The COVID-19 misinformation crisis is just beginning, but there is hope

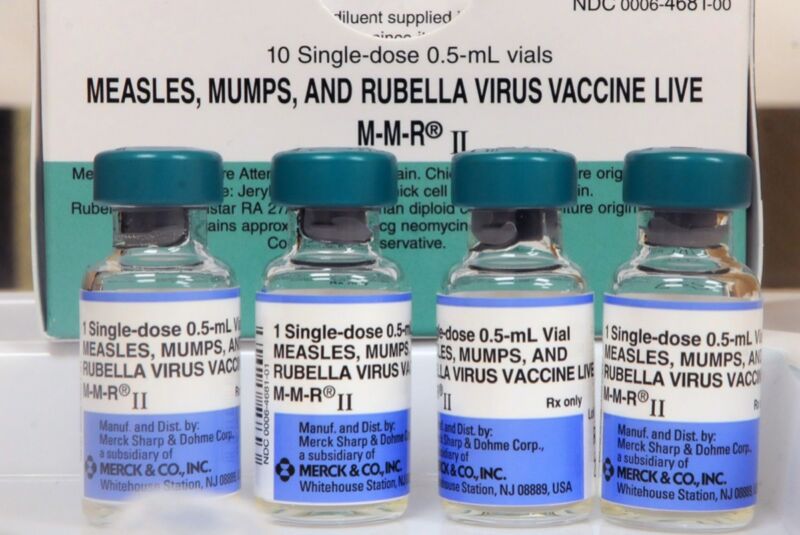

Enlarge / Vials of measles vaccine at the Orange County Health Department on May 6, 2019 in Orlando, Florida. (credit: Paul Hennessy/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Last year, the United States reported the greatest number of measles cases since 1992. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were 1,282 individual cases of measles in 31 states in 2019, and the majority were among people who were not vaccinated against measles. It was yet another example of how the proliferation of anti-vaccine messaging has put public health at risk, and the COVID-19 pandemic is only intensifying the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories.

But there may be hope: researchers have developed a "map" of how distrust in health expertise spreads through social networks, according to a new paper published in the journal Nature. Such a map could help public health advocates better target their messaging efforts.

Neil Johnson is a physicist at George Washington University, where he heads the Complexity and Data Science initiative, specializing in combining "cross-disciplinary fundamental research with data science to attack complex real-world problems." For instance, last year, the initiative published a study in Nature mapping how clusters of hate groups interconnect to spread narratives and attract new recruits. They found that the key to the resilience of online hate is that the networks spread across multiple social media platforms, countries, and languages.

Read 18 remaining paragraphs | Comments