Spinning black holes may prefer to lean in sync

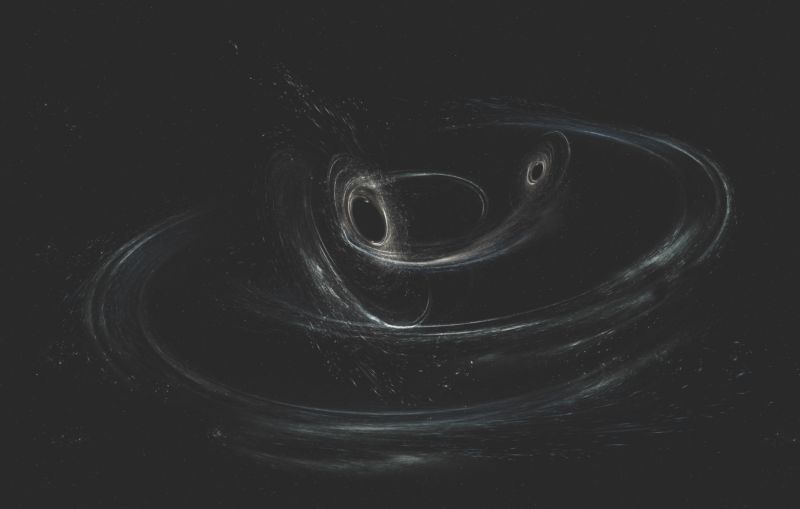

Enlarge / A simulation of a black hole merger. (credit: LIGO/Caltech/MIT/Sonoma State (Aurore Simonnet))

I was pretty excited when LIGO, the giant double-eared gravitational wave observatory in the US, detected the first gravitational waves. When Virgo came online, triangulating gravitational wave signals became possible, and gravitational wave astronomy became a reality.

Once the initial excitement of seeing individual events died away, it was only a matter of time and statistics before scientists started pulling new insights out of the data. A pair of new papers has looked at black hole merger statistics, and the papers' results suggest that there might be something unusual in the distribution of black hole spins.

The revealing death spiralGravitational waves are the result of mass moving through space and time. The mass stretches space and time, causing a ripple effect, much like the bow wave from a boat moving through water. And, just like a bow wave, the heavier and faster the mass, the bigger the wave. Unlike water, space-time is very stiff, so it needs more than an ocean liner to create a noticeable gravitational wave.

Read 15 remaining paragraphs | Comments