New genetic analysis of Ötzi the Iceman yields some surprising findings

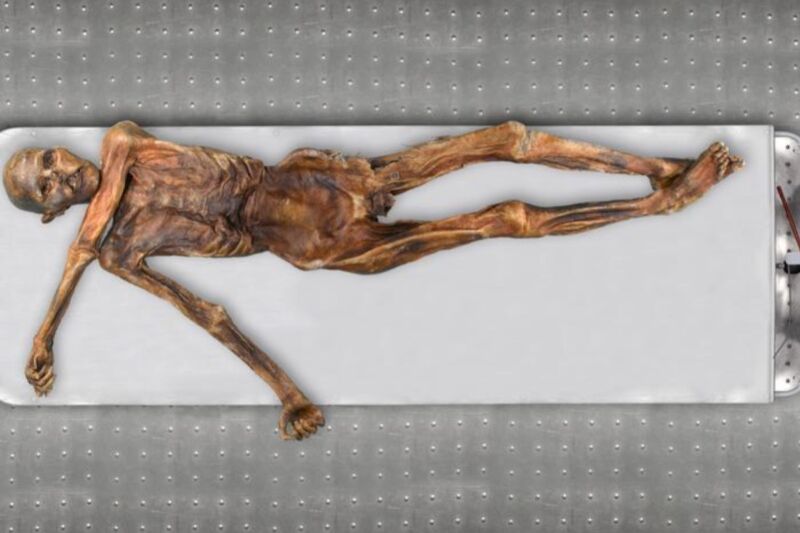

Enlarge / Study reveals that compared to other contemporary Europeans, Otzi's genome had an unusually high proportion of genes in common with those of early farmers from Anatolia. He was also likely bald (or nearly so) when he died. (credit: South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology/Eurac/Marco Samadelli-Gregor Staschitz)

In 1991, a group of hikers found the mummified remains of Otzi the Iceman emerging from a melting glacier in the Alps-likely murdered, judging by the remains of an arrowhead lodged in his shoulder. The mummy's genome was first sequenced in 2012, whereby the world learned that he likely had brown eyes, type O blood, blocked arteries, Lyme disease, and lactose intolerance. That first genetic analysis also determined that Otzi was descended from Steppe Herders hailing from Eastern Europe who migrated to the region some 4,900 years ago.

However, according to a recent paper published in the journal Cell Genomics, Otzi actually has more common ancestry with early farmers who migrated from Anatolia roughly 8,000 years ago, and the earlier findings were the result of modern DNA contaminating the original sample. The authors also used the latest advanced sequencing technology to paint a more accurate picture of the Iceman's appearance and other genetic traits. Most notably, his skin was probably much darker than previously assumed, and he was likely bald, or nearly so, when he died.

As previously reported, archaeologists have spent the last 30 years studying the wealth of information about Copper Age life that Otzi brought with him into the present. Studies have examined his genome, skeleton, last meals, tattoos, and the microbes that lived in his gut. For instance, in 2016, scientists usedDNA sequencing to identify how Otzi's clothing was made and found that most of it was made from domesticated cattle, goats, and sheep, although his hat was made from brown bear hide and his quiver from a wild roe deer.