Researchers Find Google Play Store Apps Were Actually Government Malware

Hackers working for a surveillance company infected hundreds of people with several malicious Android apps that were hosted on the official Google Play Store for months, Motherboard has learned.

In the past, both government hackers and those working for criminal organizations have uploaded malicious apps to the Play Store. This new case once again highlights the limits of Google's filters that are intended to prevent malware from slipping onto the Play Store. In this case, more than 20 malicious apps went unnoticed by Google over the course of roughly two years.

Motherboard has also learned of a new kind of Android malware on the Google Play store that was sold to the Italian government by a company that sells surveillance cameras but was not known to produce malware until now. Experts told Motherboard the operation may have ensnared innocent victims as the spyware appears to have been faulty and poorly targeted. Legal and law enforcement experts told Motherboard the spyware could be illegal.

"These apps would remain available on the Play Store for months and would eventually be re-uploaded."

The spyware apps were discovered and studied in a joint investigation by researchers from Security Without Borders, a non-profit that often investigates threats against dissidents and human rights defenders, and Motherboard. The researchers published a detailed, technical report of their findings on Friday.

"We identified previously unknown spyware apps being successfully uploaded on Google Play Store multiple times over the course of over two years. These apps would remain available on the Play Store for months and would eventually be re-uploaded," the researchers wrote.

Lukas Stefanko, a researcher at security firm ESET, who specializes in Android malware but was not involved in the Security Without Borders research, told Motherboard that it's alarming, but not surprising, that malware continues to make its way past the Google Play Store's filters.

"Malware in 2018 and even in 2019 has successfully penetrated Google Play's security mechanisms. Some improvements are necessary," Stefanko said in an online chat. "Google is not a security company, maybe they should focus more on that."

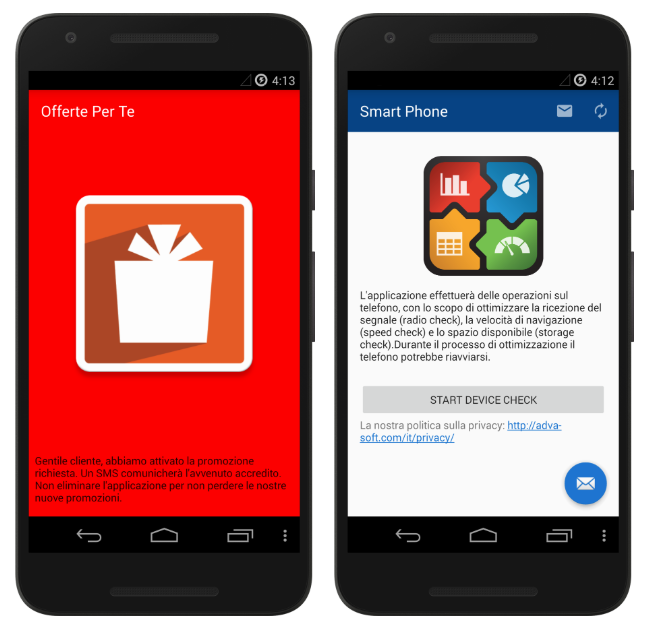

MEET EXODUSIn an apparent attempt to trick targets to install them, the spyware apps were designed to look like harmless apps to receive promotions and marketing offers from local Italian cellphone providers, or to improve the device's performance.

A screenshot of one of the malicious apps. (Image: Security Without Borders)

A screenshot of one of the malicious apps. (Image: Security Without Borders)The researchers alerted Google earlier this year to the existence of the apps, which were then taken down. Google told the researchers and Motherboard, that it found a total of 25 different versions of the spyware over the last two years, dating back to 2016. Google declined to share the exact numbers of victims, but said it was below 1,000, and that all of them were in Italy. The company would not provide more information about the targets.

The researchers are calling the malware Exodus, after the name of the command and control servers the apps connected to. A person who's familiar with the malware development confirmed to Motherboard that was the internal name of the malware.

Exodus was programmed to act in two stages. In the first stage, the spyware installs itself and only checks the phone number and its IMEI-the device's unique identifying number-presumably to check whether the phone was intended to be targeted. For that apparent purpose, the malware has a function called "CheckValidTarget."

But, in fact, the spyware does not appear to properly check, according to the researchers. This is important because there are currently some legally permissible uses of narrowly targeted malware-for example, with a court order, law enforcement can legally hack devices in many countries.

In a test done on a burner phone, the researchers saw that after running the check, the malware downloaded a ZIP file to install the actual malware, which hacks the phone and steals data from it.

"This suggests that the operators of the Command & Control are not enforcing a proper validation of the targets," Security Without Borders concluded in the report. "Additionally, during a period of several days, our infected test devices were never remotely disinfected by the operators."

Got a tip? You can contact Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, OTR chat at lorenzofb@jabber.ccc.de, or email lorenzo@motherboard.tv. And you can reach Riccardo Coluccini securely on OTR chat at rcoluc@jabber.ccc.de, and riccardo.coluccini@vice.com.

At that point, the malware has access to most of the sensitive data on the infected phone, such as audio recordings of the phone's surroundings, phone calls, browsing history, calendar information, geolocation, Facebook Messenger logs, WhatsApp chats, and text messages, among other data, according to the researchers.

The spyware also opens up a port and a shell on the device, meaning it allows the operators to send commands to the infected phone. According to the researchers, this shell is not programmed to use encryption, and the port is open to anyone on the same Wi-Fi network as the target. This means that anyone in the vicinity could hack the infected device, according to the researchers.

"This inevitably leaves the device open not only for further compromise but for data tampering as well," the researchers wrote.

A second, independent analysis by Trail of Bits, a New York-based cybersecurity company that looked into the malware for Motherboard, confirmed that the malware samples all connect to the servers of one company, that the IP addresses identified by Security Without Borders are all connected, and that the malware leaves the target device more vulnerable to hacking.

WHO IS BEHIND THE SPYWARE?

All the evidence collected by Security Without Borders in its investigation indicates the malware was developed by eSurv, an Italian company based in the southern city of Catanzaro, in the Calabria region.

The first hint that the authors of the malware were italian came from two strings inside the malware code: "mundizza," and "RINO GATTUSO." Mundizza is a dialectal word from the southern region of calabria that loosely translates to garbage. Rino Gattuso is a famous retired Italian footballer from Calabria.

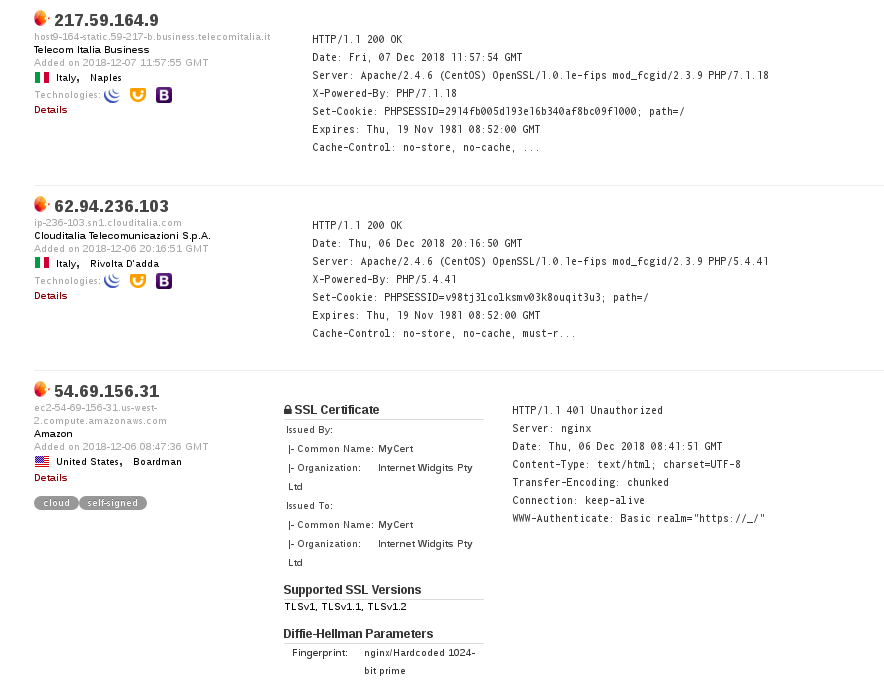

The real smoking gun, however, is the command and control server used in several of the apps found on the Play Store to send the data back to the malware operators.

The server, according to the researchers, shares a TLS web encryption certificate with other servers that belong to eSurv's surveillance camera service, which is the company's main public business. Also, some of these servers identified by the researchers display eSurv's logo as the icon associated with the server's address, the icon you can see in your browser's tab, also known as favicon.

Other spyware samples communicate with a server belonging to eSurv, according to the researchers. Google confirmed the servers belong to eSurv. The Trail of Bits researcher who reviewed the technical report and the spyware confirmed that it's linked to eSurv.

A sample of eSurv's command and control servers. (Image: Security Without Borders)

A sample of eSurv's command and control servers. (Image: Security Without Borders) Finally, an eSurv employee explained in a resume publicly available through his LinkedIn page that as part of his job at the company, he developed "an 'agent' application to gather data from Android devices and send it to a C&C server"-a technical, albeit clear, reference to Android spyware.

Motherboard reached out to the developer, who declined to comment, arguing that the answer would be "confidential information. I don't think I can say anything about this ;)"

We reached out to eSurv multiple times via email and LinkedIn. Initially, an employee of the company claimed to be surprised and shocked by our findings, given that eSurv only sells video surveillance, she said. A few hours after our phone call, the company took down its site for a couple of weeks.

After we followed up and asked for clarification, the company declined to comment.

eSurv appears to have an ongoing relationship with Italian law enforcement, though Security Without Borders was unable to confirm whether the malicious apps were developed for government customers.

eSurv won an Italian government State Police tender for the development of a "passive and active interception system," according to a document published online in compliance with the Italian government spending transparency law. The document reveals that eSurv received a payment of a 307,439.90 on November 6, 2017.

We filed a freedom of information request to obtain information on the tender, the list of companies that participated, the technical offer sent by the company, and the invoices issued by eSurv. Our request, however, was rejected. The Anti-Drug Police Directorate, an agency within the State Police which responded to the request, said it could not respond with the documents because the surveillance system was obtained with "special security measures."

Over the last few months, several sources with knowledge of Italy's spyware market told Motherboard that a new company from Calabria was getting several contracts to develop surveillance software with law enforcement and government agencies. Some of those sources specifically named eSurv as that new company that was taking the local market by storm.

Finally, a source close to eSurv, who asked to remain anonymous because he was not authorized to speak to the press, said that the company sells malware to the Italian police.

"They publish [the spyware] on the Play Store and then induce the person to download it and open it," the source said in an online chat.

IS THIS ALL LEGAL?Using spyware with warrants or a judge's authorization is, generally speaking, legal in most countries in Europe, as well as the United States. In this case, however, eSurv's spyware may not be operating according to the law, experts told Motherboard.

"I don't think there are reasons to believe this spyware is legal," Giuseppe Vaciago, an Italian lawyer who specializes in criminal law and surveillance, told Motherboard after reviewing the report by Security Without Borders.

Vaciago explained that a spyware acting according to Italian law should not install itself on any target without first validating that the target is legitimate, something Exodus does not properly do, according to the researchers.

Moreover, Vaciago explained that Italian law effectively equates spyware with physical surveillance devices, such as old school hidden microphones and cameras, limiting its uses to capturing audio and video.

"This software, on the other hand, is able to do, and effectively appears to have done, much more invasive activities than those prescribed by the law," Vaciago told Motherboard in an email.

"Opening up security holes and leaving them available to anyone is crazy and senseless, even before being illegal."

The fact that the malware leaves the device vulnerable to other hackers is perhaps the worst element of Exodus, according to a police agent who has experience using spyware during investigations, and who asked to remain anonymous because he's not allowed to speak to the press.

"This, from the point of view of legal surveillance, is insane," the agent told Motherboard. "Opening up security holes and leaving them available to anyone is crazy and senseless, even before being illegal."

At the end of 2017, Italy introduced a law regulating the use of spyware for law enforcement activities and investigations-the law only regulates the use of spyware to record audio remotely, leaving out all the other features that surveillance software can have, such as intercepting text messages, or taking screenshots of the screen. In May 2018, the Ministry of Justice published technical requirements that must be respected in the development and use of spyware by law enforcement agencies.

In an opinion issued by the Italian Data Protection Authority in April of last year, the authority criticized the requirements for being too vague when it came to describing the interception system's components, and it emphasized that authorities need to ensure that installing the spyware on a target does not reduce the overall security of the infected device.

"This is in order to prevent the device from being compromised by third parties, avoiding negative consequences on the protection of personal data contained therein as well as on investigative activities," the authority wrote.

Apps that offer promotions and marketing offers from local telecommunication providers is a front that has been used by Italian government malware before. In fact, Italian telecommunication companies can be forced by the government to send text messages to facilitate malware injection on suspects' devices, as previously reported by Motherboard Italy.

Details of this activity were found in a hearing of the Company Security Governance of the Italian cellphone provider Wind Tre Spa, held in March of 2017 by the Parliamentary Committee for the Security of the Republic (COPASIR)-a committee that supervises the activity of the intelligence services.

According to the document, which summarizes the hearings, when it comes to the use of spyware for investigations, the telecommunication operators are consulted to facilitate the infection of third party devices with the malware. These operations "consist mainly in expanding the bandwidth and sending messages to request certain maintenance activities," the document reads. These activities may be included in what are called "mandatory justice services" for telecommunication operators, services that are detailed in a specific price list by the Ministry of Justice: ranging from 15 Euros for wiretaps and internet communication flow, to 110 Euros for "assistance and feasibility studies."

At the time of publication, the Italian State Police did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the technology subject to their tender, nor they had replied to questions on the use of this spyware. Questions to two Italian Public Prosecutor's Offices went unanswered as well.

The police agent agreed that eSurv's spyware lacked the right scope and safeguards to ensure it wouldn't hit people who were not being under investigation.

"You can't do something indiscriminate," the police agent told Motherboard. "Putting something on the Play Store thinking you're going to infect an undetermined number of people, and do trawling is something absolutely illegal."

The source close to eSurv confirmed that, at times, the apps ended up on the wrong phones, as "oblivious people," the source said, "unknowingly downloaded the app and infected themselves."

Instead of doing anything to stop that, however, the company used the victims as "guinea pigs."

Listen to CYBER, Motherboard's new weekly podcast about hacking and cybersecurity.