Dozens of Cities Have Secretly Experimented With Predictive Policing Software

The use of PredPol-a predictive policing software that once advocated for a controversial, unproven "broken windows" approach to law enforcement-is far more widespread than previously reported, according to documents obtained by Motherboard using public records requests.

PredPol claims to use an algorithm to predict crime in specific 500-foot by 500-foot sections of a city, so that police can patrol or surveil specific areas more heavily.

The documents obtained by Motherboard-which include PredPol contract documents, instructional manuals and slide presentations for using the software, and PredPol contract negotiation emails with government officials-were obtained from the police departments of South Jordan, UT; Mountain View, CA; Atlanta, GA; Haverhill, GA; Palo Alto, CA; Modesto, CA; Merced, CA; Livermore, CA; Tacoma, WA; and the University of California, Berkeley using public records requests. These cities and municipalities are home to over 1 million people, according to the most recent census data available. In October, BoingBoing's Cory Doctorow published a story speculating that these cities had contracts with PredPol, based on an anonymous researcher's study of the company's URL structures and login portals. These documents confirm these cities have or had relationships with the company.

One of the documents the company gave to police that was obtained by Motherboard notes that predictive policing "benefits potential offenders" by preventing them from committing crimes: "That's one less chance for them to run afoul of the legal system, and that does benefit them," it says. Other documents shared with law enforcement list some of PredPol's former customers, including an additional 15 American and British cities; one of the documents notes the company has "many more" customers that have not been listed. The company also retains sensitive crime data indefinitely on servers owned by a third party.

Previous reports state that California cities Los Angeles, Elgin, Oakland, Richmond, and Milpitas-which collectively have a population of more than 4.72 million-all used PredPol's software at one point. The most recent available documents obtained by Motherboard show that Modesto, Merced, and the University of California Berkeley still have contracts with the company. Livermore does not plan to renew its contract with PredPol, which ends this month, according to these documents.

PredPol slide presentations included in the documents also claim that the company had "current and near term deployments" in Santa Cruz, CA; Morgan Hill, CA, Fairfield, CA, Los Gatos/Monte Sereno, CA; Campbell, CA; Salinas, CA; Alhambra, CA; Lansing, MI; Seattle, WA; San Francisco, CA; Columbia, SC, and Manhattan, KS as of 2013. As of 2014, another PredPol slide presentation claimed the company also had current and hear term deployments in Little Rock, AK; Kent, England; Reading, PA; "and many more." Motherboard has not confirmed if these contracts are still ongoing, but police departments in Columbia, San Francisco, and Los Angeles told Motherboard they have "no responsive documents" in response to public records requests filed with the agencies.

When reached for comment by Motherboard, PredPol CEO Brian MacDonald said that the number of active PredPol customers is a "confidential internal metric."

Got a tip? You can contact Caroline Haskins via email at caroline.haskins@vice.com and ask for Signal.

'How predictable is crime?'Predpol explicitly encouraged police departments to dedicate their resources towards petty crime, according to documents acquired using public records documents last year. "Problem solving... that is oriented towards reducing misdemeanor crime may also reduce felony crime," one document reads.

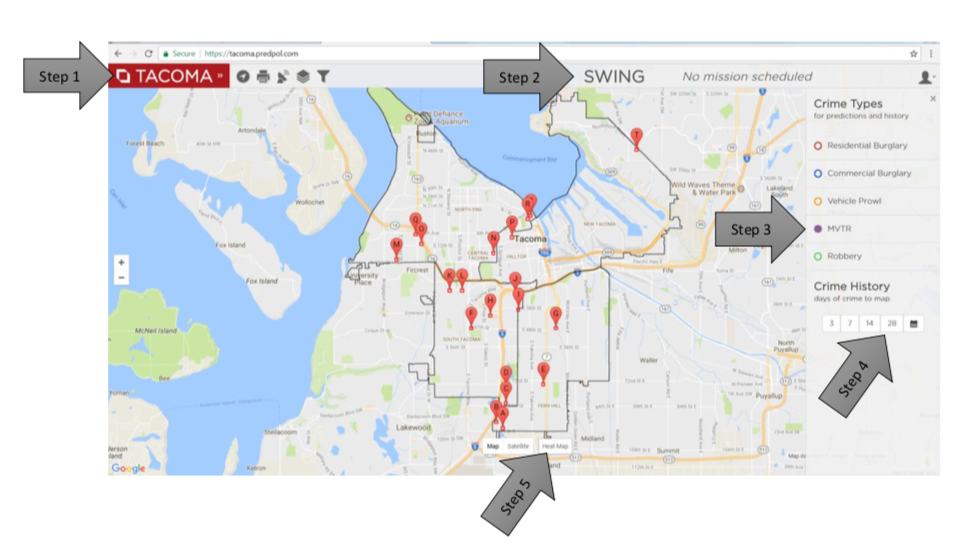

PredPol generates place-specific crime forecasts police officers on a scale as small as 500 by 500 square feet, which can pinpoint, in some cases, individual houses or groups of houses. These forecasts are generated assuming that certain crimes committed at a particular time are more likely to occur in the same place in the future. The history of crime in a particular area can be visualized on a 3, 7, 14 or 28-day scale.

"PredPol's boxes are chosen using only the what, when, and where of incidents that have already occurred in your city," a PredPol document titled "How predictable is crime," and shared with the city of Tacoma, reads. "We take anywhere from 3-10 years of crime data and run the relevant points of information through our algorithm. Long and short term trends, recurring events, and environmental factors are all taken into account."

PredPol recommends policing areas where crimes have already been reported. Criminology experts have pointed out that while this approach helps direct and organize policing, it does not ensure that better or improved policing will occur.

Shahid Buttar, the Director of Grassroots Advocacy for the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), told Motherboard that it's impossible to expect unbiased results from predictive policing technology, because the data it analyzes is structurally biased. Predictive policing is "driven by what seems to be objective historical data that itself reflects longstanding and pervasive bias," Buttar said. "If you overpolice certain communities, and only detect crime within those communities, and then try to provide a heat map of predictions, any AI will predict that crimes will occur in the places that they've happened before."

Andrew Ferguson, a professor of law at the University of the District of Columbia School of Law, told Motherboard that even though it's being implemented in police departments around the country, we don't know whether predictive policing is effective at reducing crime. "There has been a lack of objective science about efficiency and effectiveness of predictive policing," Ferguson said. "There really hasn't been much external validation of whether the technology works, what it even means, what are you comparing it to, and there's been a lack of research and science on that."

"We are talking about police, and people die at the hands of police every day in the United States."

A section of the "How predictable is crime" document sidesteps potential "privacy and constitutional concerns," and ignores the fact that over-policing certain areas is likely to disproportionately affect people of color.

"Although they might not see it this way, it benefits potential offenders. If you've prevented them from committing a crime, that's one less chance for them to run afoul of the legal system, and that does benefit them," Jeffrey Brantingham, chief of research and development at PredPol, wrote in the document. "Crime prevention benefits everybody. I can't see how that wouldn't be an appropriate direction to move."

Brantingham also argues that PredPol should be understood as a resource allocation tool. "A lot of what we do with predictive policing is just a much more refined approach to hot spot policing," Brantingham says in the document. "In some ways, you might think of it as being a step in the right direction. It actually defines, in a much more limited and precise way, where law enforcement is needed " A lot of the work we do on prediction is not about predicting who is going to commit a crime, but about where and when crime is likely to occur, regardless of whom the offenders are."

Image: A screenshot from a slide presentation titled "Predictive Policing Tacoma Overview Deck (2012 July)" obtained via public records request from the Tacoma police department.

Image: A screenshot from a slide presentation titled "Predictive Policing Tacoma Overview Deck (2012 July)" obtained via public records request from the Tacoma police department. The PredPol document titled "How predictable is crime," and presented to the city of Tacoma, WA, gives an overview of how the PredPol draws up boxes that predict where and when crime will occur.

"PredPol's boxes are chosen using only the what, when, and where of incidents that have already occurred in your city," the document reads. "We take anywhere from 3-10 years of crime data and run the relevant points of information through our algorithm. Long and short term trends, recurring events, and environmental factors are all taken into account."

The documents obtained by Motherboard show that officers can use PredPol to select which type of crime that they want to "Look for," such as vandalism or graffiti, disorderly conduct, or commercial or vehicle burglary. PredPol then generates an annotated map (integrated with Google Maps) which shows the officer where it believes such crimes will occur.

For instance, in a document obtained from the Modesto police department by Motherboard, an image shows that an officer that is "looking for" instances of burglary and disorderly conduct is directed to a particular home address. A description reads, "In the past 180 days: 4 Assaults, 3 Drugs, 30 Burglaries, 42 Disorderly Conducts."

In most cities, individual police officers have a great deal of agency over which crimes they want to pursue, and who they want to arrest. Even without the use of predictive technology, police departments have demonstrated that the biases of individual officers can be exacerbated in vulnerable situations, often at the expense of people of color. According to a statistical analysis of the US Police-Shooting Database, police shootings between 2011 and 2015 were 3.49 times more likely on average to target black individuals compared to white, and in certain counties, black individuals were 20 times more likely to be targeted.

Image: Screenshot of Tacoma police department document titled "PredPol_HeatMap Instructions," obtained by Motherboard.

Image: Screenshot of Tacoma police department document titled "PredPol_HeatMap Instructions," obtained by Motherboard. Buttar told Motherboard that it's necessary to consider the potential deadly consequences to the use of algorithmic policing in already overpoliced communities.

"When we talk about secret policing, or corporate contracts using secret algorithms-at the end of the day, we are talking about police, and people die at the hands of police every day in the United States," Buttar said. "The consequences could not be more severe. I can't think of a more compelling case for public oversight, and where it hasn't happened through the institutional political arena."

A Discriminatory Policing MethodPredpol encouraged law enforcement to focus on "broken windows policing," which is based on a non-scientific editorial published in The Atlantic in 1982, which argued that heavily punishing petty crime like graffiti is effective in widespread crime reductions in cities. In the mid 1980s, major cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Boston began to institutionally implement broken windows policing by prosecuting crimes such as public urination or intoxication as criminal rather than civil offenses.

In an email to Motherboard, PrePol's MacDonald said that broken windows was a part of the PredPol "best practices guide" from 2012 to 2014. "Since that time, several studies have been published that indicate that broken windows policing as practiced had an uncertain impact on crime reduction and was viewed by some communities as unfair," MacDonald said. "We removed this from our best practices guides in about 2015."

However, a comprehensive report released by the New York City Department of Investigation in 2016 found that broken windows quite plainly doesn't work. "No evidence was found to support the hypothesis that quality-of-life enforcement has any impact in reducing violent crime," the report reads.

There's a difference between increasing the number of arrests in a city and actually reducing crime. Instead, a "broken windows" model of policing could result in the over-patrolling of communities of color that are already heavily monitored by police via street cameras, social media surveillance, and in some cases, aerial surveillance.

Later in 2016, New York City passed the Criminal Justice Reform Act, a series of criminal reforms that prosecuted petty crimes less severely. But even if cities try to step away from "broken windows" policing, predictive policing technology gives individual officers and police departments the tools to make it the de facto mode of law enforcement.

Ferguson said that police departments are consistently not transparent about when new technology is implemented, nor about the effectiveness of this technology. "I don't know the the reason why there hasn't been more transparency around predictive policing-I think there should be," Ferguson said. "I think police generally haven't valued transparency with new technologies the way they should."

Predpol's MacDonald told Motherboard in an email that it doesn't disclose "confidential metrics" including customer lists "for competitive reasons."

"Some of our customers (like LAPD or Modesto PD) are happy to talk about their use of PredPol, while most choose not to," he said. "We simply follow their lead regarding disclosure. This is pretty standard for commercial relationships in both the corporate and government world."

But the EFF's Buttar said that secrecy in policing contracts undermines democratic oversight. "When [local government] is reaching secret agreements with corporate data providers using secret proprietary algorithms, that is a betrayal of the public trust," Buttar said. "These kinds of activities should not be subject to secrecy."

As reported by Motherboard in October, the log-in portals for seventeen individual police departments revealed that they had possibly used or were using Predpol services. The documents obtained via FOIA requests confirms that severn of these police departments-South Jordan, Modesto, Livermore, Merced, Tacoma, El Monte, and University of California, Berkeley-had or have contracts with PredPol. The contracts indicate relationships with PredPol as early as 2013. Contracts with the cities of Modesto, Merced, and the University of California, Berkeley are currently active.

The fact that that Palo Alto, Merced, and the University of California, Berkeley had or have contracts with PredPol was previously unreported. PredPol's relationships with other cities-such as Haverhill, El Monte, Livermore, Mountain View, Tacoma, and Atlanta-were not well publicized. PredPol blogs or a brief mentions in a local news reports were the only reports that indicate the cities used PredPol.

The privatization of public safety Image: Modesto PredPol documents, obtained by Motherboard.

Image: Modesto PredPol documents, obtained by Motherboard. According to contracts obtained my Motherboard, a contract can cost as little as $4,500 per year. The most expensive contract Motherboard saw was for $120,000 for a three-year contract for the city of Tacoma. The contracts for several cities-such as South Jordan, Mountain View, Palo Alto, Atlanta, Tacoma, and El Monte-were less recent, and appear to have ended between 2014 and 2016. A spokesperson for the Atlanta Police Department told Motherboard in a Muckrock DM that the city had a contract with PredPol between 2013 and 2016.

"You are relying on a new technology to help you do the ordinary business of policing."

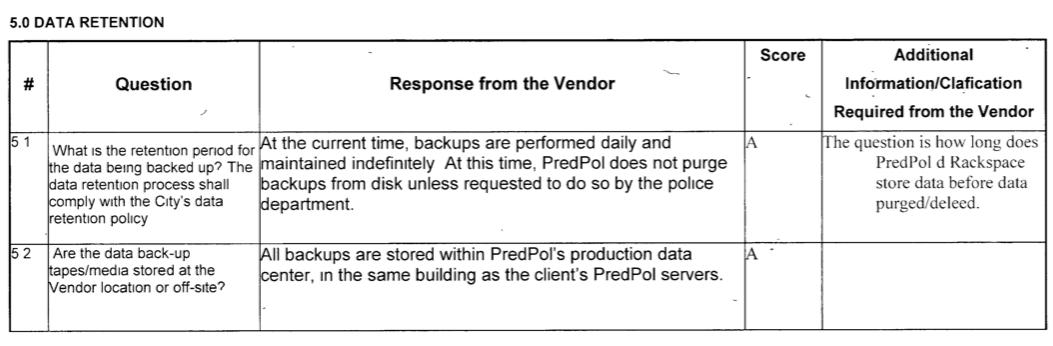

The documents obtained by Motherboard also shed light on PredPol's former data storage practices. According to an agreement document between the city of Palo Alto and Predpol dated August of 2013, PredPol performs daily backups which are kept indefinitely on servers owned by the cloud computing company Rackspace. In an email to Motherboard, PredPol's MacDonald said that the company currently does not use Rackspace servers.

Image: Palo Alto police department "Vendor Information Security Questionnaire" for PredPol, obtained via public record request by Motherboard.

Image: Palo Alto police department "Vendor Information Security Questionnaire" for PredPol, obtained via public record request by Motherboard. "At this time, Predpol does not purge backups from disk unless requested to do so by the police department," the document reads.

According to software configuration data obtained by Motherboard for the city of Merced, the nature of the data stored by PredPol on Rackspace is highly sensitive. It includes the exact location/address, date, and time of the crime, a description of the crime that occurred, and other data points.

Image: Merced police department's PredPol software configuration file, obtained obtained via public records request by Motherboard.

Image: Merced police department's PredPol software configuration file, obtained obtained via public records request by Motherboard. According to Ferguson, the more sensitive the data, the greater the risk in entrusting that data to a private company. "For some types of data, there's a real risk of both security and privacy issues-but also with making sure that the city controls it," Ferguson said. "So if you're a company...you're collecting an incredible amount of unstructured data that you could structure and use and sell."

Rackspace's privacy statement bans third party data sharing. However, it's unclear whether PredPol has the authority to share data stored on Rackspace with third parties, or if the relevant police department or municipality need to provide permission first. Rackspace did not respond to Motherboard's request for comment.

PredPol isn't unique in its position as a private company that has quietly become instrumental in the day-to-day functioning of police departments around the country. Ferguson told Motherboard that across the country, there's been a shift toward the privatization of public safety.

"You are relying on a new technology to help you do the ordinary business of policing, which means you lose some control over how it gets done," Ferguson said. "You have to rely on technical experts that may not be in house to really run your police department, which is a problem because of public accountability and different incentives."

"I think that what we're seeing in this policing tech space is the beginning of a race to become the policing platform," Ferguson added. "You're seeing the economic and financial race to become the platform for policing, recognizing that if you become the platform in the data, you win, because everything goes through you."