Colorful quantum dots snag 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

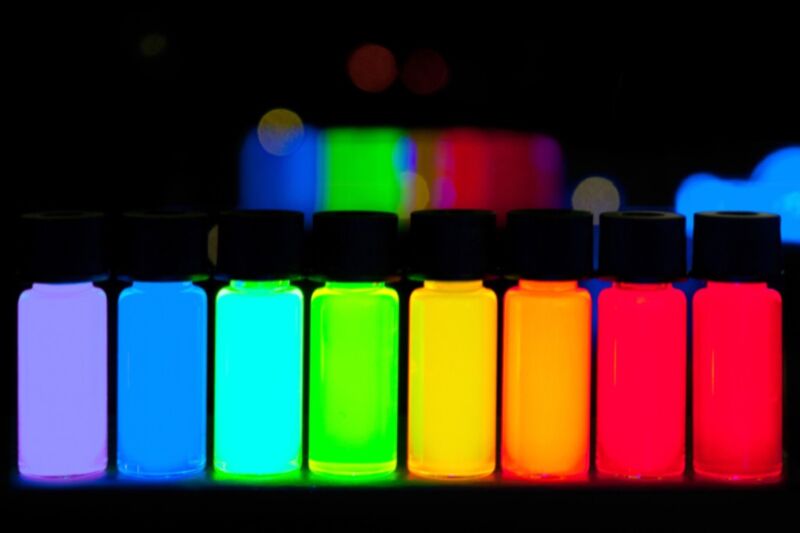

Enlarge / Vials of quantum dots with gradually stepping emission from violet to deep red. (credit: Antipoff/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Once thought impossible to make, quantum dots have become a common component in computer monitors, TV screens, and LED lamps, among other uses. Three of the scientists who pioneered these colorful nanocrystals-Moungi G. Bawendi, Louis E. Brus, and Alexei I. Ekimov-have been awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for the discovery and synthesis of quantum dots." The news had already leaked in the Swedish news media-a rare occurrence-when Johan Aqvist, chair of the Academy's Nobel committee for chemistry, made the official announcement, complete with five flasks containing quantum dots of many colors lined up before him as a visual aid.

A quantum dot is a small semiconducting bead a few tens of atoms in diameter. Billions could fit on the head of a pin, and the smaller you can make them, the better. At those small scales, quantum effects kick in and give the dots superior electrical and optical properties. They glow brightly when zapped with light, and the color of that light is determined by the size of the quantum dots. Bigger dots emit redder light; smaller dots emit bluer light. So, you can tailor quantum dots to specific frequencies of light just by changing their size.

Physicists had thought since the 1930s that particles at the nanoscale would behave differently. That's because, according to quantum mechanics, there is much less space for electrons when particles are that small, squeezing electrons together so tightly that material properties can change dramatically. Scientists succeeded in making nanoscale-thin films on top of bulk materials in the 1970s that had size-dependent optical properties, in keeping with those earlier predictions. But making those films required ultra-high vacuum conditions and temperatures near absolute zero, so nobody expected them to have much practical use.