The latest generation of climate models is running hotter—here’s why

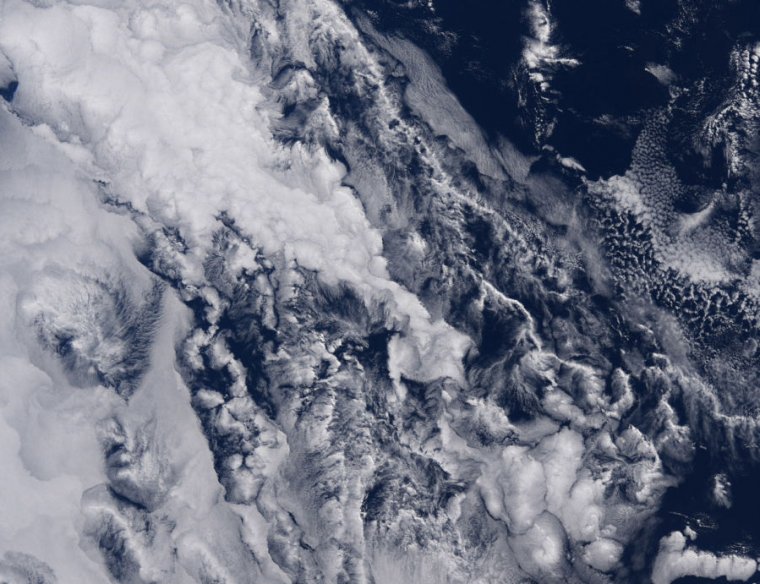

Enlarge / IDL TIFF file (credit: NASA)

Ahead of every Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, the world's climate modeling centers produce a central database of standardized simulations. Over the past year, an interesting trend has become apparent in the most recent round of this effort: the latest and greatest versions of these models are, on average, more sensitive to CO2, warming more in response to it than previous iterations. So what's behind that behavior, and what does it tell us about the real world?

Climate sensitivity is one of the most-discussed numbers in climate science. Its most common formulation is the amount of warming that occurs when the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere is doubled and the planet gets a century or two to come to a new equilibrium. It's an easy way to get a sense of what our emissions are likely to end up doing.

In climate models, this number is not chosen in advance; it emerges from all the physics and chemistry in the model. That means that as modeled processes are updated to improve their realism, the overall climate sensitivity of the model can change. As results have trickled in from the latest generation of models, their average climate sensitivity has noticeably increased. A new study led by Mark Zelinka of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory analyzes these new model simulations, comparing their behavior to the previous generation.

Read 10 remaining paragraphs | Comments