X-rays reveal hidden “first drafts” of ancient Egyptian paintings at Theban Necropolis

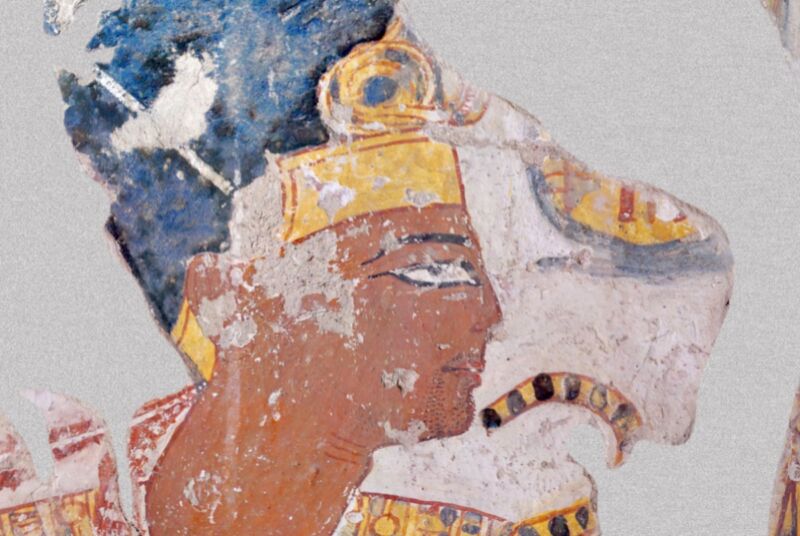

Enlarge / Portrait of Ramesses II in Nakhtamun tomb, Chief of the Altar in the Ramesseum (possibly 20th Dynasty, circa 1100 BCE). (credit: Martinez et al./CC-BY 4.0)

Researchers have discovered evidence of earlier versions of two ancient Egyptian paintings located in tomb chapels in the Theban Necropolis, according to a new paper published in the journal PLoS ONE. In one, there is a ghostly third hand partially hidden under a white overprinted layer; the other has adjustments to the crown and other royal items in a portrait of Ramesses II. These discoveries were made with a portable macro-X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) imaging device that enabled the researchers to analyze the paintings on site, with no need for taking physical samples.

X-rays are a well-established tool to help analyze and restore valuable paintings because the rays' higher frequency means they pass right through paintings without harming them. X-ray imaging can reveal anything that has been painted over a canvas or where the artist may have altered his (or her) original vision. For instance, Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Windowwas first subjected to X-ray analysis in 1979 and revealed the image of a Cupid lurking under the overpainting. In 2020, a team of Dutch and French scientists used high-energy X-rays to unlock Rembrandt's secret recipe for his famous impasto technique, believed to be lost to history.

In 2021, scientists used macro-X-ray fluorescence imaging to map out the distribution of elements in the paint pigments of Jean-Louis David's famous portrait of 17th-century chemist Antoine Lavoisier and his wife Marie-Anne-including the paint used below the surface-to create detailed elemental maps for further study. Earlier this year, scientists used X-ray powder diffraction mapping and synchrotron micro X-ray analysis to study Rembrandt van Rijn's 1642 masterpiece The Night Watch, and found rare traces of a compound called lead formate.