Proposed modal integration policy would dismantle the Bicycle Master Plan

Seattle's Complete Streets ordinance turns 14 years old this year. Since becoming one of the first major American cities to codify in city law the idea that all major transportation improvements should include accommodations for all types of street users, the city has struggled to actually put this into practice. Loopholes allowed individual projects to be exempt from the ordinance. In 2019, after SDOT made it crystal clear how toothless the ordinance was by completing a Complete Streets checklist on 35th Ave NE in Wedgwood (after the department redesigned the street to include no bike facilities at the direction of the Mayor), the City Council passed another law requiring major repaving projects to include bike facilities if they are designated on the Bicycle Master Plan.

Now, it looks like the Seattle Department of Transportation is ready to throw in the towel on the Bicycle Master Plan entirely, and along with it all of the plan's goals and benefits, under the guise of integrating all of the City's modal plans together.

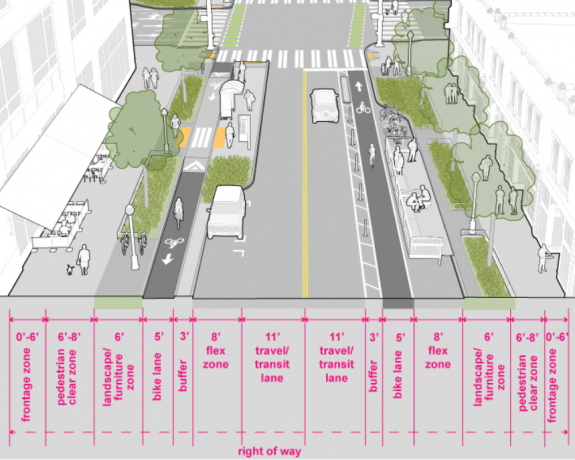

Last Thursday SDOT held its final meeting with the Policy and Operations Advisory Group (POAG) and presented a finalized draft modal integration policy framework". We previewed this framework after the group's last meeting in December. According to the department, it was developed to create policy guidance on integrating the bicycle, transit, freight, and pedestrian master plans. It focuses on areas where the right of way is deficient", meaning that according to SDOT's own design standards (as laid out in its Streets Illustrated Right-of-Way improvement manual) there isn't enough room to accommodate all modes on a specific city block. Even with a large policy foundation, we lack comprehensive policy guidance for how accommodate these networks in places where the [street] is too narrow for all desired modes and uses," the policy's executive summary states.

An image of street space allocation as recommended by the Streets Illustrated manual.

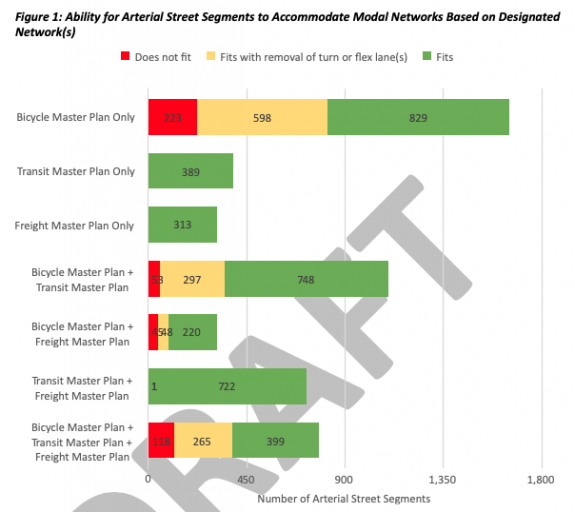

That executive summary, which is the most detailed summary of the policy that we've seen so far, makes it even more clear that the adoption of this policy would specifically target the Bicycle Master Plan over the other modal plans. Across the three adopted modal plans (with the Pedestrian Master Plan analyzed separately), it cites 5,269 segments of bike lane, transit lane, or freight lane intended to fit within the space available from one curb to another. SDOT says 8% of them, or 440 blocks, are not wide enough to accommodate all of the modes specified as needing space in their respective plans. Amazingly, all but one of those 440 includes a planned bike facility. On half of those blocks (223), the bicycle facility is the only thing even competing for extra street space- no transit lanes or freight lanes are even conceived on those blocks.

In other words, if the Bicycle Master Plan didn't exist, there would be one block of conflict between Seattle's modal plans over the use of the curb-to-curb space on our streets.

In addition, there are another 1,208 street segments where a planned bike, freight, or transit lane fits in the street space only if a turn lane or a flex lane (parking, loading, peak hour travel) were removed. Again, this is almost entirely (598 of these) a bike facility all by itself. The policy states that flex lanes in some cases, should be prioritized in right-of-way allocation decisions, and should be evaluated more consistently within concept design processes".

You can see these numbers broken down in a chart produced by SDOT that shows the number of street segments called for in each master plan and whether they fit".

This chart breaks down where SDOT sees conflict between the modal plans, with the Bicycle Master Plan being the biggest source of conflict.

So what would the policy actually do? It would determine a mode that should receive a first bite at the apple, so to speak, in reallocating street space- determined by the land use of the surrounding area. Inside manufacturing and industrial centers, freight lanes would receive priority over a bike facility if only one is determined to fit. Transit lanes would receive priority in areas that are not inside those manufacturing centers or in urban centers or villages. Currently SDOT doesn't have policies that actually lay out when freight or transit lanes are called for, which it says it is developing as a forthcoming policy.

Inside urban villages and centers, pedestrian space would be prioritized. Seattle's current Pedestrian Master Plan doesn't really deal with sidewalk expansion, and so this would be a welcome broadening of the ambitions of that plan. SDOT says that there are 424 segments of streets along arterials where the current sidewalk width is three or more feet from meeting the standards in Streets Illustrated. The policy would preserve flex lanes (most frequently on-street parking) for future expansion, but only inside urban centers and villages.

So where would bike facilities be prioritized? The policy would designate bicycle priority segments that are critical for bicycle connectivity". In other words, a scaled-down Bicycle Plan map would decide which streets are critical to complete and the rest would be dropped off. Of course, this ignores the people would would use that deleted segment to access the citywide network. One of the goals of the 2014 Bicycle Master Plan is to have 100% of households in Seattle within 1/4 mile of an all ages and abilities bicycle facility by 2035.

This map doesn't appear to exist yet. At the meeting, the advisory group was told that SDOT would also be developing a list of criteria that would determine whether a route was critical, and that route directness", aka how far out of the way an alternate route would take someone, would be on that list. Obviously a scaled-down citywide bike map would need to involve a considerable amount of community input.

It's also not clear exactly how bike facilities deemed critical" would actually be prioritized in areas where the policy also says to prioritize other modes. What to do, for example, if a transit lane is recommended on a critical bicycle segment.

But the built-in assumptions that got us to this point, namely that there isn't enough room on our streets to accommodate everyone and the Right-Of-Way design standards that have caused us to arrive at that conclusion, need serious rethinking. The unseen modal plan influencing these decisions is the base map: the amount of street space reserved for personal vehicles. The concept of a Car Master Plan came up quite a bit at the meeting. But without really seeing its influence here, we can't push back on its assumptions. We do know that SDOT did not consider the removal of general purpose lanes entirely on any city street when considering which street widths are deficient- pedestrian streets or bike/transit only streets have not been considered here.

It's pretty clear now the degree to which this plan targets bike facilities to be de-prioritized over almost all others. SDOT wants to fully develop this into a citywide multimodal map to be included in the 2024 Comprehensive Plan update, codifying this gutted bike plan as deeply as it can be in city policy, and use it to influence the next citywide transportation levy. There is very little upside to adopting this policy, and a huge amount of downside.