Visiting the City That Built the Hanford Nuclear Site

As my plane approaches the Tri-Cities Airport in south-central Washington state, the sandy expanse outside my window gives way to hundreds of bright green circles and squares. From this semi-arid terrain springs an irrigated oasis of potatoes, hops, peaches, and sweet corn. Just beyond our view is one of the most contaminated places in the world: the Hanford Site, home to 177 aging tanks of radioactive waste.

I've come to Richland, Wash., to report on the monumental effort to glassify" tank waste, encase it in stainless steel, and bury it in trenches or a deep geologic repository. After 30 years of planning and building, the U.S. Department of Energy is finally on the cusp of treating the sludge, which engineers created while producing some 60,000 nuclear weapons-including the atomic bomb that razed Nagasaki, Japan, in 1945. If all goes to plan, the multibillion-dollar cleanup should conclude in roughly 60 years. [See A Glass Nightmare: Cleaning Up the Cold War's Nuclear Legacy at Hanford."]

My five-day visit in July 2019 is a study in contrasts. Crops and vineyards fed by three yawning rivers grow near the boundaries of a barren nuclear waste site. Officials and experts assure me that the air and water in surrounding communities is safe, that the public is protected. But the dosimeters mounted to walls and clipped to Hanford workers' badges are constant reminders of the region's toxic legacy. I meet longtimers who are unflinchingly proud of their city's place in history and newcomers who know relatively little about the shuttered reactors (and sludgy mess) just miles from their backyards.

Hanford is a national enterprise, built in the name of national security. Yet beyond this sliver of the Pacific Northwest, many Americans likely don't even know it exists.

Photo: Maria Gallucci A poster advertises Atomic Frontier Day celebrations at Howard Amon Park in Richland, Wash.

Photo: Maria Gallucci A poster advertises Atomic Frontier Day celebrations at Howard Amon Park in Richland, Wash. In the Richland area, Hanford permeates the local culture. The city was literally built to support Hanford's construction. At the airport, the couple waiting behind me at the rental car kiosk strikes up a conversation, offering local tips. I mention my assignment, and they laugh at the word Hanford." In that case, they say, I should certainly visit 3 Eyed Fish, a restaurant in Richland. The owner has described the name as an inside joke," exemplifying the kind of dark humor that prevails in a place with an inconvenient past.

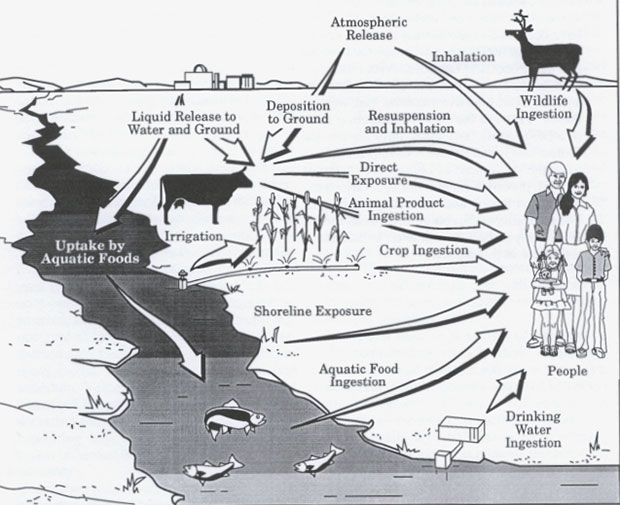

Image: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention An illustration in a 1994 U.S. government report shows potential pathways to exposure.

Image: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention An illustration in a 1994 U.S. government report shows potential pathways to exposure. Along with toxic waste, thousands of residents in the Richland area were exposed to radioactive releases from Hanford from 1944 to 1971. More recently, in 2017, dozens of workers at the site inhaled or ingested radioactive particles while demolishing a plutonium finishing plant. Still, it's not unusual to see T-shirts with slogans like Hanford Worker: In Case of Blackout Stand Next to Me" or Richland: Glowing Since 1943," the year construction at Hanford began.

My first stop isn't at the cheeky restaurant but the B Reactor, the world's first large-scale plutonium production complex. Diligently preserved, it sits on a remote corner of the Hanford Site, past sagebrush-covered hills and a large facility that makes frozen French fries. [For more on that, see my article, Visit the Reactor That Made the Plutonium for the Fat Man' Nuclear Bomb."]

Photos: Maria Gallucci Top: A letterman jacket is on display at the gift shop adjoining the B Reactor visitor center in Richland, Wash. Bottom: Craft breweries around Richland, Wash., use nuclear iconography in a nod to the nearby Hanford Site.

Photos: Maria Gallucci Top: A letterman jacket is on display at the gift shop adjoining the B Reactor visitor center in Richland, Wash. Bottom: Craft breweries around Richland, Wash., use nuclear iconography in a nod to the nearby Hanford Site. In the museum's gift shop, the souvenirs are more celebratory than sardonic. The owner has hung her daughter's high school jacket on the wall; a felt mushroom cloud explodes over the mascot name, Bombers. We're not politically correct around here," she jokes, noting that her parents had worked at the B Reactor. To her, the facility meant jobs and food on the table. I buy a refrigerator magnet but decline a vial of nuclear-grade graphite, a material used to build Hanford's first reactors.

Out the door, I pass the Bombing Range Brewing Co., a craft brewery whose logo is a nuclear warhead made from green hops. At a park overlooking the Columbia River, posters advertise Atomic Frontier Day festivities to mark the 75th anniversary of the Manhattan Project. The secretive initiative had kickstarted U.S. nuclear weapons production during World War II, transforming this region's homesteads and sacred Native American sites into the sprawling contaminated complex that remains today.

I cap off my last night in Richland with a visit to 3 Eyed Fish. The restaurant is pleasant and normal; no fluorescent green cocktails are on the menu. Not far from here, toxic chemicals and radionuclides sit below ground in corroding, decades-old tanks. Workers treat groundwater tainted with hexavalent chromium and demolish still-radioactive buildings. Somehow, as I sip a glass of the house red wine, that feels a world away.