Tiny Chips Could Lead to Giant Power Savings

Even if a GPU in a data center should only require 700 watts to run a large language model, it may realistically need 1,700 watts because of inefficiencies in how electricity reaches it. That's a problem Peng Zou and his team at startup PowerLattice say they have solved by miniaturizing and repackaging high-voltage regulators.

The company claims that its new chiplets deliver up to a 50 percent reduction in power consumption and twice performance per watt by sizing down the voltage conversion process and moving it significantly closer to processors.

Shrinking and Moving Power DeliveryTraditional systems deliver power to AI chips by converting AC power from the grid into DC power, which then gets transformed again into low-voltage (around one volt) DC, usable by the GPU. With that voltage drop, current must increase to conserve power.

This exchange happens near the processor, but the current still travels a meaningful distance in its low-voltage state. A high current traveling any distance is bad news, because the system loses power in the form of heat proportional to the current squared. The closer you get to the processor, the less distance that the high current has to travel, and thus we can reduce the power loss," says Hanh-Phuc Le, who researches power electronics at the University California, San Diego and has no connection to PowerLattice.

Given the ever-growing power consumption of AI data centers, this has almost become a show-stopping issue today," PowerLattice's Zou says.

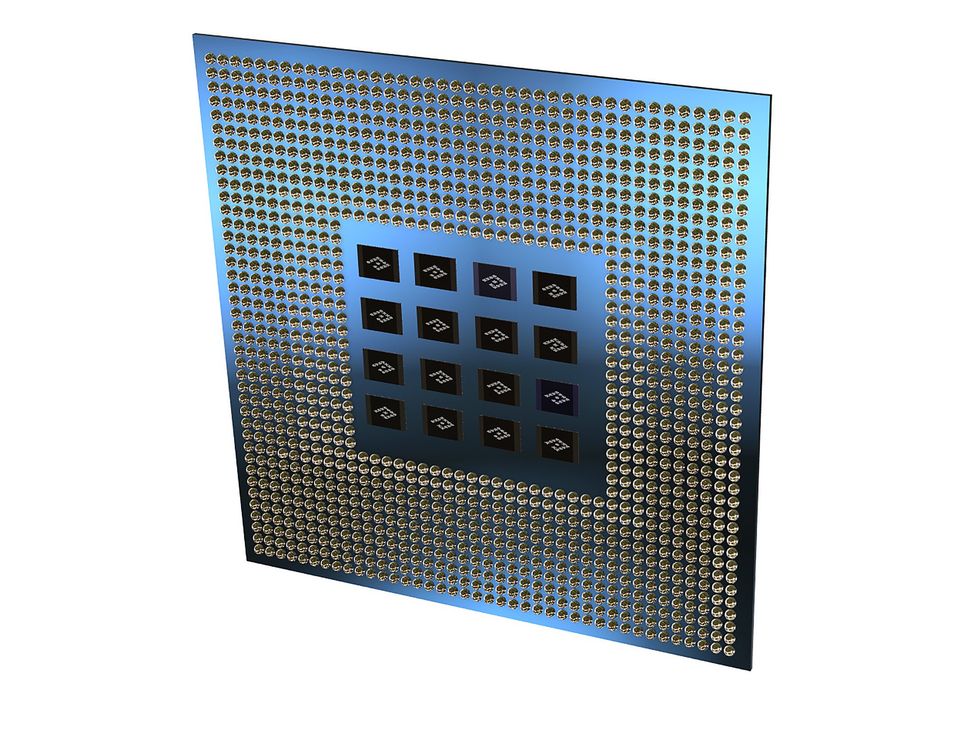

Zou thinks he and his colleagues have found a way to avoid this huge loss of power. Instead of dropping the voltage a few centimeters away from the processor, they figured out how to do it millimeters away, within the processor's package. PowerLattice designed tiny power delivery chiplets-shrinking inductors, voltage control circuits, and software-programmable logic into an IC about twice the size of a pencil eraser. The chiplets sit under the processor's package substrate, to which they're connected.

One challenge the minds at PowerLattice faced was how to make inductors smaller without altering their capabilities. Inductors temporarily store energy and then release it smoothly, helping regulators maintain steady outputs. Their physical size directly influences how much energy they can manage, so shrinking them weakens their effect.

The startup countered this issue by building their inductors from a specialized magnetic alloy that enables us to run the inductor very efficiently at high frequency," Zou says. We can operate at a hundred times higher frequency than the traditional solution." At higher operating frequencies, circuits can be designed to use an inductor with a much lower inductance, meaning the component itself can be made with less physical material. The alloy is unique because it maintains better magnetic properties than comparable materials at these high frequencies.

The resulting chiplets are less than 1/20th the area of today's voltage regulators, Zou says. And each is only 100 micrometers thick, around the thickness of a strand of hair. Being so tiny allows the chiplets to fit as close as possible to the processor, and the space savings provide valuable real estate to other components.

PowerLattice's chiplets would sit on the underside of a GPU's package to provide power from below.PowerLattice

PowerLattice's chiplets would sit on the underside of a GPU's package to provide power from below.PowerLattice

Even at their small size, the proprietary tech is highly configurable and scalable," Zou says. Customers can use multiple chiplets for a more comprehensive fix or fewer if their architecture doesn't require it. It's one key differentiator" of PowerLattice's solution to the voltage regulation problem, according to Zou.

Employing the chiplets can reduce 50 percent of power needs for an operator, effectively doubling performance, the company claims. But this number seems ambitious to Le. He says that 50 percent power savings could be achievable, but that means PowerLattice has to have direct control of the load, which includes the processor as well." The only way he sees it as realistic is if the company has the ability to manage power supply in real time depending on a processor's workload-a technique called dynamic voltage and frequency scaling-which PowerLattice does not.

Facing CompetitionRight now, PowerLattice is in the midst of reliability and validation testing before it releases its first product to customers, in about two years. But bringing the chiplets to market won't be straightforward because PowerLattice has some big-name competition. Intel, for example, is developing a Fully Integrated Voltage Regulator, a device partially devoted to solving the same problem.

Zou doesn't consider Intel competition because, in addition to the products differing in their approaches to the power delivery problem, he does not believe Intel will be providing its technology to its competitors. From a market position perspective, we are quite a bit different," Zou says.

A decade ago, PowerLattice wouldn't have room to succeed, Le says, because companies that sold processors only ensured reliability for their chips if customers purchased their power supplies as well. Qualcomm, for example, can sell their processor chip and the vast majority of their customers also have to buy their proprietary Qualcomm power supply management chip because otherwise they would say, We don't guarantee the reliable operation of the whole system.'"

Now, though, there may be hope. There's a trend of what we call chiplet implementation, so it is a heterogeneous integration," Le says. Customers are mixing and matching components from different companies to achieve better system optimization, he says.

And while notable providers like Intel and Qualcomm may continue to have the upper hand with notable customers, smaller companies-mostly startups-building processors and AI infrastructures will also be power hungry. These groups will need to look for a power supply source, and that's where PowerLattice and similar companies could come in, Le says. That's how the market is. We have a startup working with a startup doing something that actually rivals, and even competes with, some large companies."