Deep into the Kuiper Belt, New Horizons is still doing science

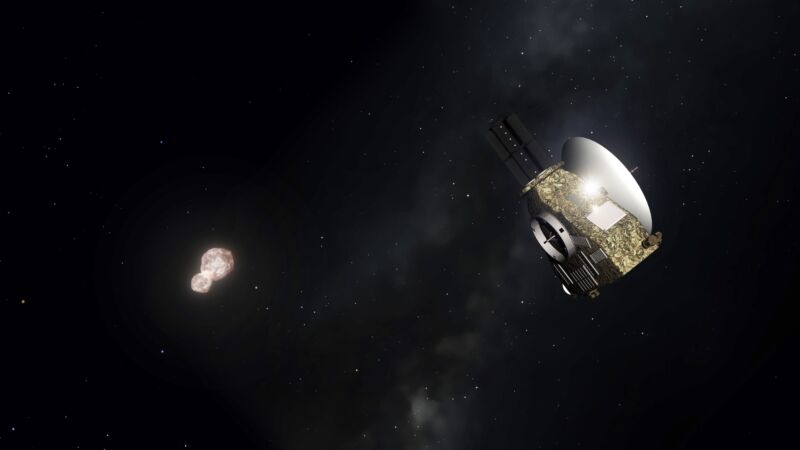

Enlarge / Artist's impression of the New Horizons spacecraft at Arrokoth. This astronomical body is the most distant object visited by human spacecraft, with the flyby of NASA's New Horizons spacecraft taking place on January 1, 2019.

New Horizons is now nearly twice as far from the Sun as Pluto, the outer planets are receding fast, and interstellar space is illuminated by the vast swath of the Milky Way ahead. But the spacecraft's research is far from over. Its instruments are all functioning and responsive, and the New Horizons team has been working hard, pushing the spacecraft's capabilities to carry out new tasks.

Since its launch in January 2006, the New Horizons spacecraft has traveled over 5 billion miles, passed by the moons of Jupiter, and surveyed the scaley frozen methane ice of its target planet Pluto. In January 2019, it buzzed by Arrokoth, another billion miles beyond Pluto-the most distant object to have ever been visited by a spacecraft. The data it returned from this intact remnant of our Solar System's formation has given us important new insights into how that process happened.

But New Horizons' mission is far from over. While it may never have another close encounter with an orbiting object, the team that operates the spacecraft is working out ways to put its instruments to new uses.