The business case for high speed rail

High speed trains in Tokyo (Image credit: Flickr/tokyoform)

High speed trains in Tokyo (Image credit: Flickr/tokyoform)In 2017, WSDOT published a feasibility study of high-speed rail (HSR) in the Vancouver-Seattle-Portland corridor. It estimated a $25-42 billion capital cost for a rail line that would carry about 5,000 riders a day in 2035 and would just cover operation costs by sometime in the 2040s. This hardly appeared promising, but was enough to prompt a trickle of funds from the Legislature and regional partners for a "business case" study.

We have obtained a copy of the business case study which WSDOT will send to the Legislature this month. How does it advance our knowledge beyond what we learned in 2017?

In broad terms, the financial outlook for high-speed rail inthis study looks a lot like the numbers presented two years ago. The businesscase doesn't attempt to revisit the capital cost estimates of the earlier study.Ridership is somewhat better, but break-even on operating costs remainssomewhere in the 2040s.

Ridership

Ridership is revised upwards vs the predictions of the FRA'smodel. Whereas the earlier study predicted 1.7 - 2.1 million annual riders in2035 on the core Vancouver-Portland corridor, the more current study raisesthat to 1.7 - 3.1 million by 2040 (average 8,500 per day for the upper estimate).The 2040 date assumes construction is complete by 2034 and ridership hasfinished its 'ramp-up' window. Anticipated fare revenue per passenger, at 52cents per mile (2019 $), is unchanged.

The ridership estimates are, peculiarly, based on a voluntary survey that was promoted by HSR advocates. Despite the skewed sample, the analysis is close to the earlier estimates for express travel between the three major cities. The higher best-case results improve on those estimates by assuming up to nine stops, greatly increasing the number of possible trip pairs.

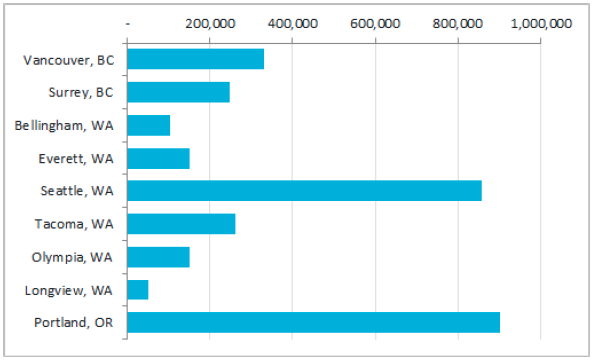

The business case predicts high-speed rail will capture12-20% of the in-scope travel market. The in-scope travel market are those journeyswithin the Cascadia corridor that might reasonably be taken by regional rail.Most journeys are more local, and some are longer distance. The addressablemarket is estimated at 10.7 million annual one-way trips today, rising to 14.7million annual trips by 2040.

High speed rail could capture 12-20% of the in-scope travel market from autos, air, and other rail. These are the mode shifts in the highest ridership Scenario 1D (image: WSDOT/WSP; click to enlarge)

High speed rail could capture 12-20% of the in-scope travel market from autos, air, and other rail. These are the mode shifts in the highest ridership Scenario 1D (image: WSDOT/WSP; click to enlarge)To place that regional trip demand in perspective, it's about one-fifth of person trips through Seatac. This validates an observation from the earlier feasibility study. While HSR captures a healthy mode share in its market, it doesn't overcome how there isn't very much travel between the major Cascadia cities.

In the highest ridership scenario, a fifth of high-speedrail ridership is from the assumed elimination of air travel that is entirelywithin the corridor (4% of in-scope travel in the baseline). However, airtravel on connecting flights is hardly affected (16% of baseline). Anotherfifth of high-speed rail ridership is cannibalization of slower conventionalrail services. The balance (up to 12% of the market) is taken from auto travel betweenthe cities.

Service Model

Three service models are highlighted, though several othersare reviewed in the study. All anticipate 220 miles per hour design criteria.

Alternative service scenarios with a mix of base and express service (image source: WSDOT/WSP; click to enlarge)

Alternative service scenarios with a mix of base and express service (image source: WSDOT/WSP; click to enlarge)"Scenario 1C" illustrates a three-stop alignment with 21trains running express between Vancouver, Seattle and Portland. Travel timeswould be 48 minutes to Vancouver, or 58 minutes to Portland.

"Scenario 2A" is an eight-stop alignment with a base andexpress service. Major Puget Sound stations are at Bellevue and Tukwila. Nineexpress trains per day serve the major stops, with 12 base trains also servingother stops. Travel times on local service are about 30% longer than theexpress trains.

"Scenario 1D" is a nine-stop alignment with a base and express service. Service levels are the same as Scenario 2A, but the Puget Sound area station is in Seattle.

In the highest ridership scenario, Portland and Seattle would each contribute about 2500 boardings per day (image: WSDOT/WSP; click to enlarge)

In the highest ridership scenario, Portland and Seattle would each contribute about 2500 boardings per day (image: WSDOT/WSP; click to enlarge) Paying for HSR

Building high-speed rail would be an enormous capital cost. Thestudy attempts to place this in context of other costly alternatives, arguingthat high-speed rail looks better when benchmarked against major highway expansionsor new airport construction. Perhaps high-speed rail could pre-empt theestimated $108 billion cost of adding a lane on I-5 across the state, or buildingan additional runway which could exceed $10 billion.

The problem with this argument, of course, is that HSR ridershipis almost immaterial to whether we make those alternative investments. The reduceddemand for air travel, across all regional airports, is far less than 1% ofexpected traffic at Seatac alone. HSR will hardly affect even the timing offuture airport investments, let alone whether those investments are necessary.

Neither is anybody proposing a general widening of I-5 to address travel between the major cities. In the rural areas, it's generally uncongested. In the urban areas, the overwhelming majority of auto trips are shorter distance, and the fraction of longer distance auto trips that would be diverted to rail is a rounding error on overall demand at any point that is congested.

This year, the Legislature approved $225,000 for another study if Microsoft, Oregon, and British Columbia would kick in the balance of the $895,000 cost. This was a 94% reduction from Governor Inslee's budget request. Meanwhile, WSDOT is updating their Long Range Plan for more incremental improves to Cascades service. Legislators seem content to fund more studies, but not the several orders of magnitude higher cost of building HSR. The debate over the future of intercity rail in the northwest is likely to continue inconclusively for some time.