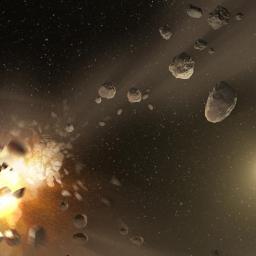

A Meteor More Powerful Than 10 Atomic Bombs Exploded Over the Bering Sea

A meteor that exploded over the Bering Sea in December released 10 times the energy of an atomic bomb into the atmosphere.

The asteroid, which was about 10 meters wide, disintegrated in the skies off the coast of Russia's Kamchatka peninsula on December 18. It unleashed 173 kilotons of energy, making it the second-biggest fireball in recent decades next to the 440-kiloton meteor that rocked the Russian city of Chelyabinsk on February 15, 2013.

Unlike the Chelyabinsk event, the Bering Sea fireball did not make a big news splash immediately after it impacted in part because it occurred over a remote and unpopulated area. Chelyabinsk, in contrast, is home to more than one million people, many of whom witnessed or were injured by the explosion. Some even captured the dazzling airburst on camera, which instantly enabled viewers around the world to share the sight of the blast.

The Bering Sea meteor was initially detected by US Air Force satellites, as well as decades-old infrasound stations that are designed to flag potential nuclear detonations. It took a few months before NASA's Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS), which tracks hazardous objects near our planet, logged the airburst on its map of fireballs.

"There's a good deal of manual processing that has to occur of that data before it's put in a form to be reported to NASA," Lindley Johnson, NASA's Planetary Defense Officer, told Motherboard over the phone. "The reports that we get in from these events can vary anywhere from a few hours to several weeks."

"As you can well imagine, it's in a sensitive part of the world too, so it just took a little longer for it to make it through all the processes that this information has to go through before it's released to NASA for public release," he added.

Word of the fireball began to spread after Peter Brown, a meteor specialist at Western University in Canada, tweeted about the infrasound detections of the airburst on March 8.

Brown pointed out that extremely energetic impacts like this occur once every few decades on average.

Scientists have made huge strides in tracking potentially hazardous Near Earth Objects (NEOs) in recent decades, but both the Bering Sea and Chelyabinsk meteors remained off the grid until they exploded.

Fortunately, most space rocks that collide with Earth burn up in the atmosphere and only produce a small amount of debris that reaches the ground (such as the Chelyabinsk meteorite).

"Our regular ground-based surveys do pick up some of these very small objects as they pass us by, or after they've passed us," said Kelly Fast, NASA's Near-Earth Object Observations program manager, in a phone call with Motherboard. "They tend to be right upon us by the time they're seen but when they're that small, the atmosphere will take care of it if it's something that would impact."

Unusually large airbursts can deal some damage on the ground, though this is rare. The shockwave and flash from Chelyabinsk meteor caused injuries such as temporary blindness and wounds from shattered glass and collapsing structures.

But even that meteor has nothing on the most energetic airburst on record-the Tunguska event of June 1908.

Read More:This Asteroid Hunter Is Tasked With Saving Earth from Killer Impacts

That blast is estimated to have released 10 to 15 megatons of energy, flattening hundreds of square miles of forest around the Podkamennaya Tunguska river in Siberia. There were no confirmed deaths, but the specter of such a massive airburst is one reason why scientists continue to develop better observatories for tracking and cataloguing potentially dangerous space rocks.

Update: This article has been updated to include comments from NASA experts Lindley Johnson and Kelly Fast.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every dayby signing up for our newsletter.