Boise Puts “Cool Factor” ahead of Mobility

Suppose you were in charge of an Inland Northwest city of about 215,000, an island of vibrant urbanity frozen in a tax- and transit-hostile hinterland. Now suppose your city had a transit system about on a par with Wenatchee, Washington - population 35,000 - with buses running at best every 30 minutes to 10 PM on the weekday, minimal Saturday service, and exactly no service on Sundays. What kind of transit investments would you make? Well, if you're the Mayor of Boise, you look to a $111 million, "T-shaped" streetcar alignment, with a projected 2040 daily ridership of 1,400 souls.

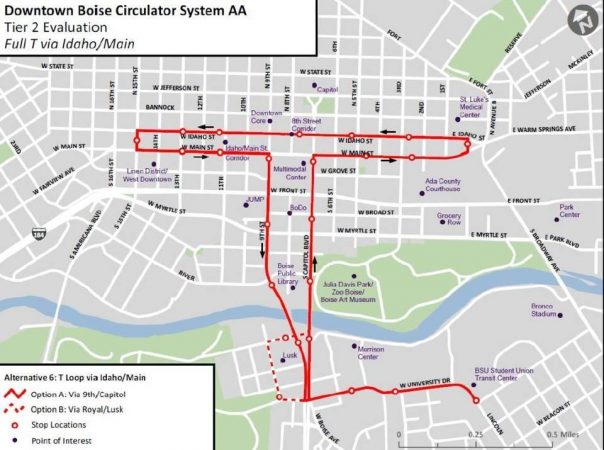

The only official information I can find from the city doesn't include minor details such as headway, transit lanes, or signal priority. One independent writer, who obtained a trove of data via disclosure request, writing in December, suggested that transit lanes are yet to be decided, and headways are likely to be 15 minutes. It's difficult to quantify distance and travel time advantage on a T- (really, J-)shaped alignment, but some eyeballing of the map suggests that the furthest-separated pair of stations are about two miles walk apart. For an able-bodied person, the circulator would be worth waiting for only between a handful of station pairs.

What makes this poignant is that Boise's same size sibling up north is a canonical example of what they should be aiming for. The Spokane Transit Authority recently passed (albeit on a second attempt) STA Moving Forward, a major package of improvements in service quality and quantity, whose banner project is a high-frequency, six-mile, $72 million battery-bus corridor, that is not at all J-shaped. Moreover, Boise appears to be trying to do the right thing with a rapid bus treatment on State Street, one of its principal suburban arterial connections, so it's clear that someone there actually knows what effective medium-size city transit service looks like.

If Boise actually builds this park-and-trundle service, they are liable to find what every other "placemaking" streetcar has found: dispite cherry-picking only the densest, most-walkable parts of the urban area, these services have a very low ceiling. In February, Portland's much-vaunted streetcar system bragged of serving a record 16,300 daily riders. This might sound impressive, until you realize that the rest of the transit system moved 317,000 people per weekday in same month, with MAX light rail and boring, uncool bus service doing the heavy lifting at 123,400 and 188,300 riders respectively. Of those 16,300 rides, a considerable fraction are surely cannibalized from walking, bikeshare, or transit service on adjacent streets, rendering them at best a wash if you care about cost effectiveness, energy consumption, or the quality of the downtown urban experience.

With the benefit of 15 years' hindsight, perhaps we can generalize a little and say that cannibalization has been the theme of the American mixed-traffic streetcar "revival". Every mayor, every body politic, has a finite amount of attention to devote to the issues of the day. Time and effort spent building slow streetcars is spent solving a non-problem, while real problems fester. Most local dollars that could be raised for a streetcar could be raised for other, more effective uses in the common good; meanwhile, the federal transit funding outlook is grim. Perhaps we can take this as an opportunity to refocus on things that actually work.