A physicist studied Ben Franklin’s clever tricks to foil currency counterfeiters

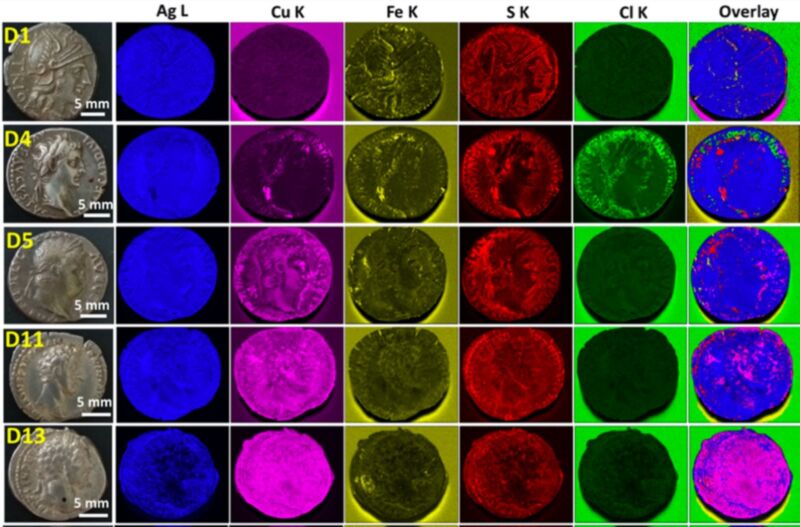

Enlarge / Nuclear physicists used micro-XRF scanning to produce elemental maps for Roman denarii coins and their color overlays. (credit: K.V. Manukyan et al., 2019)

Most people associate nuclear physics with the atomic bomb or nuclear power plants, and those associations are often negative. Michael Wiescher, a nuclear physicist at the University of Notre Dame, wants to change that perception by applying his expertise-and some of his sophisticated imaging hardware-to research that bridges science, history, and culture. His work in this area has included collaborations to analyze a rare medieval manuscript and unearth currency fraud and forgery throughout history, most notably in ancient Rome and Colonial America. He recently described those efforts at a virtual meeting of the American Physical Society's Division of Nuclear Physics.

Much of this work was conducted in conjunction with undergraduate students in physics, chemistry, art restoration, history, and anthropology as part of a course Wiescher teaches at Notre Dame on physics-based methods and techniques in art and archaeology. In the process, students can get certified as operators of a broad range of advanced physics-based instruments and techniques. These include Raman spectrometers, transmission electron microscopes (TEM), a 3MV tandem accelerator, handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanners, micro-XRF scanners, and X-ray diffractometers, among others.

The course covers such topics as nondestructive analysis of the paintings of Vermeer and the Archimedes palimpsest; tracking the inks used by medieval scribes for illuminated manuscripts; whether the Vinland map is real or a forgery (it was recently conclusively shown to be fake); using studies of the Shroud of Turin to discuss uncertainties in carbon dating; and reviewing how Luis Alvarez once used cosmic rays to search for hidden chambers in Egyptian pyramids in the 1960s.

Read 13 remaining paragraphs | Comments