Should Small Cities Grow Faster?

Downtown Snoqualmie

For over a year, regional planners have wrestled over growth plans with six small cities that are planning to 'grow too fast'. Last month, the PSRC Executive Board tabled a decision on reclassification that could have eased the way for faster growth in Covington and Bonney Lake.

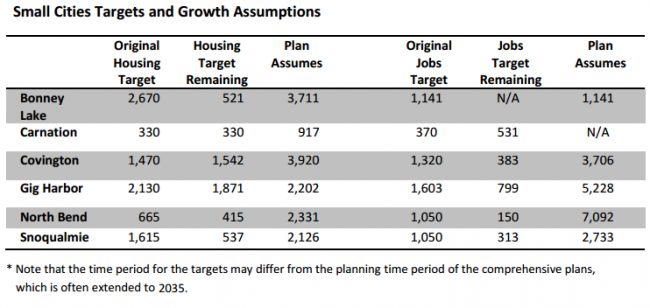

Six smaller cities, four of them in King County, are planning for growth that runs ahead of regional targets.

The region's growth management strategy, VISION 2040, focuses most development within an urban growth boundary. Inside the growth boundary, the highest planned growth in each county is in "Metropolitan Cities" like Seattle and Bellevue. The next highest growth rates are planned for "Core Cities", with progressively lower growth in "Larger Cities" and "Small Cities". Small cities outside the contiguous urban area should grow more slowly than cities within.

In the last round of comprehensive plans, Six small cities created plans with growth capacity well above their regional targets. Four of these (Carnation, Snoqualmie, North Bend and Covington) are in King County, and two are in Pierce (Gig Harbor and Bonney Lake). In response, their plans were certified conditionally until they could come into compliance with regional goals. To date, the conditional certification has not impacted their access to grant funding, but might do so in the future.

Small cities have lower growth targets because they are typically further from major business centers. This means longer commutes that increase demands on regional transportation infrastructure. Unplanned growth impacts traffic in neighboring communities and on rural roads. The character of small towns is to be preserved. (Some small cities are indeed charming, others maybe less so). But slow growth strains the budgets of many smaller towns, dependent on an influx of new residents or businesses to fund existing services and infrastructure.

Two cities with conditional certification, Covington and Bonney Lake, sought reclassification as 'larger cities'. The reclassification might allow a higher growth target (it's not automatic, but switching to a peer group with higher targets would influence future discussions). In December, the PSRC Executive Board appeared poised to approve. Within King County, the debate turned more contentious. The County's Growth Management Planning Council (GMPC) has so far not agreed to a reclassification. Covington meets the size criteria (as does Bonney Lake in Pierce County). But reclassification were not scheduled to happen before the next comprehensive plan cycle. To some, a premature reclassification evades proper consideration of the policy question.

Advocates of faster growth frame the issue as being about autonomy in city decision-making, and claim the PSRC is overstepping its authority. Everybody accepts that cities must plan for enough growth, and growth targets therefore act as a floor on zoned capacity. Do they also act as a ceiling constraining too fast growth in the wrong places? Some of the cities are targeting a pace of development dramatically faster than regional plans. The shared goal of concentrating growth in the largest cities doesn't work if a growth target is only a floor.

Advocates of faster growth frame the issue as being about autonomy in city decision-making, and claim the PSRC is overstepping its authority. Everybody accepts that cities must plan for enough growth, and growth targets therefore act as a floor on zoned capacity. Do they also act as a ceiling constraining too fast growth in the wrong places? Some of the cities are targeting a pace of development dramatically faster than regional plans. The shared goal of concentrating growth in the largest cities doesn't work if a growth target is only a floor.

Bringing the plans into compliance means restricting growth. Some of the options are problematic. North Bend, for instance, has reduced housing capacity by buying up otherwise commercially zoned land for parks, reducing permanently the footprint of the city. But North Bend has also progressively down-zoned undeveloped residential zones in the city from 6-8 units per acre to just 2 units per acre. Slowing growth may mean swapping denser growth for sprawl.

Bringing the plans into compliance means restricting growth. Some of the options are problematic. North Bend, for instance, has reduced housing capacity by buying up otherwise commercially zoned land for parks, reducing permanently the footprint of the city. But North Bend has also progressively down-zoned undeveloped residential zones in the city from 6-8 units per acre to just 2 units per acre. Slowing growth may mean swapping denser growth for sprawl.

Small city mayors, supported by the construction lobby, are poetical about the appeal of small city life. Notice, however, that median house prices in Covington ($334K) and Bonney Lake ($343K) are up to 60% lower than Seattle and Bellevue. The market is signalling that many people would prefer to live in denser places with shorter commutes. Growth in distant small cities is propelled by the scarcity of housing closer to major employment centers.

Workers who move to exurban cities accept long commutes for homes they can afford and impose disproportionate traffic impacts on others. Fewer than 2% of workers who live in Covington are employed there, and two-thirds are commuting more than 10 miles each way to work. Eventually, growth in Covington and other exurban cities will translate to new highway projects and perhaps another cycle of sprawl.

In a way, the small cities are forcing a discussion about affordability and the pace of housing growth. Housing becomes even less affordable if growth is curtailed in small cities without a corresponding easing of barriers to growth in high-demand areas. Are the inner suburbs prepared to grow faster so that workers don't have to drive so far for a home they can afford?