Experts debate the risks of made-to-order DNA

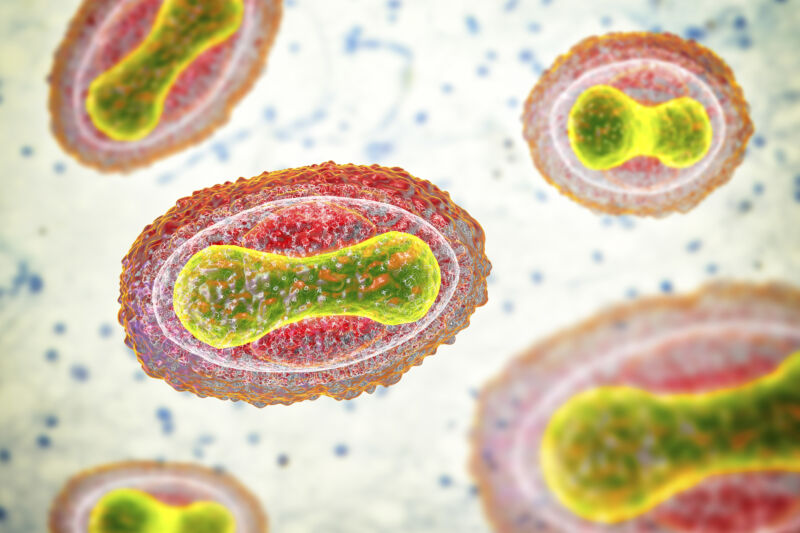

Enlarge / Illustration of a smallpox (variola) virus. A membrane (transparent) derived from its host cell covers the virus particle. Inside this lies the core (green), which contains the particle's DNA genetic material. The core has a biconcave shape. (credit: Katerya Kon / Science Photo Library via Getty)

In November 2016, virologist David Evans traveled to Geneva for a meeting of a World Health Organization committee on smallpox research. The deadly virus had been declared eradicated 36 years earlier; the only known live samples of smallpox were in the custody of the United States and Russian governments.

Evans, though, had a striking announcement: Months before the meeting, he and a colleague had created a close relative of smallpox virus, effectively from scratch, at their laboratory in Canada. In a subsequent report, the WHO wrote that the team's method did not require exceptional biochemical knowledge or skills, significant funds, or significant time."

Evans disagrees with that characterization: The process takes a tremendous amount of technical skill," he told Undark. But certain technologies did make the experiment easier. In particular, Evans and his colleague were able to simply order long stretches of the virus's DNA in the mail, from GeneArt, a subsidiary of Thermo Fisher Scientific.