X-rays reveal the key to preserving Edvard Munch’s The Scream

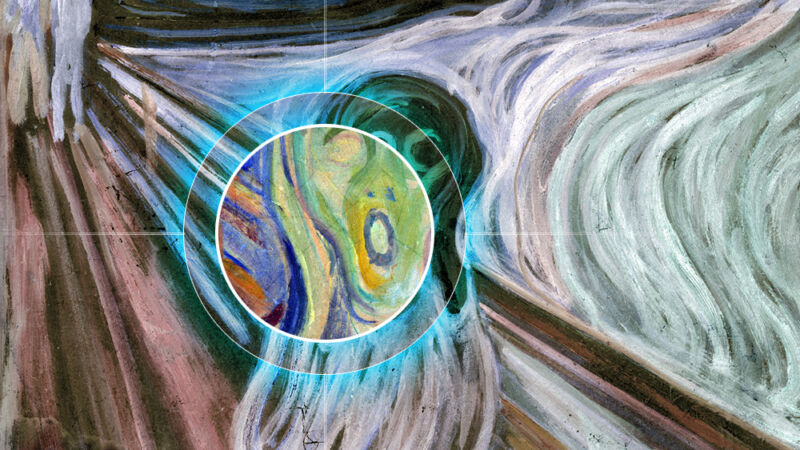

Enlarge / Edvard Munch's 1910 version of The Scream shows signs of degradation. New synchrotron radiation analysis provides a key to its preservation. (credit: Edvard Munch / Aurich Lawson)

Edvard Munch's The Scream is one of the most iconic paintings of the modern era, inspiring silkscreen prints by Andy Warhol, the killer's mask in the 1996 film Scream, and the appearance of an alien race known as The Silence in Doctor Who, among other pop culture tributes. But the canvas is showing alarming signs of degradation. That damage is not the result of exposure to light, but humidity-specifically, from the breath of museum visitors, perhaps as they lean in to take a closer look at the master's brushstrokes. That's the conclusion of a new study in the journal Science Advances by an international team of scientists hailing from Belgium, Italy, the US, and Brazil.

There are actually several versions of The Scream, each unique: two paintings-one painted in 1893, and another version painted around 1910-plus two pastels, a number of lithographic prints, and a handful of drawings and sketches. The inspiration for the painting was a particularly spectacular sunset that the artist witnessed while out for a walk. Munch noted the incident in a January 22, 1892 diary entry:

One evening I was walking along a path, the city was on one side and the fjord below. I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fjord-the sun was setting, and the clouds turning blood red. I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The color shrieked. This became The Scream.

Some astronomers believe this sunset was likely an after-effect of the 1883 eruption of Mount Krakatoa in Indonesia; reports of similarly intense sunsets were made in several parts of the Western Hemisphere during several months in 1883 and 1884. Other scholars dismiss this notion, arguing that Munch was not known for painting literal renderings of things he had seen. An alternative explanation is that the red skies were the result of nacreous clouds common to that particular latitude. But the spot where Munch most likely witnessed the sunset has been identified: a road overlooking Oslo from the hill of Ekeberg.

Read 12 remaining paragraphs | Comments