What’s the deal with BIRT? A conversation

Last fall, SDOT released a report on the future of transportation in the vicinity of Interbay and Ballard. The result, the Ballard-Interbay Regional Transportation System (BIRT) report, focused on the big topics of what to do about the Magnolia and Ballard bridges, both on a timeline to replacement, but it also looked at the projects needed to better enable to get around the area without a car, of which there are many.

There are so many moving pieces around what happens next, we got a few people who have been following the topic closely together and talked about what the BIRT report means and what its impact is likely to be. The discussion ended up venturing into a larger discussion about transportation and land use in Seattle.

In the conversation:

Laura Loe is a NW Queen Anne Renter, a Magnolia P-Patch gardener, and has nervously ridden a bike less than two dozen times.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking of tasks around Ballard. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts experience in planning and law. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it's no longer a weekly obligation.

Mark Ostrow once had a long conversation with Bobby McFerrin at a brasserie in Paris. His tweets, which are legendary, can be found at @qagreenways.

The conversation has been edited for clarity and for length.

Seattle Bike Blog: So, I just want to ask this group what BIRT is, as an introductory question.

Ray: BIRT is...

Laura: A blank check for climate destruction.

Ray: Yeah, exactly.

Laura: It's a blank check for climate destruction!

Ray: BIRT is a study that the state mandated in 2019 that took an entire year for the City of Seattle to write...

Laura: And it was seven hundred thousand dollars.

Ray: And in that year they left out parts of Interbay in order to support rebuilding two billion dollar bridges, so a total of two billion dollars worth of bridges, and not taking into account all of the other parts of the infrastructure equation that are in Interbay, such as rail, bikes, pedestrians, transit.

There are some very cute accessory things that go along with those two billion dollar bridges that they call pedestrian infrastructure. But really, it is bending pedestrian infrastructure and transit infrastructure to the service of these giant highways running through the city.

Mark: Yeah, it's really clear that the highway is the main part of what they're trying to build there. Anytime you look at pedestrian infrastructure or bike infrastructure, it always just winds around the car stuff like a pretzel.

Laura: So I think your readers should understand who's in control here. The people that are in control are the BNSF [railroad], the Ports, the maritime industry and the freight industry. They have the power in this region. So it's not a normal conversation about, like, the Roosevelt protected bike lane. We are dealing with forces way different than a Roosevelt protected bike lane situation. You're dealing with national freight companies, national railway, ports. Ports have so much power, so much power to shape this.

And so all those forces are so big in comparison with just a little ant walking over the Emerson interchange or a little ant walking over Dravus [Street] or a little bike rider crossing the Ballard bridge and having to do this weavy-ass stupid thing to get to the other side. Like we are so minimized in the economic forces, the capitalist forces, not to make this about capitalism, but this is about the ports and the maritime industry and the freight industry wanting not one thing that will slow their economic engines.

Mark: Yeah, I mean, not just that, but the military as well. They were mandated to be major stakeholders in this entire process. So it's kind of the capitalist military industrial complex. And we're just trying to cross the bridge, you know, to get to a brewery. And I think that we're way the heck down the list of priorities.

Laura: The little chicken is trying to cross the road.

Ray: Mark, were you the one that threw out the line that these are just scraps of transit infrastructure in exchange for big highways?

Mark: Yeah, that's exactly what it looks like to me. I mean, no one has given thought to how a person riding a bike gets from where they are to where they want to be and back again. It's all just wound around all of the car infrastructure.

Laura: A little birdie told me that they suggested a signal so that folks on bikes could cross at 15th [and Emerson]. And that certainly did not end up anywhere.

Mark: Yeah, you can see that in the Ballard Bridge study. Marni Heffron with Heffron Transportation, they consider an at-grade intersection there. But because of her projections or the traffic volumes that she says is going to be moving through there, there really isn't, because of those projections for high vehicle traffic...she says it's an intersection that would simply not be workable. And so she defaults back to the SPUI [single point urban interchange]...

Laura: Death spiral. Highway spaghetti or death spiral?

Ray: We could go with spaghetti incident" or death spiral".

Mark: Yeah, so they default to that because according to her projections, that's the only way to get all those vehicles, cars and trucks and everything else through that corridor.

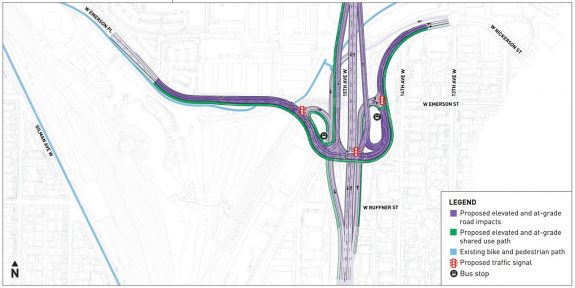

This SPUI interchange is the only proposed design for Emerson and 15th Ave W moving forward in the Ballard Bridge replacement study.

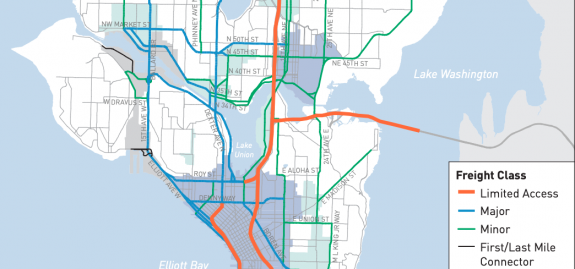

Ray: One of the points that goes to is how the north end of Interbay connects to the network of highways in the area. If you look at the way that the truck freight plan for the city is set up, it's that there is a loop that comes off I-5 goes through Interbay and comes back to Interstate 5. And it just ensures that the city is hell bent on keeping a north exit from Interbay going through Ballard and northward to reattach to I-5.

Seattle's freight master plan for the area encompassing Ballard and Interbay.

Laura: Ray, can you say that in seven words? That's too many words.

SBB: The freight plan is the highway plan.

Ray: The freight plan is the highway plan for the 1950s without bulldozing Laurelhurst.

SBB: And the traffic projections, are they reasonable?

Ray: They're 100 percent broken. They are 20 percent higher than anything that has ever been seen on the Ballard bridge, and they don't take into account any sort of mitigation or reduction in traffic.

Mark: Yeah, the interesting thing is, you look at the traffic projections in SDOT's own traffic reports and you look at the trends for vehicle miles traveled and they're pretty steady going all the way back as far as we measure, even though population is increasing, the number of homes is increasing, number of jobs is increasing. Traffic stays the same. And for the traffic engineers, the Marni Heffrons of the world, that makes no sense because their models are telling them that any time you add a person, you're going to have a person in a car. But in reality, when people live in denser communities, they can walk more, they can bike more...If you build that infrastructure.

But what people like her are doing is really, you know, they're causing this infrastructure to be built and they're creating the traffic, they're projecting it, and then they're creating it by mandating that this car infrastructure has to be built. It's a self-fulfilling prophecy. It's induced demand.

Ray: I would throw in there that Heffron [Transportation] has 20 years of this. That organization wrote the BINMIC [Ballard Interbay Northend Manufacturing Industrial Center] traffic study. (Editor's note: This study dates to 1998 and is a precursor to BIRT) And is now back again to put in this SPUI, the spaghetti incident, death spiral.

Laura: So let's talk about people with disabilities. I have chronic pain and several overlapping health conditions, that means that sometimes when I take the D Line- in the before times when I was taking the D Line every day- going up and over Emerson to get to my place was so painful. And I don't know if the future plans for that interchange mean that there will be an elevator that would take people that have strollers or people that are in wheelchairs, up the stairs and over... Or if the expectation continues to be that if you're in a wheelchair, if you have some other issue where stairs are hard for whatever reason, that you're supposed to go up to Dravus and then come back down. Because a lot of days I was when I wasn't having a good day, that's what I would do, is I would go an extra stop to Dravus and then walk over the Dravus overpass and up a hill and then down to my house instead of crossing at Emerson because the crossing underneath, if it was dark, I definitely wouldn't go underneath there. Honestly, there's no way.

And even going up and over the stairs, it was so dark I had to carry a flashlight to see the stairs. So just like the actual experience of someone that lives right there...you get off the bus and you're just like...There were times that I ran across 15th at night. People run across 15th. I can see out my window people, people cross all day long south of the Ballard Bridge and I tweeted about that and other people chimed in about what part of 15th they were on and what jaywalking they did and how they almost died. And anybody that lives up and down that spine, whether it's on the Ballard side or the Interbay side, knows that the jaywalking temptation is so high. And I feel like that's where pedestrian deaths happen, when you make that gamble and you're like, you know what, I'm just going to run across because I don't want to go up and over right now.

Mark: We know for a fact that people with disabilities were a total afterthought...I was on a call with the BIRT team and Ballard greenways and we brought up people with disabilities and what have they been considering them? And that was the first moment when they did think about it. We said you really need to get in contact with orgs who can inform you about these issues. And I don't know if they did or not. I'm not 100 percent sure who else they reached out to. But it was in that meeting that was the first moment that they considered it. And really that should have been considered at the very beginning.

SBB: So what can we do to change things?

Laura: Ray and I had a meeting with a legislator and and it's clear that in 10 or 15 years when we're actually making the nitty gritty decisions it's going to be really important to have elected champions that can push back against these really powerful interests because the electeds that are there now they really care about tourism dollars and economic dollars. Jenny Durkan's industrial lands plan's north star was workforce jobs and preserving industrial lands jobs. And they're putting in a brand new school at the fisherman's terminal. And they're doing all of this work around maritime industry jobs. But...There won't be a maritime industry if we have massive global warming.

Ray: Their words very much say industrial jobs, but their actions and their zoning and their infrastructure investments all say continue putting money into cars and big box stores and mini storage units and let people speed through our industrial lands and lay them to waste at the foot of a giant parking lot in front of a grocery store.

Laura: And breweries!

Ray: Psst! The breweries are good!

Laura: No, no, I think we should talk about that. So if the future of this community is distilleries and breweries...So you've got Rooftop Brewing. You've got a distillery down the street from me across the way on the Fisherman's Terminal side you've got at least two or three breweries...and so if this is going to be a family friendly outdoor eating food truck...If that's part of the future of our industrial lands? Boy, are we making decisions about the fact that you're going to have to drive to get drunk

Ray: To your larger question, the immediate questions of what we need to do is that we need to shelve the BIRT. Period. There is already inertia from the BIRT study for people to kind of pick things out of it and turn to this new administration, the new Biden administration to say here's a couple of things that are shovel ready. And nothing in that study is shovel ready. We need to be on the ball and say BIRT is dead. Let it gather dust. The second thing is we need to go to the legislature this year and we need to support a stronger growth management act. You know, the bill numbers right now, it's house bill 1220 for housing. It is 1099 for climate change. (Editor's note: getting a hearing today in the legislature) And then it is an upcoming one for racial equity.

We need a better growth management act in order to have a strong, comprehensive plan for the city in 2024. It's going to be that comprehensive plan in 2024 that throws out twenty five years of piss poor planning in this region and really supports strong infrastructure and racial equity and the type of housing and industrial plans that we need in this area.

Mark: I think if I had to single out like a couple elements of the BIRT, that can really make a pivotal difference on how the entire corridor works for people...It's the Ballard Bridge, whether it's high, medium or low. And it's 15th, whether we actually have a complete street on 15th and Eliott. That makes a huge, huge difference. If we have anything but a low bridge, you know, if we end up getting a ton of Biden money, that could actually make it worse because we'll end up with a medium or high bridge. And we talk about breweries, a medium or high bridge means an off-ramp right in front of Reuben's Brews deep in Ballard. The higher you raise it, the farther out it goes and the bigger it gets and the more flyovers you end up with and the harder it is for people to walk, bike and roll across that bridge. So the high, medium or low issue is big. And if it's low, we have a chance to salvage the situation.

Elliott Ave W south of 15th Ave W in Interbay.

15th and Eliott, that's an awful street, and if we can actually have a complete street with walking, biking, transit access and yes, you can have a lane for cars and trucks. But if we can actually use our Complete Streets Ordinance on that street, that makes a big difference for people trying to cross it.

Ray: So the question for the Ballard Bridge is, what is that bridge supposed to be carrying, freight-wise, except local stuff to Ballard and Crown Hill or trying to loop back to I-5. And I-5 traffic shouldn't be starting in Ballard to get back to the highway...It over builds the entire system. So to Mark's point, does a higher Ballard bridge with less openings necessarily induce freight on that road? And I think if we make 15th Avenue a much safer road, put it, on a strict road diet, we end up answering some of that question by saying, no, this is a local street.

Laura: But if we're going to build a bunch of new affordable housing in Interbay and we're going to have twenty five acres of affordable housing at the armory, for example, or something like that, then we need to be thinking in the long run about extracting community benefit for future residents that aren't there yet. That could be a different demographic than exists in the region right now.

Ray: But on top of that...They are doing a very poor type of community benefit, and it is the one that Magnolia and Queen Anne and Ballard have loudly said they want. And that is a faster drive downtown. That is the one community benefit that BIRT has found, and that they have hit over and over again. They polluted the entire argument by throwing out this number of not replacing the Magnolia bridge one to one, which would add 13 minutes to the traffic to a commute from Magnolia. And that number has polluted every debate about this issue, because if we buy that argument, if we don't replace the Magnolia Bridge, one to one, somebody in Magnolia has 13 more minutes of sitting in their car.

The current Magnolia Bridge.

Mark: Can I just add you know when we say 15 minute neighborhoods, we're talking about 15 minutes to walk or bike. We're not talking 15 minutes to drive. It's not part of the definition. And so a bridge that you can cross, or 15th Avenue or Eliott that you can cross, brings Queen Anne and Interbay and Magnolia and Ballard closer together and more things all of a sudden will be within that 15 minute bike and walk shed. And there are tremendous benefits that happen when we can bring these neighborhoods together and bring them closer in time- obviously we can't do it geographically. But if we can bring those neighborhoods closer together in time, I think that should actually be the goal of this study, not to move cars faster, to bring us closer. And right now, that's not part of it.

-

You can read more about the BIRT in The Urbanist or at the City's project page.