Before the Kraken, there was Seattle's 1st Stanley Cup winner

When the Seattle Kraken reveal their No. 1 goalie in Wednesday's NHL expansion draft, some people will inevitably compare that player to Marc-Andre Fleury. Maybe this won't be fair. Stanley Cup rings graced three of Fleury's fingers when the Vegas Golden Knights snared him from the defending champion Pittsburgh Penguins in 2017. Fleury just won the Vezina Trophy and has led the league's 31st club on multiple playoff runs.

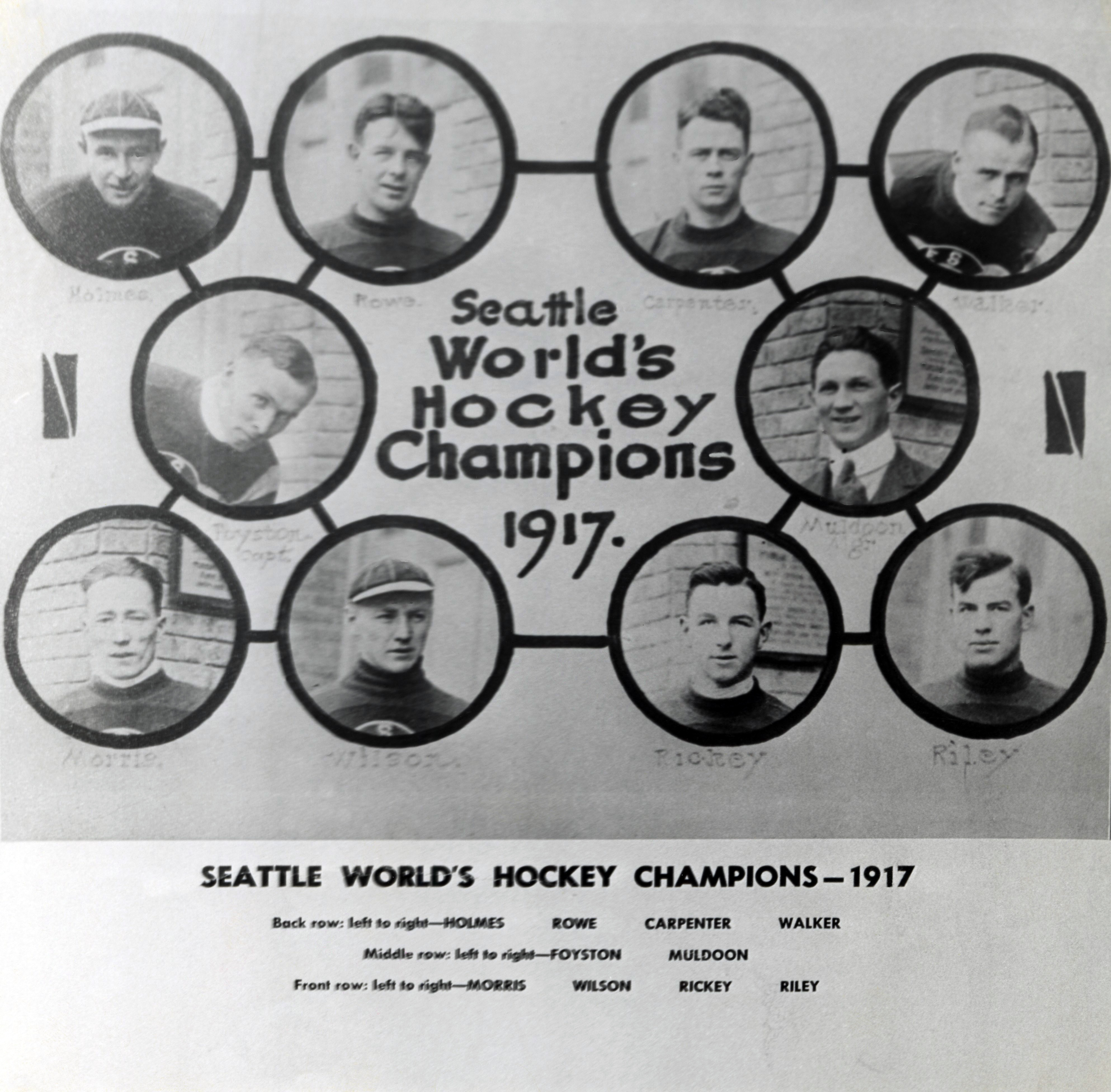

Pacific Northwest history buffs will have another reference point in mind: Hap Holmes, who manned the crease for the 1916-17 Seattle Metropolitans, the Stanley Cup's first American champion. That momentous season, Holmes was 29 years old and bald. The ball cap he wore in net guarded him from the tobacco that road fans spat at his dome. Powerless to dodge the juice, Holmes was agile and heady with the puck in front of him. Hap was short for Happy, and in life and in victory, a smile was his default expression.

"Where some goalers are spectacular, he was scientific," the Hall of Fame player Cyclone Taylor, long an opponent of Holmes in the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, once said about him. "We always regarded him as a stone wall."

Bruce Bennett / Getty Images

Bruce Bennett / Getty Images Holmes' netminding powered Seattle to glory the season before the NHL formed. In the Stanley Cup's earliest years, amateur clubs from Montreal, Ottawa, and Winnipeg hoarded possession of the trophy, fending off challengers that hailed from Rat Portage, Ontario, to Dawson City, Yukon. From 1893-1915, no American team played for the Cup, but in 1916, the Portland Rosebuds fell one goal short of denying the Montreal Canadiens their first title.

The Canadiens played in the National Hockey Association back then and Portland and Seattle were PCHA foes, battling the Vancouver Millionaires for supremacy of the pro loop that introduced the goal crease, blue line, and forward pass. The Metropolitans debuted in the league in 1915-16 as a ready-made contender, not unlike Vegas a century later. Some of the era's most fearsome scorers and all-around players returned to Seattle the next fall, nine men poached from across Canada to form what endures as the city's best roster.

Three stalwart Metropolitans - Holmes, Jack Walker, and Frank Foyston, the franchise's career goals and points leader - are in the Hall of Fame. Foyston's vision with the puck elevated his teammates. Walker mastered the hook check, whereby he'd backcheck and sink to a knee to dispossess opponents. Imitators spiraled out of position if the move failed, but "Walker never missed," author Kevin Ticen wrote in "When It Mattered Most," his definitive account of Seattle's championship season.

The 1916-17 Mets were coached by Pete Muldoon, 29, a regional light heavyweight boxing champ who preached speed and team play on the ice. Muldoon's club could irritate (winger Cully Wilson "played on the edge of rage," Ticen wrote) and dominate (Foyston and Bernie Morris combined to pot 73 goals in 24 games). Helpfully, Holmes was a star, too. He allowed 80 goals that regular season, or 3.33 per night - elite considering that defensemen often played the entire 60-minute game.

Operating out of the $100,000 Seattle Ice Arena - the Metropolitan Building Company constructed the barn in 1915 and inspired the squad's name - the Mets went 16-8 against the Millionaires, Rosebuds, and Spokane Canaries. 1916-17 was a lost season for the Canaries, who moved south from Victoria when Canadian authorities commandeered their home rink for war training. Seattle routed Spokane for seven wins, including 14-1 and 7-0 scores to start and end February.

When a dirty slash bruised his knee in the 14-1 affair, Morris ignored team medical advice to return the next game. By March 2 at Portland, the last day of the season, he was limber enough to score twice and clinch Seattle the PCHA title. Second-place Vancouver iced its own Hall of Fame trio - Taylor, Gordon Roberts, and PCHA co-founder Frank Patrick - but ran out of time to erase a narrow standings deficit and reach the Stanley Cup Final.

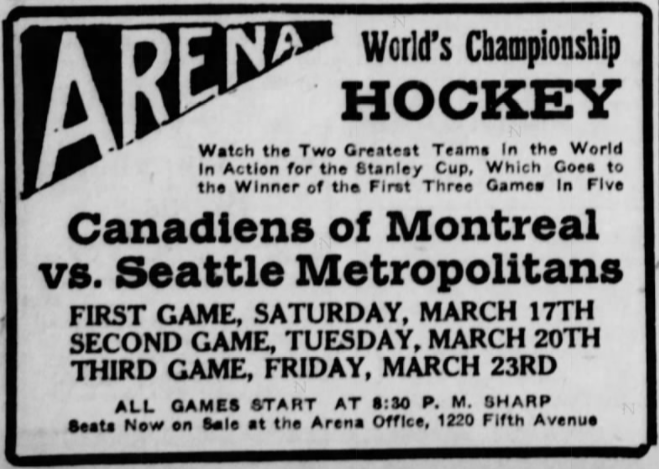

There, the Mets got to face the NHA champion Canadiens, who edged the original Ottawa Senators 7-6 in that league's two-leg final. Tied on aggregate goals late in Game 2, Montreal capitalized on an Ottawa goaltending blunder to book passage to Seattle, where the whole best-of-five Stanley Cup clash was to be held. The reigning Cup winners boarded a private train that same night, leaving the trophy behind to project that they'd retain ownership.

March 16, 1917. Seattle Star

March 16, 1917. Seattle Star Concern that the cross-continent ride would tank the Canadiens' fitness was offset by the advantages the Habs brought into the final. On average, Montreal's starters outweighed Seattle's, averaging 183 pounds each to the Mets' 156. Habs winger Didier Pitre bagged a hat trick against Portland, and four goals total, in the previous year's Cup victory. Player-coach Newsy Lalonde was hockey's greatest pre-Original Six scorer. Between the pipes was Georges Vezina, whom Fleury's award is named after.

These legends rolled toward a city that, as the Cup series neared, "could do nothing but stop, talk, and listen to hockey gossip," Seattle Star reporter Edward Hill wrote. Once a 3,500-person mill town, Seattle became a destination in the 1890s as a gateway to the Klondike Gold Rush, Ticen noted in his book. In a March 1917 Post-Intelligencer newspaper column he unearthed, sports editor Royal Brougham described the magnitude of Montreal's visit: Seattle will shake the dust of small-town sport from her feet and bust into big-league company."

Disembarking the train on Saturday, March 17, the day of Game 1, Canadiens manager George Kennedy paused to contribute to the discourse. Enlivened by Lalonde's presence on the trip - the NHA had cleared the superstar to face Seattle after he had been suspended against Ottawa for high stickwork - Kennedy predicted to reporters an easy Montreal victory. Rust from the journey might spot the Metropolitans the opener, he clarified, but the Canadiens would sweep the remaining matchups.

Georges Vezina. Bruce Bennett Collection / Getty Images

Georges Vezina. Bruce Bennett Collection / Getty ImagesAs it turned out, Kennedy was precisely wrong. Playing Game 1 under PCHA rules, with seven men on the ice per team (a rover included), Montreal shelled Holmes in an 8-4 win, netting softies that he was keen to avenge. That was the Canadiens' last triumph of the season. NHA rules governed for Game 2 the following Tuesday, but Seattle won 6-1, strengthened by Foyston's hat trick and the shutout Holmes preserved for the first 59 minutes. Irked, Lalonde butt-ended an official during a late skirmish, incurring an ejection and $25 fine.

"The poor Canadiens looked like a bunch of wooden-legged men on skates compared to the flashy speed work of the local lads," Hill opined postgame. Montreal defensemen Bert Corbeau and Harry Mummery "were at sea most of the evening," the Ottawa Journal wrote, wondering from afar if the Habs already were toast.

Game 3 confirmed they were. Down 1-0, Montreal squandered an early man advantage - Holmes lunged to knock a Corbeau one-timer wide - and resorted to playing reckless. Billy Coutu bashed Seattle's Roy Rickey twice, sparking a fight on each occasion, and Mummery was penalized 10 minutes for cross-checking Morris on the rush. Swamped by the Mets' pace, breathing heavily in the third period, the Habs conceded three goals within 1:56, permitting a hat trick from Morris this time, and lost 4-1.

Unchastened by the result, Kennedy filed a protest to have Game 3 replayed, claiming the officials erred by not allowing Mummery to serve his penalty after Coutu's elapsed. It amounted to a Hail Mary that Patrick, weighing in as PCHA president, shot down.

Happy birthday to Frank "the Blond Flash" Foyston! #ReturnToHockey

- Seattle Kraken (@SeattleKraken) February 2, 2019

Foyston played 9 seasons with the Seattle Metropolitans, winning the 1917 Stanley Cup. He was elected to the @HockeyHallFame in 1958, and passed away in Seattle in 1966.

Photo & facts provided by @kticen. pic.twitter.com/7B1ydc65A0

Game 4 on March 26 was Seattle's coronation. Spurred by an opening tally that Ticen termed "vintage Mets" - Walker stole the puck, Foyston drew two defenders, Morris took his pass and juked Mummery to earn a breakaway - Seattle got up 7-0 before the bone-weary Habs managed a token response. The Ice Arena's standing-room crowd was more excited than the players: "The superiority of the Seattle team was so evident ... that it lost interest long before the final whistle blew," Spokane's Spokesman-Review newspaper wrote.

In the end, the Mets won 9-1 on six goals from Morris, upping his total for the final to 14. (This remains a Stanley Cup record.) Foyston scored seven goals in all and Holmes embodied cool underneath his protective cap, having stoned all but three shots following the Game 1 onslaught.

As for the coach, Muldoon "achieved the pinnacle of his profession" before his 30th birthday, Ticen wrote. No younger bench boss has ever won the Stanley Cup. The onus fell to Montreal to send the trophy west.

March 27, 1917. The Province

March 27, 1917. The Province The Metropolitans and Canadiens were tied in Cups when Montreal returned to Seattle for a 1919 rematch. This was the title series that influenza wrecked, confining several Habs to bed with the series tied 2-2 and killing defenseman Joe Hall four days after it was canceled. Hockey seemed insignificant, although Lalonde told reporters after Hall's funeral that Seattle would have won the decisive game.

Deprived of the opportunity, the Mets lost to Ottawa in the 1920 Cup Final, and Vancouver beat them for the PCHA title in 1921, 1922, and 1924. The Mets folded later that year when the league did, and the Ice Arena was converted into a hotel parking garage.

None of these letdowns marked the end of Holmes' hockey journey. Loaned to the NHL for the 1917-18 season, the smiley backstop led the Toronto Hockey Club - a forerunner to the Maple Leafs - to the inaugural league championship and the Cup. Reunited with Foyston and Walker on the Victoria Cougars, his name and theirs were etched on the chalice in 1925. Holmes wound up retiring with four Cup victories, the number Fleury's chasing with Vegas.

Holmes was 53 years old when he died in 1941. Thirty-one years later, he entered the Hockey Hall of Fame posthumously. In addition to Gordie Howe, his induction class included Jean Beliveau and Bernie "Boom Boom" Geoffrion, cornerstone players on many Montreal Cup teams to come.

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

Copyright (C) 2021 Score Media Ventures Inc. All rights reserved. Certain content reproduced under license.