Seattle-Vancouver High Speed Rail Part 3: Bellingham to Vancouver

[Readers have been asking about our 4-part series on Seattle-Vancouver high speed rail. With Zach moving on to new adventures, we've asked Alon Levy of the excellent blog Pedestrian Observations to finish out the series. Enjoy part 3 below. - Ed.]

Seattle Transit Blog has looked at special challenges involved in high-speed rail in the Pacific Northwest, between Seattle and Vancouver. I briefly explained the problem a few years ago, and earlier this year, Zach Shaner here began a series examining the Seattle-Vancouver corridor segment by segment. Part 1 dealt with the Seattle-Everett slog, and part 2 with Everett-Bellingham, an easier but already less slow segment. In this post, I will look at Bellingham-Vancouver.

The Bellingham-Vancouver segment has four important decisions:

- How to go around Bellingham?

- How to get between Bellingham and the built-up area of Vancouver, roughly around Surrey?

- How to complete the last 20-25 miles into Vancouver?

- Where should the Vancouver terminal be?

Decision #4 is the subject of part 4. In this post I'd like to examine the first three decisions.

BellinghamIt is impossible to serve Bellingham's CBD. The legacy alignment through the city has a curve of radius 920 feet (53 mph) and grade crossings; it also has poor connections to I-5 from the south. The only reason to use this alignment is if there are plans to never run trains that skip the city. Whatcom County's population is 200,000; HSR would pass through Burnaby (population 230,000) and Surrey (s520,000) without stopping. Letting express trains skip Bellingham is fine, even desirable.

Instead, trains should run alongside I-5, and serve Bellingham at an outlying location-see map below. The best locations are a lot closer to the CBD than the current Amshack in Fairhaven. There is still a problem: I-5 is not especially straight through Bellingham. On the map, potential stations are in black, and curve radii (in meters) are in blue:

HSR alignment through Bellingham

The tightest curve on the I-5 right-of-way has radius 600 meters, or 2,000 feet, good for 78 mph. It and the curve to its south can be eased to about 3,600 feet, good for 105 mph, before they turn into an S-curve. A 105 mph slowdown for 225 mph express trains is bad, but not fatal-about 95 seconds; the 2,000 meter (6,600"^2) curves farther north are good for 140 mph and add another 15 seconds of slowdown.

Across the borderNorth of the built-up area of Bellingham, I-5 runs through open land. The terrain is very flat on the American side of the border, and there is so little development that the best alignment is an area rather than a line. In other words, instead of drawing a single line between Bellingham and Langley or Surrey, it's better to draw a western limit and an eastern limit, and between them pick the alignment that presents the easiest construction in terms of minor cut-and-fill, overall distance, and land acquisition.

Metro VancouverTo understand how trains should enter Metro Vancouver, it is useful to understand where in Vancouver they could end up. There are two reasonable options for a Vancouver station: Canadian Pacific's Waterfront terminal (where the West Coast Express goes), and Canadian National's Pacific Central (where the Cascades go). Waterfront is in the CBD, Pacific Central just outside it, two stops out on SkyTrain's Expo Line. A new station location at Commercial/Broadway, at the intersection of the Expo and Millennium Lines, could in theory work, but in practice the tracks are constrained and there is no room for platforms.

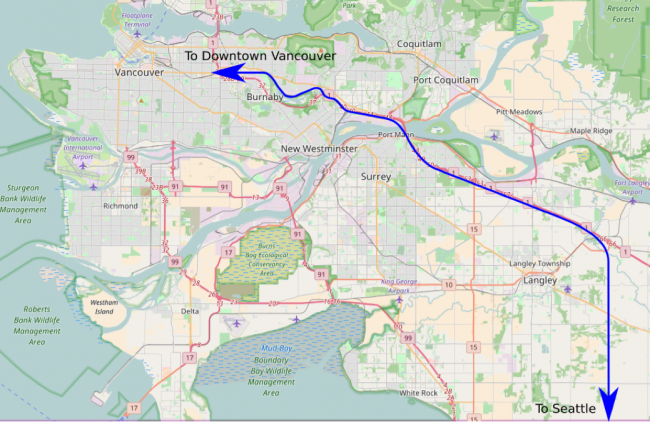

Regardless of where trains go in Vancouver, the only useful way out is on the CN track; the CP track feeding Waterfront is too curvy and constrained. Today, the Cascades reach the CN track via the BNSF track, which winds its way between the Surrey built-up area and Burns Bog Delta Nature Preserve. Passenger trains have to go through New Westminster Rail Bridge, a single-track structure with 46 freight trains per day and capacity for just 14 more trains. There is no chance of HSR without replacing or bypassing this bottleneck. Here is an alternative alignment:

Fortunately, there is a good right-of-way letting trains enter the CN track from the east: the Trans-Canada Highway, a full freeway. It is dead straight through Langley and Surrey, and mostly undeveloped on its south side; it also has a usable median most of the way. South of the Fraser, only two miles pose a real problem, between Guildford and Fraser Heights: there, development goes right up until the right-of-way, which requires some combination of viaducts, takings, noise abatement measures, and speed compromises in the 150 mph area. This is low hundreds of millions of dollars, not billions.

The Fraser crossing would be a new bridge. The New West Rail Bridge replacement is budgeted at $110 million. The nearby two-track SkyBridge, connecting SkyTrain to Surrey, was built in the late 1980s at a cost of $28 million, about $50 million in today's money. The Trans-Canada crosses the Fraser at a somewhat wider point than SkyBridge, but still, costs much higher than $100 million are unlikely. Then it's industrial takings, possibly straying from the road to ease a curve (the road itself is 2,500 feet at the bridge, good for 88 mph). The final approach on the CN line may require widening the line from two to three tracks, and possibly some grade-separations, but there's room for all of this, and Canadian construction costs are lower than American ones.

ConclusionThe Bellingham-Vancouver segment looks scary, and Vancouver has a dearth of high-quality rail alignments. But it is actually not that bad-Bellingham imposes some slowdowns, but the road from there to Metro Vancouver is clear, and within Vancouver, not a single meter of tunnel is necessary except perhaps in the immediate downtown area. On the longest option, going to Waterfront Terminal, this is 60 miles of rail, in about 28 minutes one-way for trains not stopping at Bellingham. While slower than most recent HSR lines, this requires just routine construction in greenfield areas and some urban viaducts, and possibly minor tunneling near Downtown Vancouver; this should be doable for a low single-digit number of billions of dollars. The problems for Seattle-Vancouver HSR are more at the Seattle end than the Vancouver end.

Part 1: Seattle to Everett

Part 2: Everett to Bellingham

Part 3: Bellingham to Vancouver

Part 4: The Inland/Suburban Option