Passenger Rail and Central Washington

Amtrak Charter in the Yakima River Canyon

For all the technical merits of transportation projects, there's nothing like a personal stake in the outcome to elevate your interest level. Recently, STB veterans like us have been pulled towards Central or Southeast Washington for various personal reasons. For Zach, it is the possibility that his partner may be taking a job in Yakima three days a week. For Bruce, it was scouting in the Tri-Cities for a place for his Phoenix-dwelling mother to retire a bit closer to her son.

When it comes to transportation options between Seattle, Yakima, and the Tri-Cities, it's safe to say we have found them wanting. Pasco hosts the region's only Amtrak station, with daily service west to Portland, and east to Spokane and eventually Chicago, on the Empire Builder. Pasco and Yakima haven't seen a direct rail connection to Seattle since October 1981, when the Empire Builder switched to a service pattern which splits trains in Spokane, serving Seattle via Stevens Pass, and Portland via the Columbia Gorge. (Somewhat famously, the Yakima alignment was instrumental in helping stranded motorists in the wake of the Mount St Helens eruption.)

Intercity buses from Seattle are limited to twice-daily Greyhound service and the Bellair Airporter shuttles. By air, Pasco Airport is the fourth-busiest in Washington, following SeaTac, Spokane, and Bellingham; the next busiest, Yakima, has about a sixth of Pasco's traffic and only one destination (Seattle). High base fares on regional flights from Seattle - for example, $97 for the 30-minute flight to Yakima - testify both to robust demand and undersupplied service.

Relative to the rest of interior Washington and the unpopulated expanses of Eastern Oregon, Central/Southeast Washington has a lot of people. After Puget Sound, the Willamette Valley, and Spokane, Yakima and the Tri-Cities are the largest conurbations in the Northwest, with 500,000 people between them. The typical mix of nostalgic railfans and local economic boosters occasionally make noise about restoring rail service, most recently in May:

Economic development, increased tourism, safer passage over the mountains - advocates of train travel have a host of reasons why passenger rail service should be restored to the Yakima Valley after more than 30 years without it.["]

The goal is to someday re-open passenger service from Auburn to Pasco, going over Stampede Pass south of Snoqualmie. Trains would stop along the way in Cle Elum, Ellensburg, Yakima and Toppenish.

This article doesn't appear to have made it to the Seattle blogosphere, but the idea seems worthy of west-side discussion, because as potential customers and likely financiers of such a service, it needs to be as valuable to us as it would be to them. The idea of Central/Southeast Washington rail service has some very serious challenges, but it has some things things in its favor, not least among them that the organizers of the recent meeting managed to get state Senator Curtis King to show up:

"I think it's a relative - I won't call it a long shot, but it's going to take a lot of things to line up to make that happen in the near future["] If it takes you six hours to get over there from Yakima, I don't think a lot of people are going to do it," King said. "It's gotta be timely, it's gotta be efficient, and it's gotta be at a cost that people can afford, so there's lots of challenges."

Those of us who've been around the block a time or two know only too well that getting a transportation project funded has less to do with technical merit, and more to do with which influential politicians you can hook on to your cause; and there's no bigger fish in our sea than the Senate Transportation Committee Chair. So while the idea has even a smidge of oxygen, let's give it a hearing. What would it take to get trains from Seattle to Yakima and Pasco?

The first thing to note is that the Seattle-Pasco corridor is intact and in active freight use, so there would be little right-of-way acquisition or new track construction needed to operate passenger service. Operating speeds are generally adequate except for two critical stretches: Auburn to Easton over Stampede Pass, and the 11-mile squiggle of the Yakima River Canyon. Much of the line is also still jointed rail (rather than continuously welded), and the bumpy ride of jointed rail precludes the use of Talgo-style tilting trains, which could travel faster on curvy mountain grades.

The final timetables from 1981 show a 6-hour travel time from Seattle to Pasco, roughly 50% longer than the 4-hour, 225 mile drive. Shorter trips east of the Yakima River Canyon are more competitive, with Yakima to Pasco at 1 hour, 50 minutes, although it remains to be seen whether a Seattle-oriented service could be made attractive for trips within a mosly suburban and rural area. To stand a chance of competing sucessfully with I-90 for "wet side to dry side" trips, any reintroduction of passenger service over Stampede Pass would need to come with substantial investment in travel time improvements.

The service plans of the Yakima Valley rail boosters seem to extend only to Pasco, but it's worth putting them in the context of current cross-state surface travel. Seattle to Spokane via Pasco would add about 100 miles and 5.5 hours of travel relative to driving I-90, with the 400-mile trip taking 9 hours (44 mph average). The current Empire Builder travels 326 miles to Spokane in 8 hours (41 mph average). Amtrak's current choice of route, which trades almost all potential riders in the Yakima Valley for the speed of the northern Columbia Basin, presumably reflects a compelling business case for prioritizing the trips of interstate tourists.

Despite the challenges, connecting the 1 million people of Yakima, the Tri-Cities, and Spokane to the Puget Sound is a worthy goal, and likely a politically popular one: rural legislators covet access to weathy metro areas. If we could escape both the the overriding demands of Amtrak's long-distance network, and the nostalgia of "restoring service" as an end in itself, what would be the minmum viable cross-state service?

Let's start with some basic assumptions. The service should run between Seattle and Spokane. It should be state funded, unbeholden to the schedules of Amtrak's long-distance network. The train should offer daylight service, run seven days per week, require minimal right-of-way acquisition, and be serviced at the Seattle maintenance facility. Capital funds should go primarily into the cost of rolling stock, double tracking, and smoothing curves.

If successfully reintroduced within these parameters, this line would be extremely valuable, plugging the primary gap in intercity transit service in Washington, meaning that every metro area of more than 200,000 in Washington and Oregon would have daily rail service, with good onward bus connections at most major stations (see sample service map below).

Map by Zach

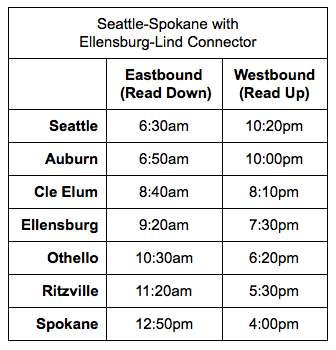

WSDOT studied East-West service in 2001, concluding that Talgo-style trains combined with track improvements could yield a Seattle-Pasco-Spokane travel time of 7 hours, 20 minutes (55 mph avg). Thinking more boldly, a 2007 report by the Washington State Transportation Commission described another project that could do wonders for speeding Spokane service: the Ellensburg-Lind Connector. The Stampede Pass Line converges with the old Milwaukee Road (now John Wayne Trail) in Ellensburg, heads south through Yakima and Pasco, and crosses the Milwaukee Road right of way again in Lind, WA, a few miles west of Ritzville (see map at the top of this post). Re-tracking and rehabilitating that right-of-way for passenger service, on one of the least-used portions of the John Wayne Trail, could cut 2 hours off of Seattle-Spokane service and offer a direct freight connection between Joint Base Lewis McChord and the army's Yakima Training Center. The likely capital costs would be in the $500m range.

Given these difficult but surmountable realities, here are two sample timetables that would be possible with moderate track upgrades, same-day turnaround service, a single trainset, and overnight maintenance in Seattle.

Whatever the ultimate outcome, we think that the million people of Yakima, the Tri-Cities, and Spokane deserve an integrated ground transportation network that connects them both to Seattle and to each other.