Lessons from scorching hot weirdo-planets

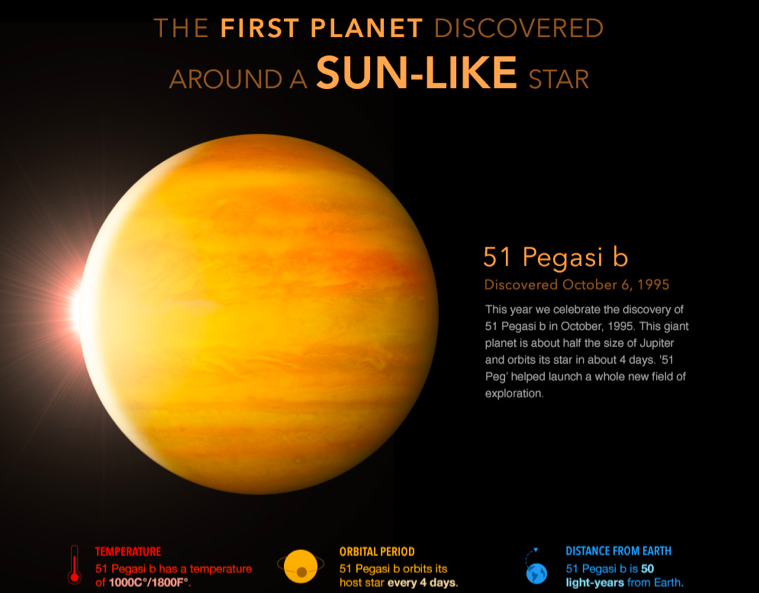

Enlarge / 1800 degrees Fahrenheit? That is a hot Jupiter, eh? (credit: NASA)

In 1995, after years of effort, astronomers made an announcement: They'd found the first planet circling a sun-like star outside our solar system. But that planet, 51 Pegasi b, was in a quite unexpected place-it appeared to be just around 4.8 million miles away from its home star and able to dash around the star in just over four Earth-days. Our innermost planet, Mercury, by comparison, is 28.6 million miles away from the sun at its closest approach and orbits it every 88 days.

What's more, 51 Pegasi b was big-half the mass of Jupiter, which, like its fellow gas giant Saturn, orbits far out in our solar system. For their efforts in discovering the planet, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz were awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize for Physics alongside James Peebles, a cosmologist. The Nobel committee cited their "contributions to our understanding of the evolution of the universe and Earth's place in the cosmos."

The phrase "hot Jupiter" came into parlance to describe planets like 51 Pegasi b as more and more were discovered in the 1990s. Now, more than two decades later, we know a total of 4,000-plus exoplanets, with many more to come, from a trove of planet-seeking telescopes in space and on the ground: the now-defunct Kepler; and current ones such as TESS, Gaia, WASP, KELT and more. Only a few more than 400 meet the rough definition of a hot Jupiter-a planet with a 10-day-or-less orbit and a mass 25 percent or greater than that of our own Jupiter. While these close-in, hefty worlds represent about 10 percent of the exoplanets thus far detected, it's thought they account for just 1 percent of all planets.

Read 39 remaining paragraphs | Comments