Life After ST3: If It Wins

Where to next? Photo via: Dennis Hamilton

If Sound Transit 3 wins in November, Sound Transit will have its hands full. It will operate Sound Transit 1 ("Sound Move") services, execute the final seven years of Sound Transit 2 construction (including 18 new stations by 2023), and stand up project delivery for Sound Transit 3. This ambitious list of obligations will dominate Sound Transit's attention for years to come. But even $20 billion in ST3 projects (in current dollars) won't exhaust the imagination of activists. As the system expands, connecting to it becomes more valuable, not less.

Under current and proposed tax authority, ST3 consumes the agency's entire fundraising capacity for at least 25 years, and bond repayments will continue for well over a decade after that. Unless there is yet more sentiment for additional legislative authority, this will be it for the working lives of most of the people reading this article.

"The overwhelming focus will be on project delivery," says ST CEO Peter Rogoff, "and there is no room to take a breather." After a win, Rogoff plans to "stand up a team right away" to examine lessons learned from ST 1 and 2, reform processes accordingly, and start hiring staff to support all the new projects.

If there's anything to come that's more exciting than steady execution, it's haggling over the details of each alignment. ST spokesman Geoff Patrick said that ST3 "allows the board to make refinements to the representative alignments," although the legal department believes "it is not legally doable" to build entirely new projects, like Ballard/UW, from tax revenue without additional voter approval. That still leaves plenty of opportunity to find budget space to bury sections of track, serve First Hill, or any one of a series of other improvements that interest groups might organize around.

Mr. Rogoff also noted "there haven't been any board discussions" about what an ST4 might like look like. He couldn't responsibly say much beyond that, but we're free to speculate.

The are no immediate prospects for additional revenue authority. Even though ST3's spine was a part of the original 1990s "Sound Move" vision, it came 8 years after ST2 and 21 years after the first Sound Transit public vote. The further out any action occurs, the harder it is to appreciate public opinion, the economic position of both the region and its component communities, and how transportation habits evolve. But is there anything we can say about what ST4 might be in the aftermath of a Yes vote this November?

The are no immediate prospects for additional revenue authority. Even though ST3's spine was a part of the original 1990s "Sound Move" vision, it came 8 years after ST2 and 21 years after the first Sound Transit public vote. The further out any action occurs, the harder it is to appreciate public opinion, the economic position of both the region and its component communities, and how transportation habits evolve. But is there anything we can say about what ST4 might be in the aftermath of a Yes vote this November?

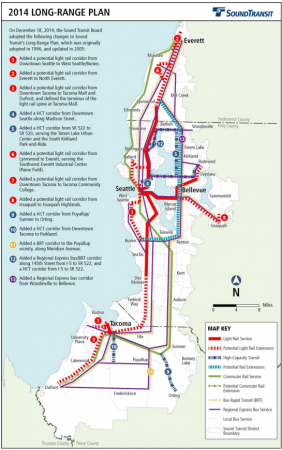

We already have some idea what further projects the subareas want, because they're in the Long Range Plan. The North King subarea's infinite demands likely include, in the next round, a Ballard/UW line and Link to White Center. Together with East King, north-end cities are interested in rail on the SR 522 corridor. East King County would also probably like to extend the Ballard/UW line across 520 and/or finish Link through Kirkland to Totem Lake. South King would probably further enhance Sounder service, and may also invest heavily in a Burien/Renton line. In Snohomish County, the only remaining item is extending Link to Everett Community College. Similarly, Pierce County envisions extending the spine to Tacoma Mall.

The takeaway from these demands is that the subarea math is not at all well-balanced. Given this set of demands, another regional package with subarea equity will be unlikely. There are a few organizational ways out of this box.

The subarea framework has served its purpose in clearly delineating the benefits to each area's voters. Optimistically, once most voters have access to the full ST3 system, they will see the collective gains from projects from which they don't directly benefit. More likely, the unified structure of the Regional Transit Authority would break down, with cities like Seattle petitioning the legislature to tax themselves without raising taxes across the entire RTA. That way Seattle could build Ballard-UW without Orting or Lakewood's assent.

With the spine dream complete, would suburban legislators and other leaders let Seattle chase its dreams?

The opposite reaction is to expand the District. As high-quality transit stretches further out, that will spur further demands in places like Olympia and Marysville. If regional voters view Sound Transit as essential by 2030, the risk of taking on even more sprawling voters may serve a hunger that balances demands in the core. The discussion won't come in December, or 2017, or even 2020, but it will come.