street. She just wants to have fun getting to school safely on a bike. Our city's leaders can either sit around and argue about internal budgeting or they can get to work creating a safer and more comfortable city for the people. It is far too early in the life of this levy to admit failure and give up.

Seattle needs to figure out how to deliver the safe and connected bike network it promised to voters. Obviously, a big part of the solution is to get costs under control. Another part of the solution is to stop putting projects into modal silos and start acting multimodal. Because bike lanes are for bike mobility and local businesses and walking safety and transit access and freight mobility and parks and schools and public health. But mostly, bike lanes are for cars.