Do we have evidence for an exomoon? Ask again in a year.

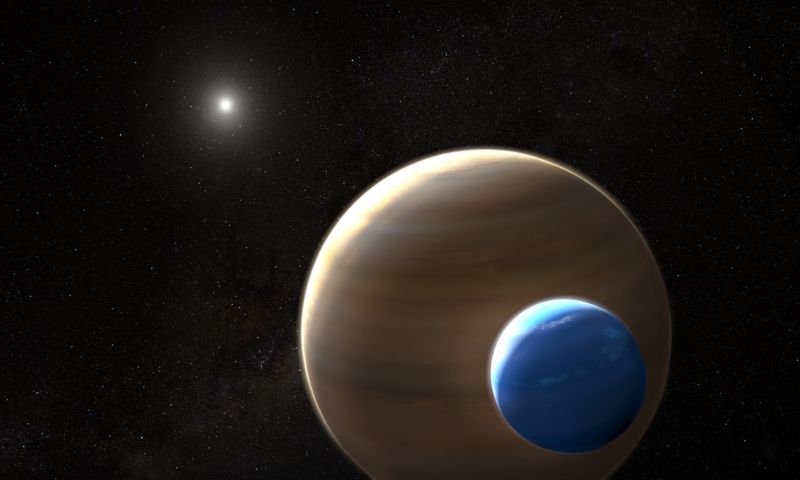

Enlarge / An artist's impression of what the massive system would look like. (credit: NASA/ESA)

At this point, we've spotted thousands of planets orbiting other stars. But we still don't have a good picture of whether exosolar systems are similar to our own Solar System. Things like asteroids and comets are far too small to resolve given our current technologies. But there is a chance we could detect the presence of a major feature of our Solar System elsewhere: exomoons. There are ways we could currently detect them, but orbital dynamics makes doing so fairly unlikely.

But a group of researchers have suggested there may be an exomoon orbiting a planet discovered by the Kepler mission, and the researchers' data was compelling enough to get them time on the Hubble Space Telescope. But the additional data both makes the case for the moon better and worse (don't worry, we will explain that). And the model that fits the data best involves a Neptune-sized moon orbiting a super-Jupiter.

Timing is everythingThere are two ways to potentially identify an exomoon. The first involves the amount of light blocked while the exoplanet orbits its host star. When the moon isn't eclipsing or being eclipsed by its planet, it should block a small bit of additional light during the transit. Look at enough transits, and there could be a regular pattern of additional light blocked. But this method relies on the moon being large enough to block a significant amount of light, which is something that's far from guaranteed.

Read 11 remaining paragraphs | Comments