Images obtained of two stars in the process of a merger

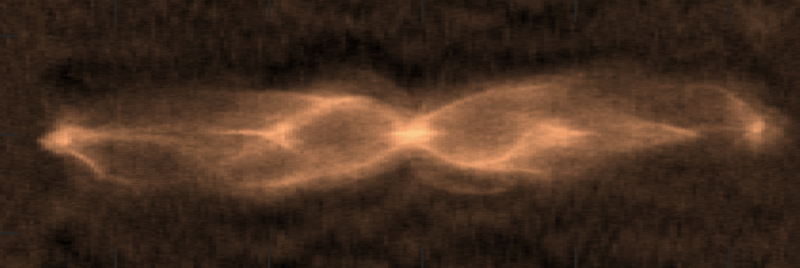

Enlarge / Some of the structures present in the area around the recently described star system.

We know two facts about our galaxy that are, in isolation, mundane. One is that many stars are part of a two-star system and may orbit each other at distances similar to those of the planets in our own Solar System. The second is that stars that are similar in mass to the Sun will end their fusion-driven existences by expanding into bloated red giants. Put those two facts together and you have an inescapable and intriguing consequence: a lot of stars are going to end up expanding enough to swallow their neighbor.

What happens then can be hard to understand, in part because there are so many potential options. If the companion star is massive enough, the transfer of mass could trigger its explosion. It's also possible that friction could bleed energy from the orbit of the companion star, reducing its orbit until it is merged. Or, because the outer layers of the red giant are so diffuse, it's possible that the cores of the two stars could end up sharing a single envelope, continuing to orbit each other.

While it's easy to know when we've observed an explosion, it's much harder to figure out when we're looking at either of the latter two options. Normally, we'd rely on physical models to tell us what would happen in these cases, but generating a model of these conditions has turned out to be pretty complex. Now, however, some researchers are suggesting that a common-envelope binary star is the best way of explaining an object they've imaged.

Read 12 remaining paragraphs | Comments