Netflix Has Saved Every Choice You’ve Ever Made in ‘Black Mirror: Bandersnatch'

When you gaze into Black Mirror's Bandersnatch, it also gazes into you. It's no secret that Netflix tracks what its users watch and how long they watch it, but Bandersnatchgave Netflix a unique opportunity to let the streaming giant learn what its users wanted in real time. Some people even speculated that Bandersnatch was largely a data-harvesting operation.

Michael Veale, a technology policy researcher at University College London, wanted to know what data Netflix was collecting from Bandersnatch. "People had been speculating a lot on Twitter about Netflix's motivations," Veale told me in an email. "I thought it would be a fun test to show people how you can use data protection law to ask real questions you have."

The law Veale used is Europe's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The GDPR granted EU citizens a right to access-anyone can request a wealth of information from a company collecting data. Users can formally request a company such as Netflix tell them the reason its collecting data, the categories they're sorting data into, third parties it's sharing the data with, and other information.

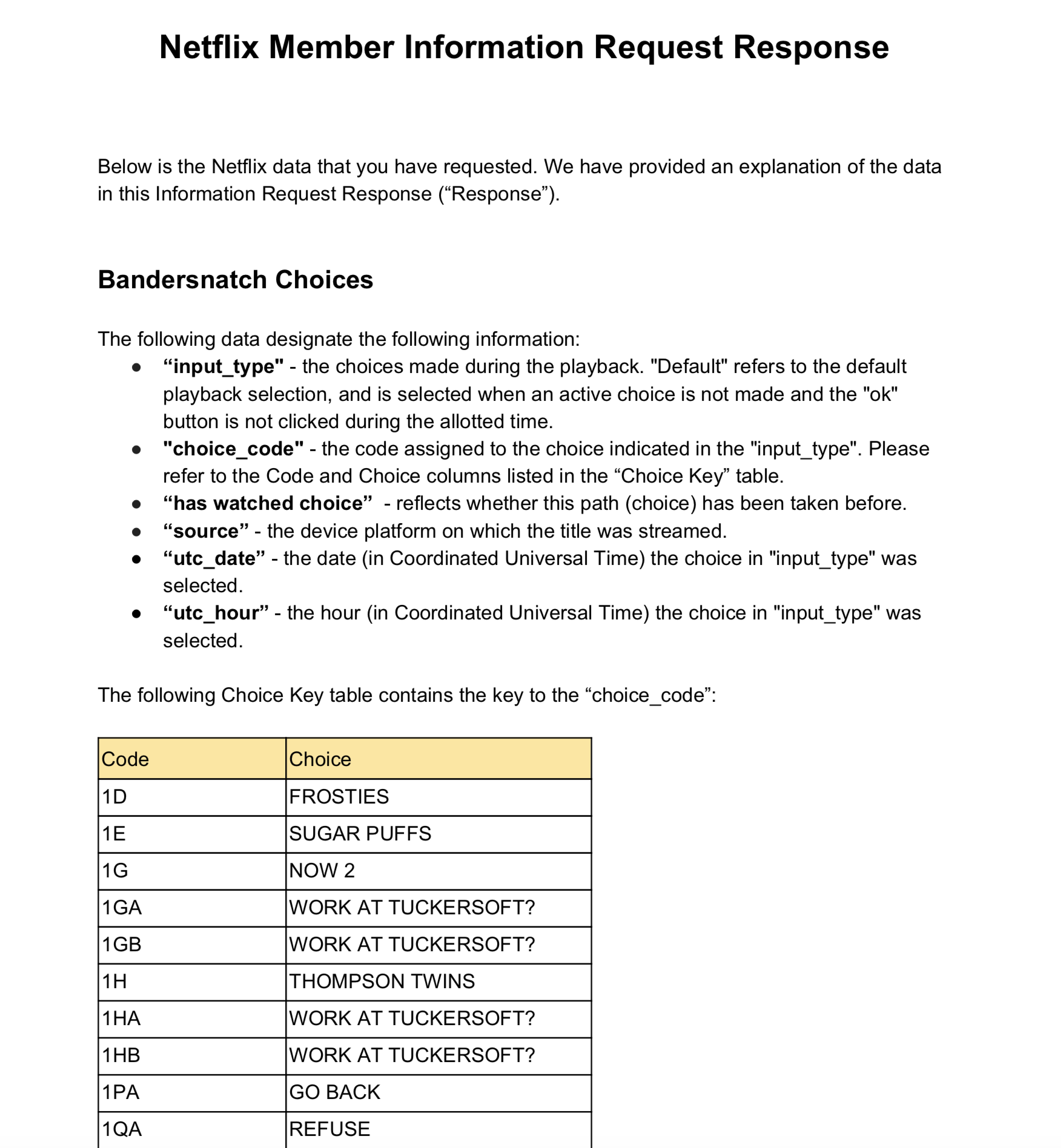

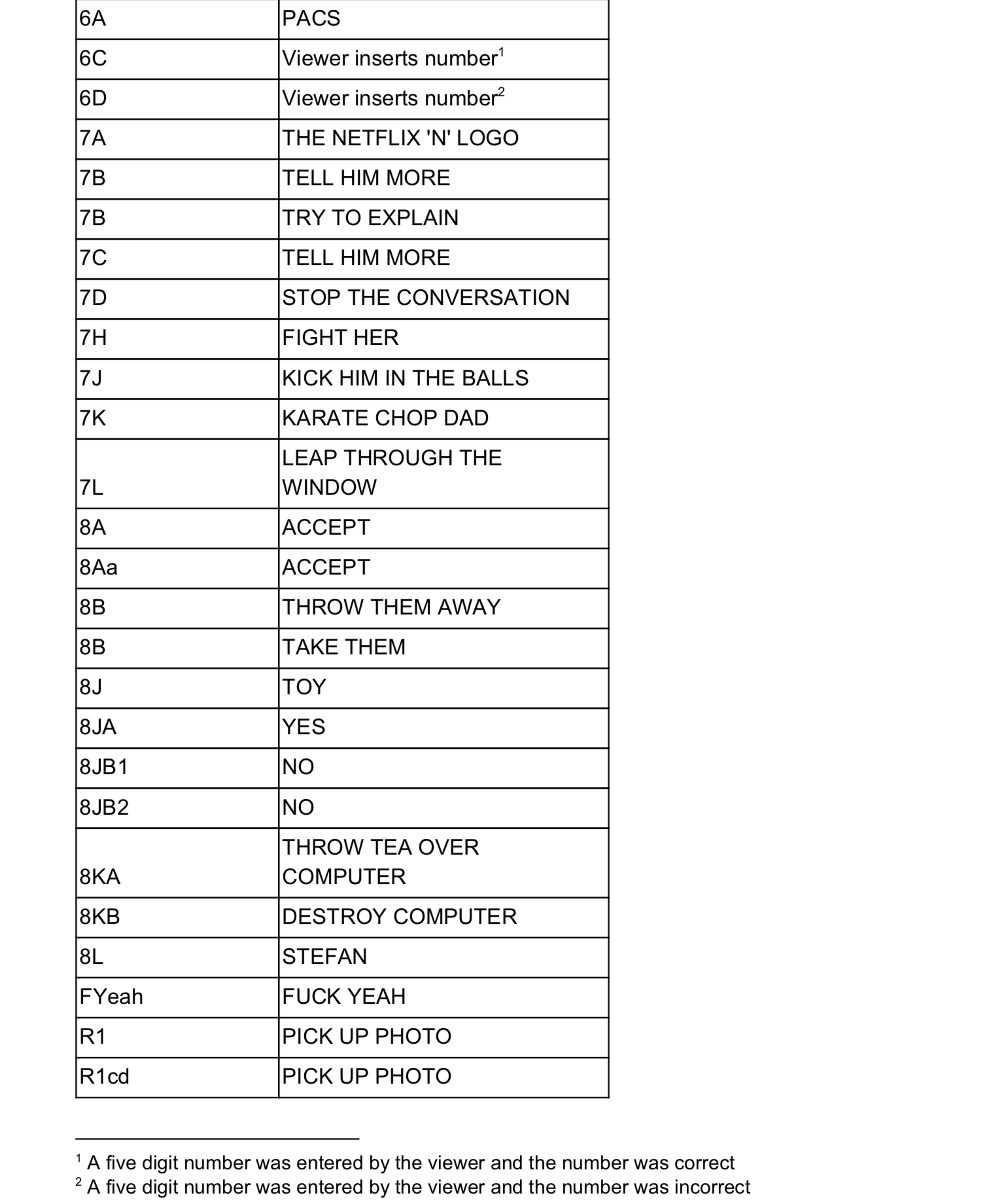

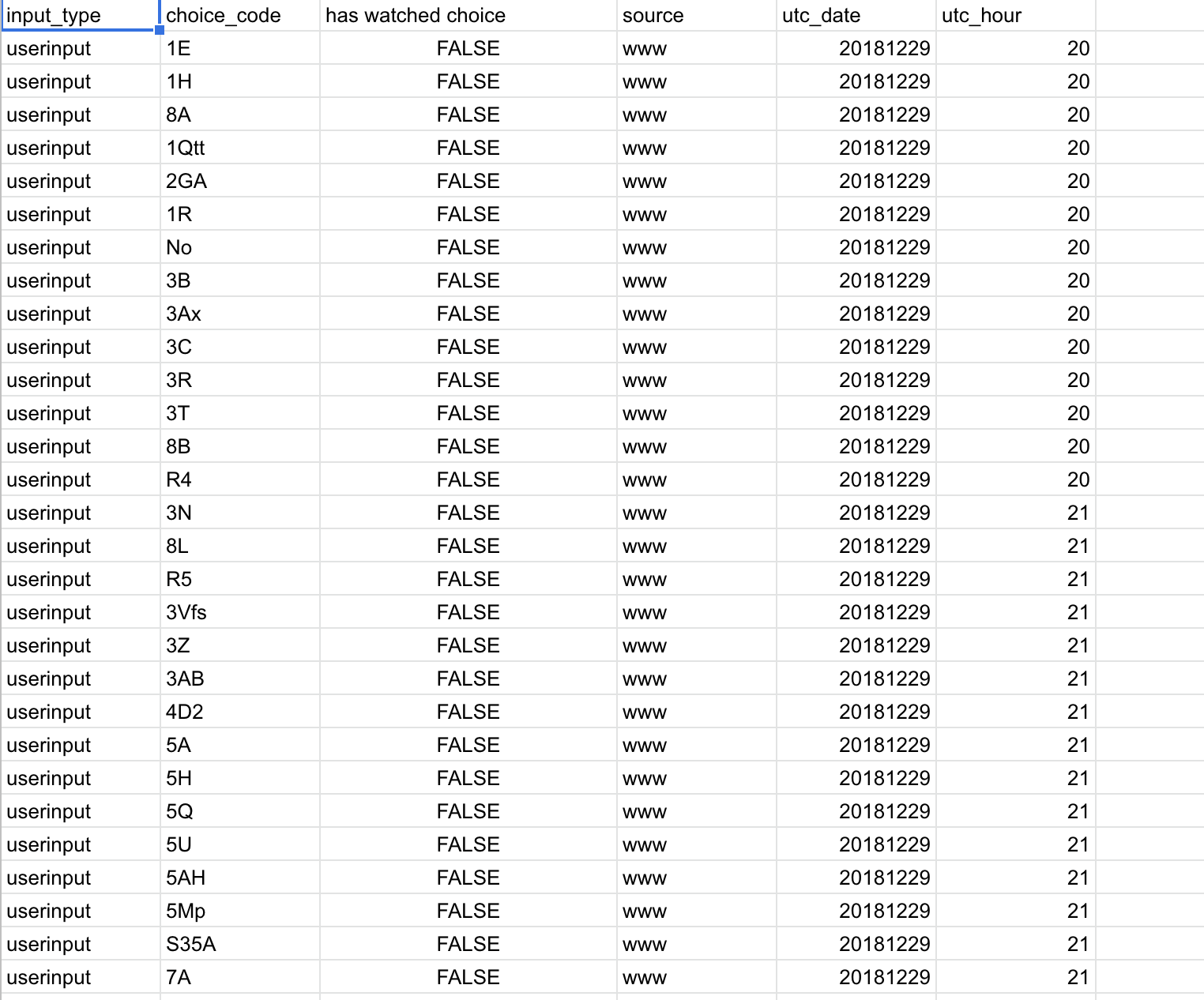

Veale used this right of access to ask Netflix questions about Bandersnatch and revealed the answers in a Twitter thread. He found that Netflix is tracking the decisions its users make (which makes sense considering how the film works), and that it is keeping those decisions long after a user has finished the film. It is also stores aggregated forms of the users choice to "help [Netflix] determine how to improve this model of storytelling in the context of a show or movie," the company said in its email response to him. The .csv and PDF files displayed Veale's journey through Bandersnatch, every choice displayed in a long line for him to see.

Veale told me that requesting the data was as easy as sending Netflix an email, but the specifics of getting the information he want were complicated. The GDPR right to access request works a lot like America's Freedom of Information Act requests-the applicant needs to be very specific to get what they want. After sending along a copy of his passport to prove his identity, Veale got the answers he wanted from Netflix via email and-in a separate email-a link to a website where he downloaded an encrypted version of his data. He had to use a Netflix-provided key to unlock the data, which came in the form of a .csv file and a PDF.

"It was tricky, as I had to ask these questions specifically," Veale told me in an email. "It's unclear if this is included by default in requests to get your data from Netflix or not-I can tell you often this kind of specific data is not included when you ask for 'all your data.' Knowing what 'all your data' is, and what the company's definition of 'all your data' does not include, is most of the challenge."

Veale also said it's possible the only reason Netflix played so nice with him is because he's a public figure known for using GDPR to get data out of big tech companies. Colleagues doing similar studies "just got told to get lost, or even had their accounts deleted for being troublemakers" by other companies, he said.

Veale is concerned by what he learned. Netflix didn't tell Veale how long it keeps the data and what the long term deletion plans are.

"They claim they're doing the processing as it's 'necessary' for performing the contract between me and Netflix," Veale told me. "Is storing that data against my account really 'necessary'? They clearly haven't delinked it or anonymised it, as I've got access to it long after I watched the show. If you asked me, they should really be using consent (which you should be able to refuse) or legitimate interests (meaning you can object to it) instead."

Ultimately, Bandersnatch may seem safe, but what data Netflix scraped from its viewings, how that data is stored, and for how long are all questions users deserve to know. And training ourselves to ask questions of companies like Netflix also trains us to ask the same of companies like Facebook and Google.

"I'm hoping it inspires people to reach to their rights in situations like these, and to normalise them," Veale said. "When companies get more and more requests, they'll have to streamline them for the sake of economising, and that in turn will benefit all users."