How the Warsaw Ghetto beat back typhus during World War II

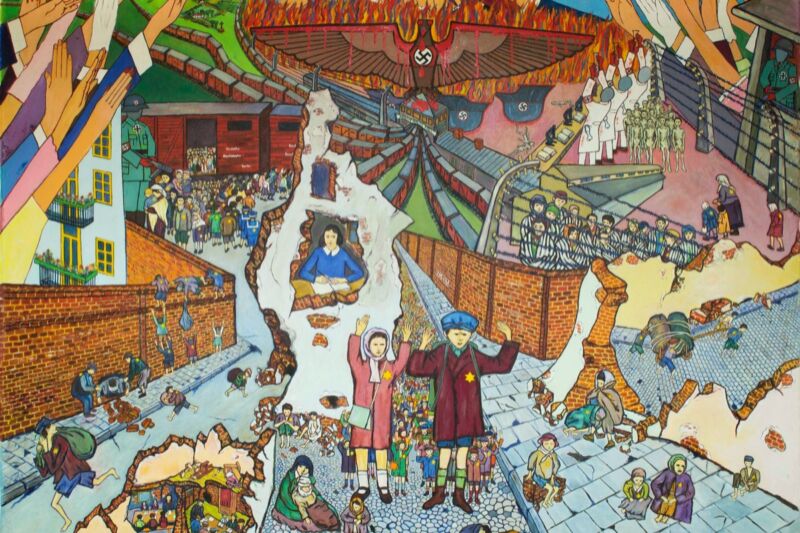

Enlarge / Painting by Israel Bernbaum depicting Jewish children in Warsaw Ghetto and in the death camps (1981). (credit: Monclair State University collection)

During the Nazi occupation of Poland during World War II, Jewish residents in Warsaw were forcibly confined to a district known as the Warsaw Ghetto. The crowded, unsanitary conditions and meager food rations predictably led to a deadly outbreak of typhus fever in 1941. But the outbreak mysteriously halted before winter arrived, rather than becoming more virulent with the colder weather. According to a recent paper in the journal Science Advances, it was measures put into place by the ghetto doctors and Jewish council members that curbed the spread of typhus: specifically, social distancing, self-isolation, public lectures, and the establishment of an underground university to train medical students.

Typhus (aka "jail fever" or "gaol fever") has been around for centuries. These days, outbreaks are relatively rare, limited to regions with bad sanitary conditions and densely packed populations-prisons and ghettos, for instance-since the epidemic variety is spread by body lice. (Technically, typhus is a group of related infectious diseases.) But they do occur: there was an outbreak among the Los Angeles homeless population in 2018-2019.

Those who contract typhus experience a sudden fever and accompanying flu-like symptoms, followed five to nine days later by a rash that gradually spreads over the body. If left untreated with antibiotics, the patient begins to show signs of meningoencephalitis (infection of the brain)-sensitivity to light, seizures, and delirium, for instance-before slipping into a coma and, often, dying. There is no vaccine against typhus, even today. It's usually prevented by limiting human exposure to the disease vectors (lice) by improving the conditions in which outbreaks can flourish.

Read 16 remaining paragraphs | Comments