New African genomes: Complicated migrations and strong selection

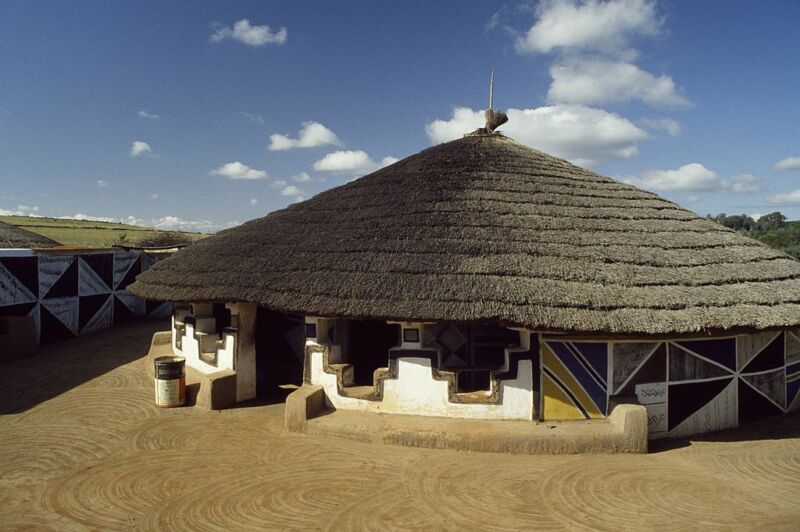

Enlarge / A building in a Ndebele village, South Africa. The Ndebele-language speakers, currently about a million strong, arrived in South Africa with the Bantu expansion. (credit: DEA / S. VANNINI / Getty Images)

Humanity originated in Africa, and it remained there for tens of thousands of years. To understand our shared genetic history, it's inevitable that we have to look to Africa. Unlike elsewhere on the planet, however, African populations were present throughout our history-they weren't subject to the same sorts of founder effects seen as populations expanded into unoccupied areas. Instead, those populations were scrambled as groups migrated to new areas within the continent.

Sorting out all of this would be a challenge, but it's one that has been made harder by the fact that most genome data comes from people in the industrialized world, leaving the vast populations of Africa poorly sampled. That's starting to change, and a new paper reports on the efforts of a group that has just analyzed over 400 African genomes, many coming from populations that have never participated in genome studies before.

New diversityNew genetic variants arise all the time. As a result, the oldest populations-those in Africa-should have the most novel variations. But identifying these populations can be hard when there are so many; the study mentions that there are over 2,000 ethnolinguistic groups in sub-Saharan Africa, and only a small number of those have been sampled. The new study is a huge step forward, with over 400 complete genome sequences from geographically dispersed populations. But even there, it's limited, adding only 50 new ethnolinguistic groups and two vast regions of the continent represented by people from a single country (Zambia for Central Africa and Botswana for Southern Africa).

Read 16 remaining paragraphs | Comments